We are reproducing another past article by the late MK Binodini, translated from the original Manipuri by Pradip Phanjoubam. Though the title may suggest otherwise, this article is not at all an attempt at writing history or putting its record straight. As a matter of fact, the author is not too much bothered about following or being faithful to the historical and chronological order in her narrative. On the other hand, her account is more in the nature of a walk down Memory Lane in which historical events flow out of the nebulous mist of time and memory, following an unpredictable psychological order as in the literary tradition of “the stream of consciousness.” Her portrait of U Triot Sing is hence a personal vision of a historical event, and its narrative follows the commands of her heart, rather than the academic rigours of disciplined objectivity and linear study of facts and figures. But very often, the heart tells the truth better and more faithfully than does the head.

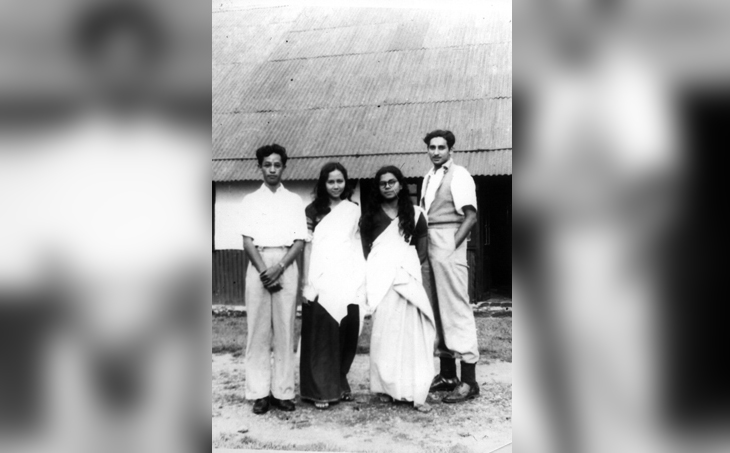

It was one of those long, dreary afternoons. I was alone in the house, enjoying the leisure, or boredom if you please, of having nothing to do, measuring out the minutes and hours by the coffee cups, waiting …. waiting absolutely for nothing. It was one of those rare moments in time when the mind is actually a blank with absolutely nothing weighing it down. I was not paying attention to anything so I did not notice who dropped my afternoon newspaper, The Telegraph, Guwahati edition, on my portico. When I came across it, absent-mindedly I picked it up and still without any focus began browsing through the pages. It was July 28, and a feature on U Tirot Sing caught my attention momentarily, before I drifted into that region of the mind where it is simply a milky nothingness. A bell rang somewhere, somewhere in the deep recess of my unconsciousness. With a start, I came around. U Tirot Sing I said. Of course I know who U Triot Sing is, and with an intent that surprised me, I returned to the article on him. It was a tribute to the Khasi leader on the occasion of his 168th death anniversary. Almost instantaneously, the mist dissappeared from my head and for the first time that afternoon, I knew what I was upto. With close attention I read and re-read the article. I leaned back on my easy chair after I was satisfied I did not miss any point and this time consciously I re-entered my mind and began a trip down Memory Lane. Before I even realised it, I was already lost in a reverie. It was such a long time ago. I was so young and full of vim and thirst to explore the world around me. I was a lass of 18, studying at the St Mary’s College, Shillong. Michievious days, I should add. I remember how Khukhu and I used to be such thick friends. Her name is Anjali Lahiri, nee Anjali Das, but we used to know her affectionately as Khukhu. What fun it used to be, bunking class to enjoy the afternoon sun, chatting endlessly and tirelessly and eating local eateries at the shop near our college.

