It should not surprise anybody that prolonged insurgencies leave behind scars, some barely visible but nonetheless excruciating. The case of the civil militia Village Defence Force, VDF, in Manipur, raised in 2008 after an assault at a village by an insurgent group is one particularly poignant. That was a period marked by uncertainty and chaos in the state, when insurgency was at one of its peaks, and practically every morning newspaper headlines screamed of gory gun violence, unrest over alleged fake encounters or else the continuance of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, AFSPA.

The fateful incident happened during the Yaoshang (Holi) festival celebrated for five days and marked by sporting events and revelries of the Thabal Chongba (moonlight dance) late into the nights. On March 24, at a Thabal Chongba at Heirok village about 35 km from Imphal, an insurgent organisation which later confessed they were out to eliminate a party offender in the crowd, opened fire killing three and injuring several more. Enraged villagers went on a warpath and decide to ban all insurgent activists and sympathisers from their village. They also pleaded with the government to arm them.

After some initial hesitations, the government decided to take advantage of the situation and give the idea of a civil militia a try and the first batch of VDF took birth at Heirok with an initial 300 recruits. But the initiative soon spread to villages across the state with youth lining up to join, not always out of vengeful anger against insurgents, but in the hope this would ultimately land them a respectable job, a consequence predictable in a state with high youth unemployment, where only government jobs are considered a job. Today there are 10,050 of these men though officially only 1,500 are listed.

These young men were recruited under no established recruitment rules or service guarantee, and were just village volunteers armed by the government demi officially. They were paid Rs. 1,500 initially but this later was raised to Rs. 3,000 and now the stipend stands at Rs.8,500. When the VDF came into being, in Chhattisgarh, a similar initiative, Salwa Judum, was drawing flakes and in 2011 declared illegal and unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. In Manipur the VDF prevailed, probably because nobody challenged its legality, but also because the government benefitted from their service.

They soon became a handy force, put to service as any police constabulary but paid much less. Their assignments range from static guard duties at vital installations, road opening duties during public unrests, sentry duties for lesser VIPs etc., with no holidays or off days. Their service contract is for a year at a time, but almost as a norm routinely extended for all these years. This was expected for insurgency in the state, though now in a lull, is far from resolved. Moreover after 13 years of engaging them, it has become a humanitarian issue to simply let go of them when they have already passed the age to seek fresh employment. Trapped in a job that has no certainty of lasting out their careers or has scope for promotion, signs of unrest are becoming evident and some have even begun leaning to petty crimes as conduits in drugs trafficking, bootlegging etc.

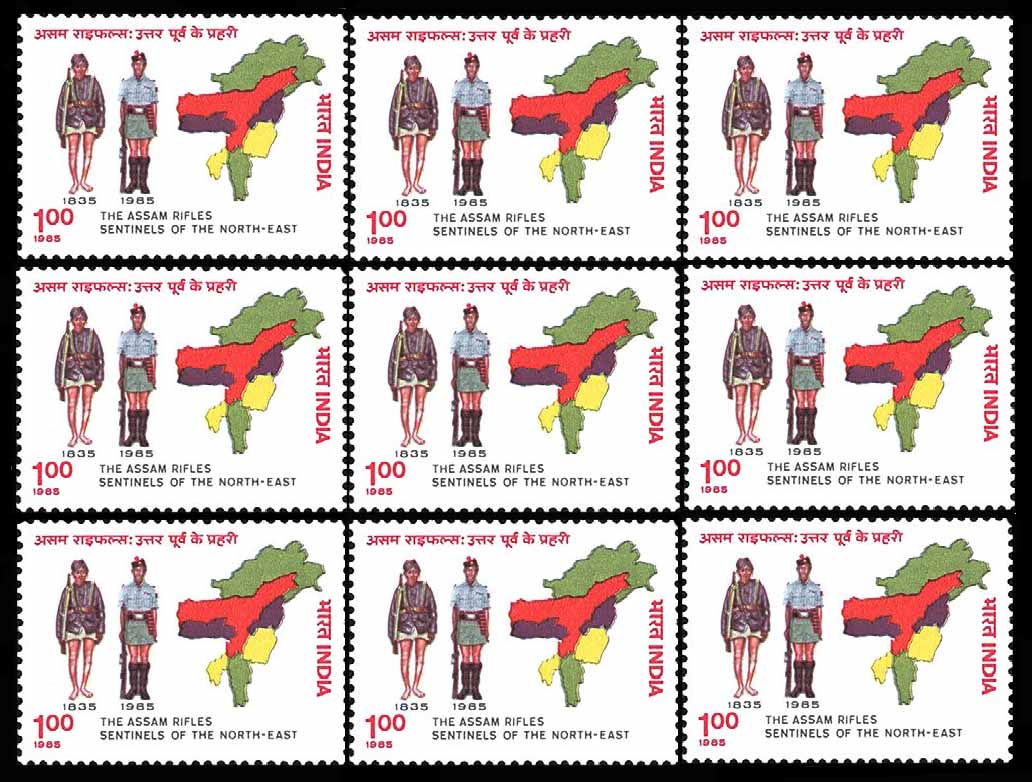

Perhaps the Northeast’s colonial history has a lesson here. After the British established their administration in Assam in 1826, they began withdrawing their army from the region feeling it was no longer cost effective. But by 1835 they again found the need for a little more security than the police could provide. Civil officer E.R. Grange came up with the idea of raising the Cachar Levy, a civil militia officered by the police initially but later by the military. This militia ultimately became India’s first paramilitary force, the Assam Rifles.

L.W. Shakespear in History of Assam Rifles, describes the Cachar Levy as a force “less paid than the military, but better armed than the police”. To motivate the personnel, each of the five original unit of this force was attached to a Gurkha Rifles formation, and the promise was those who performed well would be absorbed into the army formation they were affiliated to. Indeed, this militia, which came to be the Assam Military Police, became a fertile nursery for the Gurkha Rifles, so much so that during the WW-I, it became drained of all experienced personnel as they were supplying troopers to the GR at the rate of 200 a month till the end of 1917 to fight in Europe. This, Shakespear notes, was one of the reasons why the force took longer than expected in putting down the Kuki Rebellion. In recognition, immediately after WWI, this militia was officially recognized as a paramilitary force and christened Assam Rifles.

Could this history of the Cachar Levy have a lesson for the Manipur government in resolving its VDF dilemma? Could there be a mechanism to have them gradually absorbed into different related government services according to performance and calibre?

First published in The Telegraph Read Here