What is history and memory, therefore, the nation/community made of? The past is constantly reconfigured in search of an identity in the present. It has become a site of contestation for different groups. Past is a creation of the present and the creation of it is incomplete without a figure around which that past can be woven.

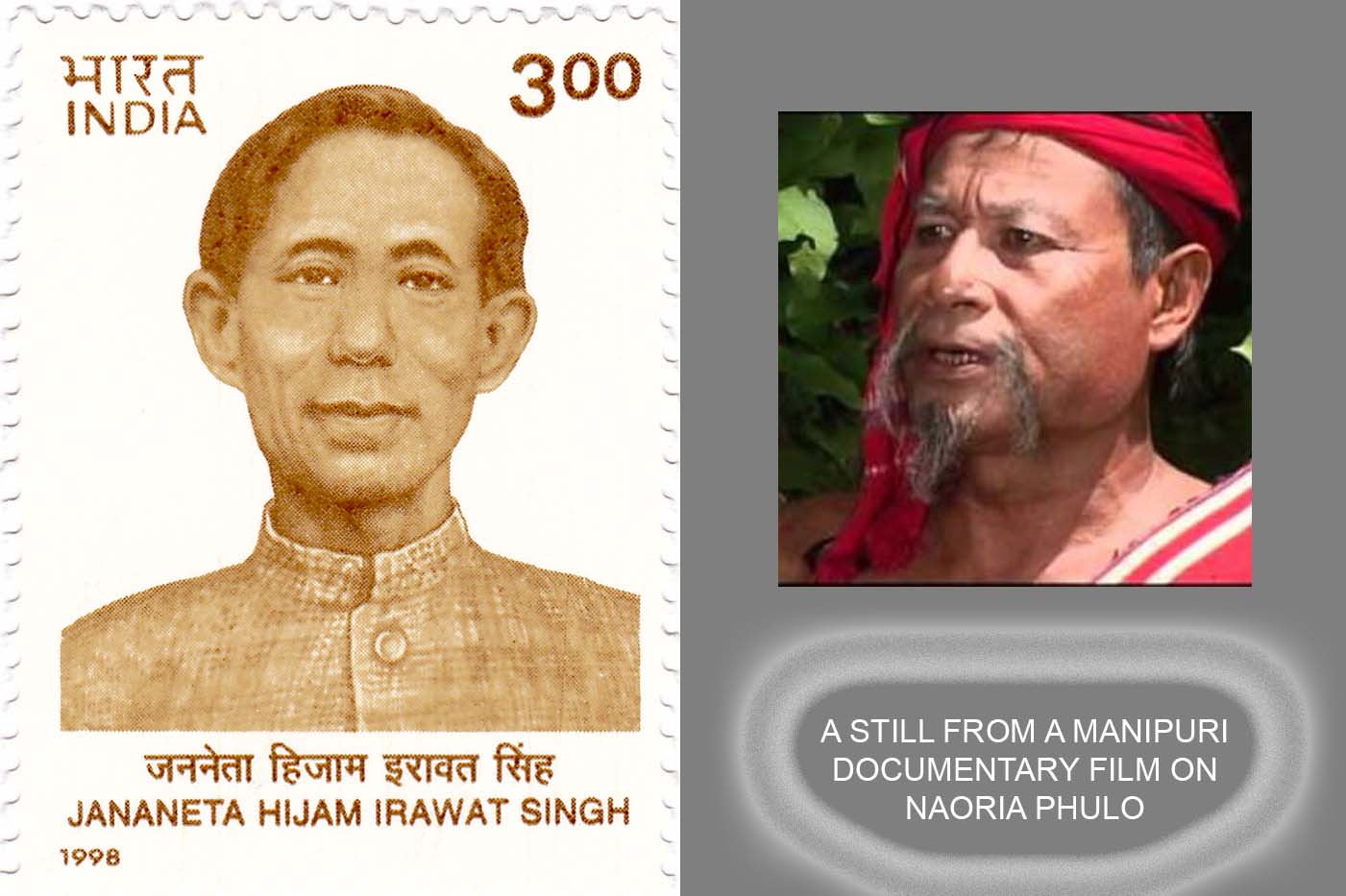

The article concerns two prominent figures of Meetei and Manipur –Naoria Phulo and Hijam Irabot. The present history of Manipur particularly that of the Meetei, is woven around the figure of Hijam Irabot. He was a revolutionary and a Marxist of the first half of the twentieth century. He was also a martyr, a sport enthusiast, an author, and a social reformist who led the Nupi Laal, making him a perfect figure around which a modern Meetei identity/community was easy to conceive. Irabot is remembered and memorialised by both the people and the state. Phulo, on the other hand, is unknown; his works are unread and his contributions under recognised. The essay seeks to understand why Irabot is venerated while Phulo is known little to none in our collective memory.