It was Khukhu who first told me about U Triot Sing during a picnic to Cherrapunji 60 km away from Shillong with her family. She was already married at that young age. Khukhu is a domicile of Shillong although not native to the place. She speaks Khasi like her own mother tongue and knows about the legends, myths and customs of the place as much as any Khasi. On the way I remember she had pointed out to me the hill ranges where the Khasi leader had once tried to organise and unite the disparate Khasi chieftians of the time to oppose the British who had already eyed the Khasi and Jantia hills to set up their administrative base. The Telegraph article wrote: “U Tirot Sing and his general, Mon Bhut. had tried to prevent the British from constructing a road from the Khasi Hills to Sylhet. Tirot Sing was arrested by the British in 1833 and jailed in Dhaka where he remained till his death… What startled me was Khukhu told me the British employed the service of two Manipuri princes to subdue and capture U Tirot Sing. I distinctly remember how unbelieving I was when she said this and when she finally managed to convince me that this really was the case, I remember I flushed in shame. How could my forefathers do such a thing as oppose somebody else’s aspiration for freedom? Haven’t they tasted the agony of losing their own freedom at the hands of the Burmese during the Chahi Taret Khuntakpa? After the paroxism of inherited guilt and shame passed by, my curiosity wondered back to the Khasi freedom fighter again. Why don’t you write about him? I remember telling Khukhu. I also remember her answer: “I am not a writer?” I had at the time thought I should one day research on this legendary Khasi leader and write about him, but never got around to do it. How fortunate we in Manipur are, I had also thought at the time. If Tirot Sing was a Manipuri, I can imagine how his exploits would be sung and immortalised in our oral epic tradition of Khongjom Parba, eulogised in Royal Chronicles, enacted in many Shumang Lilas, stage shows, dance dramas…. Even in defeat he would have been a hero and a martyr. He would at least not have been a mystical figure fading from the public consciousness as he was until recent times when there is a visible wave of revivalistic efforts amongst the Khasis. I quote The Telegraph article again: “..Students should be educated on the way Tirot Sing led the challenge to save the traditional institutions like the Nongkhlaw Syiemship…. A number of parents too expressed desire to teach their children about the legendary and historical figures of the state…. ‘ I do not want my son to spend the day swimming or watching television… I want him to learn from Tirot Sing.'”

(contd next week)

We reached our picnic spot. It was a lofty mountain and we passed through may Khasi villages. There was a huge rock nearby and Khukhu and I decided to climb it and have a better appreciation of the grounds on which U Tirot Sing fought his valiant battles. Mr Lahiri decided the path was too steep for him and stayed back at the base and so Khukhu, her children and I were left to accomplish the mission on our own. We did it not with too much difficulty. The sight was breath-taking and soon U Tirot Sing, or the princes of Manipur, receded to the back of the mind. We were above the coulds physically and spiritually. As we watched the clouds sail by underneath us, I remember Khukhu and I singing Rabindra Sangeet to our hearts delight not caring who was listening. Khukhu told me there is a Khasi myth that tells of this place as the birthplace of rain. The thought made the place even more enchanting to me. After a time, at some distance, I noticed Khukhu intently looking for something in the grass. I was curious and was quickly by her side. “What are you playing? What are you upto?” I asked mischieviously. Khukhu giggled and I discovered that she had just lost her four brand new false front teeth. Amidst uncontrollable fits of laughters I joined the hunt, but all in vain. At last, fatigued from laughter, and seeing little hope of recovering the lost dentures, we decided to descend to the spot where Mr Lahiri was waiting for our return with a long face – famished. Mr Lahiri, a lawyer by profession, is a gentleman alright, but I could notice he also gets impatient, although good-heartedly, with the pranks Khukhu and I often are up to. He scolded us for taking so long and after he was through with his feined bout of irritation, invited us to join the picnic lunch of rice and chicken curry. Khukhu and I were still not able to control fully the waves of laughter rising from within and this irritated Mr Lahiri some more. We finally collected our lunch plates and went away some distance were we ate between laughing fits. Khukhu could hardly manage a chicken piece at the end of our lunch. We also ultimately told Mr Lahiri about Khukhu’s misfortune, and earned some more scoldings from him. In Shillong a fresh four front teeth for Khukhu were ordered and while it was being readied, like true bosom friends, ready to stand by each other come what may, I too stayed away from class.

When I first heard about Tirot Sing from my friend Khuku, in my college days, I was so fascinated by the romance of the war the Khasi leader fought. A David versus Goliath match, but one in which David fought a heroic battle but lost. A brave heart born in the wilds of the lofty, rugged mountains of the Khasi and Jantia hills, fiercely independent, loyal lover and a patriot to the core. I could then imagine him as the archetypal romantic warrior, chivalrous and fearless as any champion of justice can be. I had at the time next to made up my mind that I would research into the annals of this hero and write about him. But life is unpredictable. Here I am in the evening of my life, ruminating on what seems like another life ages ago. I walked a different path at one of the many crucial crossroads of life, distancing me further and further away from that college days intent, until Tirot Sing relegated into that region of my mind where consciousness seldom touches. Then came the article in The Telegraph that reactivated the memory of the great man.

I apologise that I have no intimate knowledge of Khasi history but after The Telegraph article, I did do some limited research on the unhappy association of the Tirot Sing period of Khasi history with that of Manipur. I must admit I could not have done it without the liberal help I got from my friends. It was not so much my obsession for a hero of my youth, but the shared guilt of how my forefathers got involved in soiling one of the most enlightening moments of Khasi history.

