By Murthy Chavali, Alliance University, India in Bengaluru, India

There is no escape from them as they are in the air we breathe and in the everyday products we use.

When you wake up in the morning, wash your face, apply a skin lotion, take a drink of water, clean your teeth and step outside for a walk near the beach your body is most likely ingesting microplastics the entire time, through your mouth, your nose and your skin.

There is no escape.

It’s bad enough that we ingest microplastics in our food and water. But they also —literally — get under our skin. Microplastics have been reported in consumer products such as face creams, face washes and various other cosmetic products.

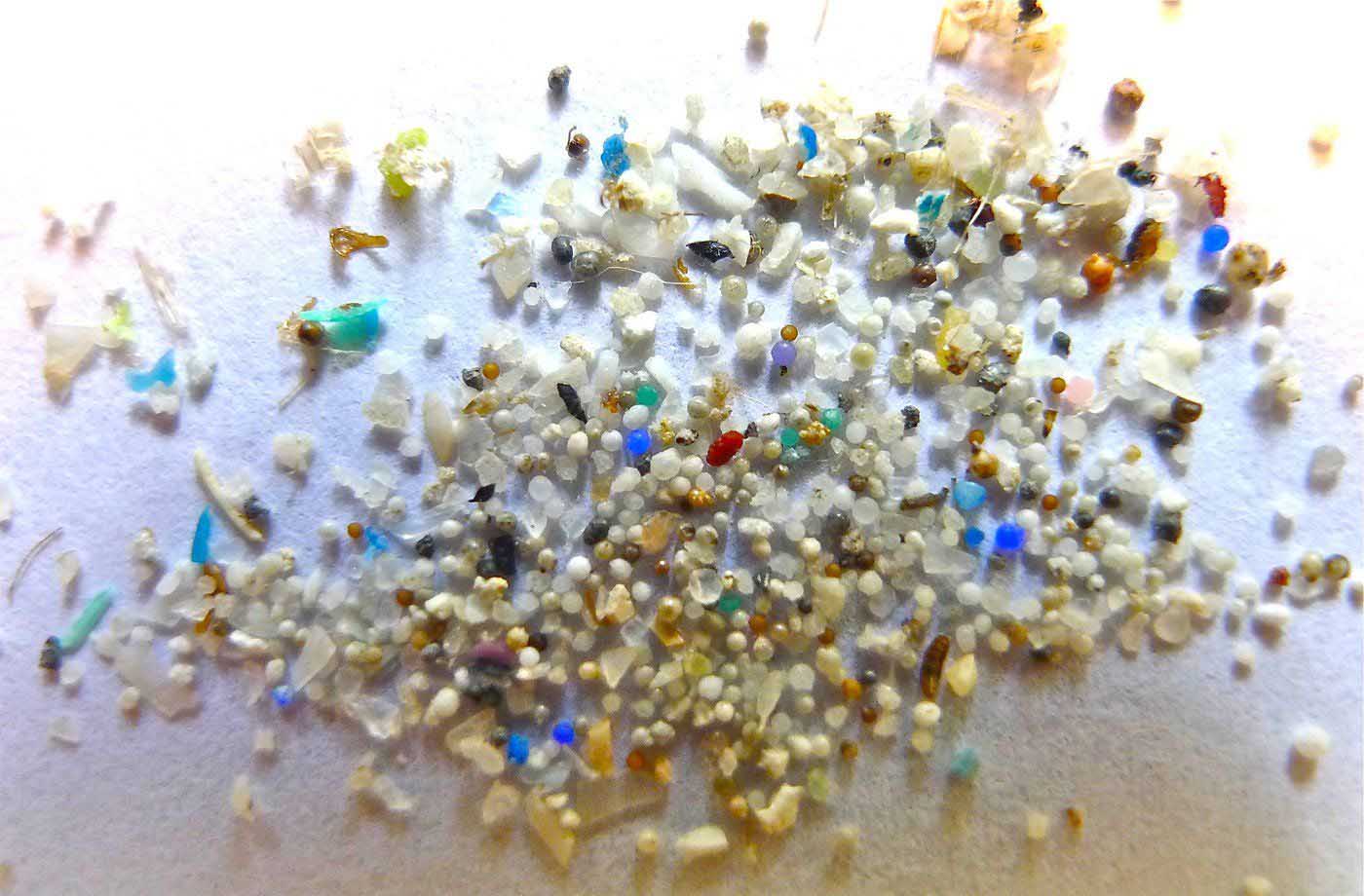

They are often in the form of small microbeads which are widely used in health and beauty products.

These minute particles – less than 5mm – carry a wide range of chemicals, the most common being polyethylene, which has been associated with serious health outcomes including cancer, heart disease and poor foetal development.

Studies show that microplastics from cosmetics and toothpaste may be absorbed by the skin which could lead to cell damage on the skin’s outer surface (the epidermis). Researchers are investigating whether these plastic particles can penetrate the deeper layers of our skin.

Microplastic absorption through the skin and the possible detrimental effects of extensive skin contact with plastic particles (e.g., from dust, microbeads and liquid hand cleansers) are now a focus for investigators.

We also breathe in many microplastics. As they accumulate in the respiratory system, they could potentially cross into the brain via the bloodstream. Microplastic particles have been discovered in human lung tissue. The chemical composition of these particles may cause acute and chronic respiratory problems.

While microplastics can be inhaled, the bulk of them are ejected by the self-clearing mechanism of our airways. Still, some may linger in the lungs, triggering a localised response, including inflammation, particularly in those with compromised respiratory systems.

This study showed that microplastic concentrations in indoor air were up to 28 times higher compared to outdoor environments, highlighting the need for stricter precautions in homes and offices. Microplastics in the atmosphere come from various sources including synthetic textiles and everyday polyvinyl chloride (PVC) products around us.

Stepping out for fresh air isn’t necessarily a means of escape. Sea breeze and sea spray can also be a consistent source of microplastics in the air. One study estimated about 136,000 tons of microplastics are emitted from marine waters to the atmosphere as sea spray annually.

These particles are easily transported to nearby areas. For example, an air mass trajectory study revealed microplastics can travel as far as 95km through the atmosphere.

Microscopic particles of solid or liquid matter suspended in the air often contain these microplastics which in turn carry toxic chemicals such as polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

But there is not yet sufficient information about the fate and risk of airborne microplastics in the air around us.

With evidence of the increased consumption of single-use plastics, notably, face masks during the Covid-19 pandemic, it is critical to push and invest in more detailed research on the impact of microplastics on our health.

While plastics have gained immense popularity in modern life since the mid-1950s, the resulting plastic waste and mismanagement in disposal have caused ecological problems. Plastic abandoned in the environment is prone to breaking down, leading to the generation of microplastics and nanoplastics which reached marine and animal life and subsequently humans.

To examine the accumulation of these toxic particles in humans through the food chain in diverse regions requires careful planning and coordination involving ecologists, pathologists, and epidemiologists.

Reliable exposure data is also essential for risk assessment and management. Policymakers could start now to implement plastic waste reduction policies at the national and international levels.

Prof Dr Murthy Chavali is Dean (Research), Department of Science, Faculty of Science & Technology, Alliance University, Bengaluru, India. He declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.