1

At present, Phulo is regarded as a mere religious cult figure that is remembered only by his followers. At the most, he is remembered as a person who initiated Meetei religious movement. He is not remembered as a person who brought in the question of modernity, emancipation, history writing, script and language. His work, Eigi Wareng, is unknown and oblivious to many. Reading his works should make us think of a possible philosophical engagement with other societies and cultures which are seeking emancipation. When his contemporaries from Imphal valley were singing Sankritana, he realised that Sankritana was one reason why Meeteis were lagging behind in education and scientific temper. While his contemporaries were begging for a Meetei future which rested in Sanatan Gouradharma, or, seeking Sanskrit as a source language if Meeteilon became insufficient for expression. He broke away claiming that Meetei should stop using Byakaran to understand Meeteilon. Phulo propagated that Meeteilon can only be studied using the grammar of Wahouron, and not the Indic Byakaran. The implication is that as long as Meeteilon is judged as per the principle of Byakaran, it will remain an insufficient language. Phulo’s rejection of Byakaran is a self-assertion of Meetei identity, thereby, questioning the very criteria of terming something/someone as insufficient. It is a rejection of a rejection. At the cusp of the formation of modern Meetei identity, he presented a radical shift and turn over.

Phulo also spoke against the exploitation of Meeteis by the Hindu religion/Brahmin, importance of education and science in order to emancipate the Meeteis. In the 1930s and towards the end of his life, Phulo believed in the project of history making through which Meetei can fight the false history and narrative authored mostly by the mayangs. He was clear that only when the Meeteis begin to write their own history, the narrative of the Meeteis as descendants of Arjuna can be rectified.

Phulo proclaimed Hinduism responsible for the social, moral, economic debilitation of the Meeteis. He said: “Gouriya dharmana Meeteigi fagadaba pumnamak sumthi saana saidatlabani”(Gouriya religion [Hinduism] has destroyed everything that is good for Meetei completely). A figure, who spoke against religious superstition of Hinduism, and initiated Meetei into modern/ity question, is now seen with indifference. Why is Phulo reduced to a mere cult figure? How do we understand such a reduction of Phulo into a cult? Why are his works not easily available? Why is the present generation unaware of him and his contributions?

2

Memories are made constantly. There are official and unofficial memories. Official memory is constituted and protected by the state while unofficial memory is constituted in the minds of the public. Museum is an excellent site to understand the official memory and the desire of a community to keep that memory alive. While writing on the elision of tribal from the state and public memory of the state in his article, Jankhomang Guite assumes an absence of Hijam Irabot in the official imagination/memory of the state which he argues is because he was a communist. However, considering the recent wave of Irabot day celebration by both the public and the state, this assumed absence remains in question. Not only his statue stands tall in front of Manipur University Library, but September 30 is also now a state holiday. The day is observed in remembrance of his sacrifice and contributions made in the Manipuri society. Guite, nevertheless, argues that the memory of Irabot was preserved by his people (unofficial memory) and thus contributed in the elevation of Irabot from unofficial to official memory of the state.

Induction of Irabot in the state/official memory, and the public which kept his memory alive, is a manifestation of the mode that functions between the state and its people. The fact that Irabot stands irreconcilable with the Indian state and the appropriation of the former by the later requires a different study altogether. However, I would like to put forward, that the induction of Irabot is possible because the keeper of his memory shares a common ideological and religious ground with the state. On the other hand, the keepers of Phulo’s memory is still a minority and a visible gap lies between the state and the public memory of Phulo.