Treaty obligation. That was what made the Manipur princes fight for the British to subdue the resistance put up by U Tirot Sing and his Khasi army to the British design to build a road to Sylhet from Assam through the Khasi hills, and obviously to ultimately bring the Khasi hills under its total control. I quote a passage from S.L.Barua’s Comprehensive History of Assam : “… But it was Teerot Sing, the Siem or Raja of Nongkhlao, who led the actual war of liberation. He had been persuaded by David Scott to place himself under the British protection and agree to opening up of a road across hills joining Assam with Sylhet. When the road was cleared and a bungalow and a police outpost were erected at Nongkhlao, doubts arose in the minds of freedom loving Khasis that it was just the beginning of more wanton agression on the hills. On April 4, 1829, a band of about 500 Khasis under the leadership of Teerot Singh attacked and massacred two English officers – lieutenant Burton and Bedingsfield, besides sixty Indian Sepoys at Nongkhlao. They also burnt down the bungalow and released the convicts employed in the construction of the road. ….”

What was then the treaty obligation that prompted the Manipur princes to fight for the British. Thanks to the tradition of keeping a Royal Chronicle (Cheitharol Kumbaba) in the Manipur court, the event is well documented. As in all such chronicles however, this one too sings the glory of the king involved. The two princes are none other than Maharaja Gambhir Singh and Maharaja Nara Singh and their Khasi expedition is entered in the Royal Chronicle. The writing of this chapter was commissioned during the reign of Maharaj Chandrakriti, the son of Maharaj Gambhir Singh who succeeded him, and he had hired the service of a writer of the time by the name of Chingakham Chaobaton Singh.

Subsequently, a book in verses, titled “Khahi Ngamba” was adapted from this chapter of the Royal Chronicle chronicle by another writer called Chandra Singh Moirengthamcha, with the intent of, in his own words, the benefit of posterity.

According to the chronicle, the expedition began in saka 1751 on the fourth day of the Manipuri lunar month of Sajibu, Monday. The British army and the Manipur army after meeting at Sylhet, went up the Khasi hills separately from different directions combing the hills village by village. The Manipur army met with success and encountered Tirot Sing’s force and captured him in battle. He was duly handed over to the British and Gambhir Singh and his troops promptly returned to Manipur.

It was not a war between the Manipuris and the Khasis, then. The British, were desperately looking for an answer to Tirot Sing’s guerilla war in the difficult terrain of the Khasi hills and they approached their ally in Manipur for help. Gambhir Singh and Nara Singh were obliged to the British for their help in their own war for the liberation of their land from the Burmese during what historians describe now as Manipur’s own holocaust, Chahi Taret Khuntakpa. This period of history tells us that the Burmese in a major campaign ran over the Manipur and Ahom kingdoms and savagely plundered them. As a matter of fact, historians say the end of the once powerful Ahom kingdom was marked by the Burmese invasion. Both the Ahom and Manipur sought the British help. Gambhir Singh and Nara Singh were raising an army in exile in Cachar at the time to fight back the Burmese. The British obliged, partly out of the need to control the rising regional power that the Burmese were at the time and partly because of their own interest in the territory that the Burmese then controlled. The British army stationed in Sylhet drove back the Burmese from Ahom territory but in the case of Manipur the two princes wanted not the English troops to enter Manipur but only military hardware. They got that and in the bargain the British got themselves a useful ally whose service they reaped to the fullest in their campaigns against the Khasis as well as the Angamis.

That was probably the first major confluence of Manipur’s history with that of the Khasi hills. But it definitely was not the last. After the British have established their rule in practically all of the northeast region, and Shillong became the administrative hub of the British Assam province, my father Maharaj Sir Churachand, bought a beautiful cottage in Upper Shillong called “Rose Cottage.” I was told in my infancy I was often taken there during my father’s trips to Shillong on business as well as holidays. I have little memory of the place as I was only an infant but my Nanny often told me enchanting stories about the house and how I disappeared one day to the alarm of everybody, only to find me inside a rose bush.

Sir Churachand then bought another estate with a beautiful house in the heart of Shillong called Englishbee. The house was subsequently taken over by the British administration from the Manipur king’s possession and in its place he was given the Redlands which incidentally is still in the possession of the Manipur government. Englishbee, is today the estate over which stands the Meghalays Assembly building.

There was another curious connection my family had (or has) with the Khasi hills. When we were very young an Englishman often used to be our guest in Shillong. Much later in life I was told the man was Sanajaoba McClough and is the great grandson of Maharaja Gambhir Singh. One of Gambhir Singh’s grandsons married the daughter of an Englishman with long association with Manipur and his Meitei wife, and out of that wedlock was born Sanajaoba. In my college days, after I learnt of this bit of my family history, I tried to trace my uncle Sanajaoba. I was told that he had married a Khasi and was living in penury somewhere in Upper Shillong. Obviously after learning I was looking for him, a brief letter arrived from him one day saying he desires anonymity now.