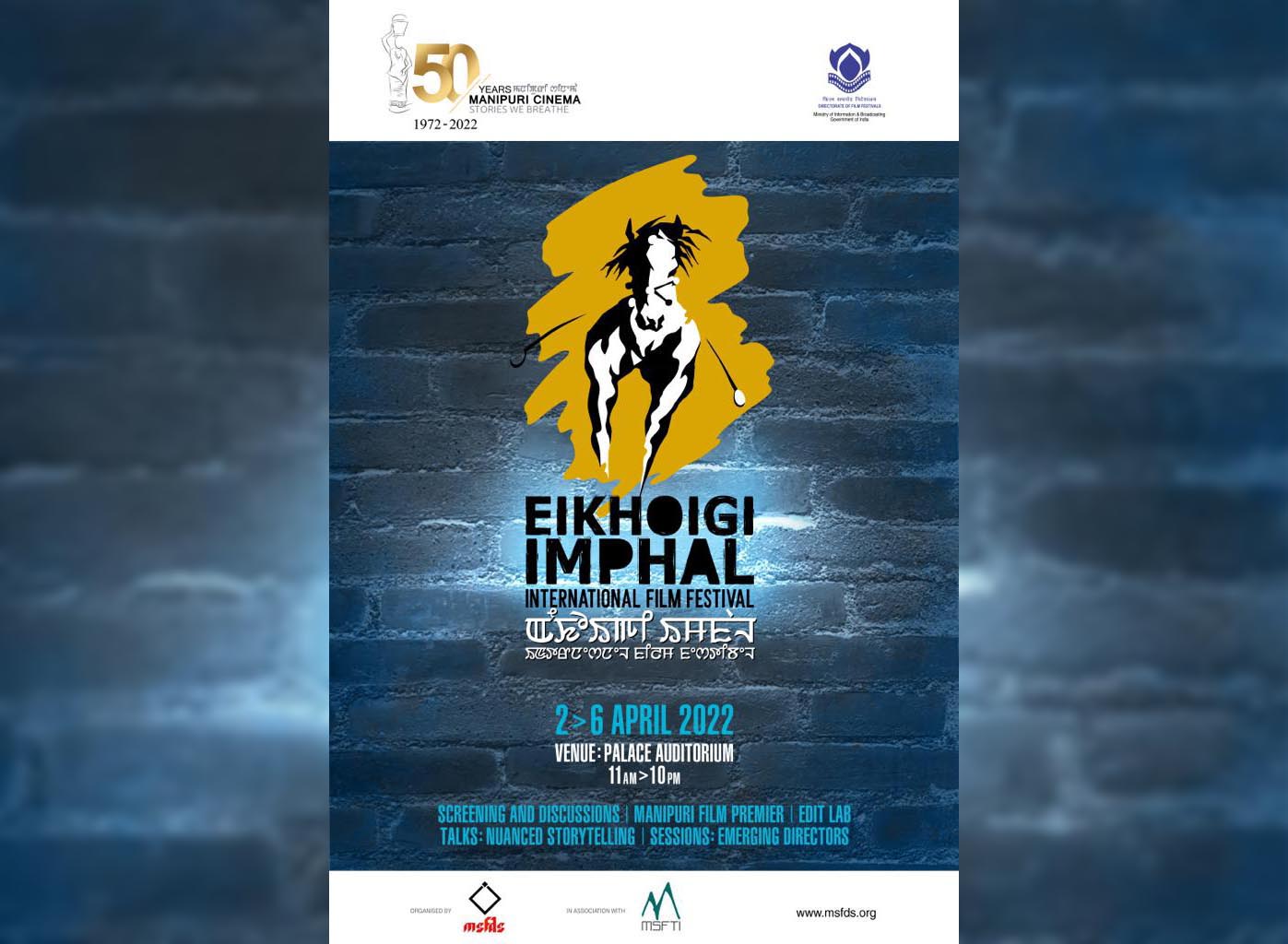

The 14th Manipur State Film Award function, preceded by an impressive international film festival under the banner “Eikhoigi Imphal” (Apil 2-6), was successfully held in a well-attended function at the Palace Auditorium on April 9, the day Manipuri cinema completed 50 years since it formally came to being. The films in competition this year were as usual in two categories, “Features” and “Non-Features”. I was one of the three jury members for the “Non-Features” section, the other two being noted film maker Ningthouja Lancha who was the chairman of this jury team, and noted dramatist, Loitongbam Dorendro.

There were only four entries in this section, which is not very encouraging for it does indicate there are not too many filmmakers attracted to this genre and of film making. But from what were indeed on offer, it can be said the field ahead is open and can be promising, although I do hope there will be more directors willing to take on the onerous challenges of non-fiction cinematic story telling. Below are some of my impressions on the four films in competition this year, and how and why one among them, Ayekapashingee Pukkei was considered worthy of the best film award in this category. Incorporated into this assessment are also the impressions of my two other jury colleagues.