Irabot’s outlook was limited to reforming Hinduism and he expressed promotion of a reformed Hinduism instead of uprooting it. His association with Nikhil (Hindu) Manipur Mahasabha (later as Mahasabha) and the resolutions taken in the meetings of the sabha is worth pondering over. In the first session of the Mahasabha (1934), apart from other resolutions, the session resolved to set up a historical society to be led by the notorious Atombapu Sharma. In the second session (1936, Silchar), Gouradharma Pracharini Sabha was established and Manipur Bijoy Panchalli was set ready for publication. The book was a Hinduised re-telling of Meetei history which characterised the Atombapu School. In the third session of the Sabha held in Mandalay (1937), he is alleged to have declared “If we do not preserve the essence of Sanaton Gouradharma, our country will one day be gone like an insignificant bubble in the vast ocean.” He was critical of orthodox Meetei Brahmins, but was supportive of the Gouradharma Prachini Sabha, a new Hindu organisation founded by the liberal Brahmin, Lalita Madhop Sharma. The new group initiated reformative measures for the preservation of Hinduism.

Irabot’s ambivalent position on Hinduism at the threshold of Meetei religious revivalism, helped in instituting a hegemonic social norm that allowed the exclusionary Brahminical ideology to proliferate. We have seen from history that most liberals work with benevolence with the subject to form a hegemonic control of the later.

3

The content and contour of nationalism is largely determined by the characteristics and behaviour of its leading class and the one which emerges as the ‘nationalist class’ creates the ‘national-popular’ depending on their ideology and politics. Any challenge to this ‘national-popular’ is met with contempt and vilification. This uncanny relationship between the ‘national-popular’ and nationalist elite hinders what could possibly be a ‘national popular.’ There is a surreptitious hijack of the many by a few elite.

Between Phulo and Irabot, what becomes apparent is while Irabot received the support of the Meetei nationalist elite, Phulo remained a ‘crazy old fellow’ who has no support besides his sparse but dedicated followers. Although, resistance to Hinduism was marked political change, production and dissemination of a reformed Hinduism as consumable and staple Meetei ‘national-popular’, in some way or the other, persisted the long twentieth century. The nationalism that was created protected Hinduism under the guise of preserving and reviving Meetei identity.

Phulo’s movement, both religious and emancipatory pedagogy, rejected Hinduism in Silchar and Imphal valley around the time when Irabot and other literary figures were harking on reforming it. Founding of Apokpa Marup and Meetei Marup in Imphal in the first half of the twentieth century was a moment of Meetei emancipation. When he was ostracised in 1931, Phulo said “Houjikti leibaktagi figei sengjarabanina, ibungosing pumnamaksu mapu ibungogi mariida leppa matang youramalle haina ningjei. Leppabudi machingeidagi leppiri. Machingeida leppado leibakna khangdaba –chasingda yaodaba haibadu tuk thok-ee.” (Now we are free from the Hindu society, the time has come for us to stand for our God. You have stood for our God since a long time. However, it is different now. Earlier, we had stood for our god in hiding, away from the Hindu society). This quote is significant because, for Phulo, that moment of ostracization was a moment of emancipatory potential, a moment of freedom, a freedom which they were all fearful of. It was also a moment of clarity and separation from the Hindu society. He also said that before this moment, they were hiding behind a deceptive mask of being a Hindu. Now, they do not have to hide their identity and the works they do. They can absolutely devote themselves to their god.

4

What wrong did Phulo do that he continues to be insignificant and his contribution ignored? This is a bigger question that the present Meetei society needs to answer after an honest soul searching? Perhaps, what is required, at a time when imitation has become a political exercise and truth in Manipur, is the need to read Phulo and take his spirit.The instituted process and the constituted politics of systematic elision of Phulo was, thus, the means whereby the dominant class and community achieved legitimacy and visibility and appropriated even the claim to history of a whole community.

In our conversation of the present, Phulo should be brought in. His positions and ideas should be made part of the social engineering of the present. My effort is an attempt along this line of thought, to make Irabot and Phulo talk to each other. Only in this talk, we could see our past differently and understand our present better with more nuance.

When nationalist elites continue to ignore Phulo and venerate Irabot, this question should haunt us. Why is Phulo reduced to a mere religious figure? Why emancipatory tools such as education, science, history are unaware to many? In whose benefit Phulo is ignored? Answer could perhaps lie in our inability to give way to ‘authentic’ Meetei in an effort to hold on to its adversary.

The author teaches at MECI Explorer Academy, Imphal. His research interest includes language and script debate, minority studies, literary theory. The article is extracted and reworked from his Ph.D. dissertation submitted to University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad. He can be reached at [email protected]