Other than the several theatres of world renown of Manipur, coming out with headline making production at regular intervals, there are many lesser known theatre groups doing stellar work, though of late there seems to be a slump in activities on this front in recent years. Probably it has a lot to do with COVID, but also undoubtedly there is seemingly a creativity exhaustion. As the older generation of theatre personalities age and recede into the background, the fear is, the creative atmosphere in the state may not be alive enough to nurture a younger generation of theatre directors and actors able to inherit the mantle of the state’s greats and hold their own forts. To keep the issue alive, and to remind theatre lovers that even the government’s own Jawaharlal Nehru Manipur Dance Academy, JNMDA, once used to be coming out with superlative productions regularly, we are running a review of a production premiered 18 years ago.

Jawaharlal Nehru Manipur Dance Academy, JNMDA, “Khamnu: Genesis of Her Birth” a dance drama in the Manipuri dance tradition was captivating. Only masters can tell an age-old story, told hundreds and thousands of times before through generations and still hold audiences to rapt attention. Khamnu does precisely this.

Very briefly, the story explores and depicts the origin of a well-known but rather underplayed character from Manipur’s popular epic “Khamba Thoibi” – Khamba’s elder sister Khamnu, who raised him through grinding poverty, having lost their parents while she was only a child and he an infant.

The title of the present production is a little misleading though, for the drama that unfolds on stage is not so much about Khamnu, but of her parents. But this is only understandable, for telling an entire epic in a one-and-a-half-hour stage show, is next to impossible.

Again, as in all other epic tales, there are too many narratives branching out of the central theme, each complete enough and absorbing enough to be independent stories by themselves. And there are further branches out of these branches, each again capable of holding their own as independent stories.

Khamnu’s parentage hence is one such “epic digression”, to describe the story in terms of a Homeric story telling device.

The story is well told. Th. Chaotombi Singh, the director, script-writer and choreographer, has done a remarkable job. The scenes are economical, the drama arresting, the dances captivating and flow of events smooth and seamless. The credit must however be shared with his entire troupe, who were all without exception, good dancers and actors combined.

The story begins in mythical times.

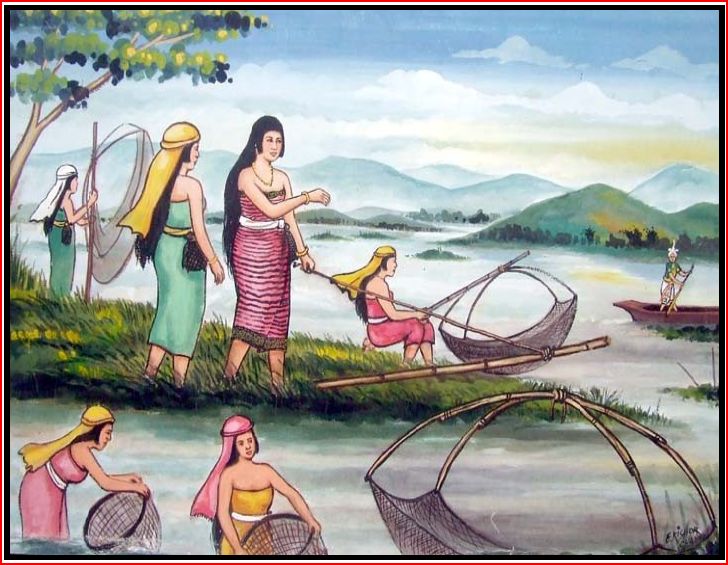

Seven daughters of Soraren (the sky) are seen enjoying themselves, dancing and frolicking, as birds would. Chaoba, a young man, possibly a hunter, enters and gives chase. He ultimately captures the maidens but frees all except the youngest, Araileima, who he takes away to be made his spouse.

They cohabit for sometime, but Chaoba in time wants to abandon her and move on. Fury overcomes Araileima, and she kills the man she has come to love.

Chaoba reincarnates as Puremba in Moirang and Araileima as Ngangkhaleima, to re-enact their love story. The two ultimately are also to become the parents of Khamnu and Khamba. The play however depicts Puremba as only the foster father of Khamnu, as Ngangkhaleima by force of circumstance had to cohabit with the King of Moirang and conceived Khamnu before she became Puremba’s wife.

Puremba at the time of his bizarre rendezvous with his future wife, Ngangkhaleima, had become a powerful noble in the King’s court.

He is sent to subdue the rebellious chief of Salangthen, which he does, but while returning from the expedition, he encounters Ngangkhaleima, a wild woman. He captures her and brings her to the King. The legend says it, but the play does not, that Puremba and Ngangkhaleima took a liking to each other at first encounter.

The king takes a liking to her and Puremba reluctantly gives her to him. In the palace, she learns to be a lady and the King makes her one of his many wives.

Nine notorious tigers appear in the kingdom and terrorize the people. Puremba shoulders the responsibility to end the terror. He lives up to his commitment. Overjoyed, the king gifts Ngangkhaleima to Puremba and the two lovers from the mythical times reunite and the heavens smile.

Again, although not too convincingly communicated by the play, a brochure circulated to the audience says that the theme of the play is also to expose the shoddy treatment of women even in ancient times.

What comes across however is not any kind of didacticism that the brochure mentions, but of a depiction of the promiscuous and consanguineous mores of any ancient society. And as Friedrich Engels says in his classic “Origin of Family, Private Property and State”, in ancient societies where inheritable private property is still unheard of, this is likely to be so.

Again, the instinct to transcend to a monogamous-monoandrous (one man one woman) relationship, from the then promiscuous society, was initially stronger in the woman, for then the father of her children would be known and the responsibility of parenthood shared.

With the advent of settled agriculture and herding comes private property and a patriarchal order emerges with the patriarch as the owner of the surplus. Consequent upon this, the patriarch too begins to want definite heirs and hence the notion of family is consolidated.

Reflections of this social transition, although inadequately explored, are visible in JNMDA’s “Khamnu”.