Ayekapashingee Pukkei

Very straight simple and linear narrative, but a story well told with clarity. The subject is the progress of the art of painting in Manipur. It has a brief sketch of the genesis of this art form from premodern times in Manipur, when artists began exploring the use of available colours derived mostly from plants and vegetables, till a greater spectrum of chemically derived colours became available via import from the world outside of Manipur. The film then traces the progress of this art from in the modern era, and the influences of the trends and styles of modern European painting, flowing in from other states of India whose initiation and familiarisation to the Western world was earlier. The film has no pretensions of narrative or ideological sophistication, but it is refreshingly informative and articulate. The cinematography and photo composition are pleasing in very ordinary ways too, adding immense value to the overall story telling.

Pabung Syam

This is a documentary which could have easily come out on top with a little more work. It is a biographical sketch of a pioneer of Manipuri films therefore amounts virtually to a revisit of the history of the film enterprise in Manipur. However, the formidable hurdle the film was somewhat unsuccessful in overcoming has to do with the fact that the person portrayed is a living legend of Manipuri cinema. Aribam Syam Sharma, is a multi-faceted character – a singer and composure of repute, a dramatist, a film maker of renown, an actor and more. The film does give glimpses of these diverse interests of Syam Sharma, fondly Pabung Syam to many, and also lists his many admirable achievements, but as a biography it remained somewhat incomplete for the missing portrayal of the artistic and political milieu the great filmmaker grew up in, for nothing happens in a vacuum. What was Syam Sharma’s childhood like, what and who were the greatest influences on him, what were his dreams and ambitions before fame came his way, what were his moments of triumphs and heartbreaks, his fears and optimism etc. Questions like, were there parallel movements, rivals, project partners etc., who in their own different ways complemented his progress, are left largely unanswered.

Bloody Phanek

This is film which looked promising at the start. The title, and indeed the introductory scenes of the film did suggest this was going to be a radical exploration and denunciation of patriarchy’s oppressive character in the Meitei society. Phanek is the traditional lower body wrap-around garment of women popular across South East Asia and beyond, and amongst the conservative sections in many of these communities, including the Meiteis, it is treated as unclean and polluted, therefore an object of bad luck which menfolk must avoid touching. However, this powerful subject is allowed to shed its sting as a fight against an obvious symbol of gender oppression. Instead, the film becomes a collection of opinions on the matter of different stakeholders. Interestingly many of those interviewed, including women, actually rationalise and the practice, morally legitimising it. After a point, the audience are left confused if phanek is a symbol of patriarchy’s inherent gender oppressive character, or else the embodiment of a mystical gender power. Perhaps there is a bit of both in good measures, but the director is unsuccessful in fitting them into any coherent ideological perspective. With its ideological layering thus lost in its own narrative labyrinth, the film become no more than just another account of a traditional female wear.

Beyond Blast

This is a biographical film. The film traces the valiant fightback of Konthoujam Maikel both of whose legs had to be amputated after he was caught in an improvised explosive device, IED, explosion at Pourabi village on December 16, 2007. What the film suffers from is a restrictive linearity of narrative. It traces chronologically the progress of a young man from utter devastation to emerge as a fighter against all overwhelming odds. What is missing are pictures of his psychological struggles, and his setbacks and triumphs on these battlefields. Towards the beginning, there were some hints that there would be these other layers of complementary narratives, as for instance when Maikel is shown beside a portrait of controversial but superb para-Olympic champion Oscar Patterson, who too fought to become a champion after losing both legs. This expectation however is short-lived. The context of the bomb blast at Pourabi that injured Maikel is also not explained adequately. Is Maikel’s fight only a personal heroic struggle? Is he saying bomb blasts are indiscriminate and therefore not a legitimate weapon even in a conflict situation? Or is his message also a call for a comprehensive resolution to the conflict in Manipur which led to violence such as the blast that cost him his legs? These questions are left mostly unaddressed.

Meiram – The Fireline

This is story of individual heroism, and relates to what can be described as a revolutionary environmental movement initiated by Moirangthem Loya at Punshilok on the Langol hill range, rejuvenating a 300 acre forest through dedicated replantation and preservation work. The particular focus of the film is on a strategy of using controlled fire to clear narrow strips of shrubs and grass in the periphery of a forest in order to prevent wild forest fires spreading and consuming the rest of the forest. These wild fires are usually the result of reckless forest clearance technique employed by many traditional communities in Manipur. The film has a rich array of visuals, giving the audience a sense of the richness and beauty of the forest’s flora and fauna. What it lacks is a narrative thread to bind them all into a cohesive story line. A strong voiceover narration, such as in a David Attenborough wildlife episode, would have made the film stand out. For instance, when a beautiful bird or a snake is shown, the audience are left bewildered what species these belonged to, what their ideal habitats should be and how these are being degraded etc. Indeed, many amongst the audience, particularly if they are not already familiar with forest fires and their prevention methods in Manipur, would find it difficult to grasp what exactly all the efforts of the characters in the film entailed, and how they are relevant.