A major issue of post COVID economic recovery has been the debt crisis engulfing several developing countries. The debt crisis that developing countries face around the world is a lethal combination of high inflation stoked by the Russo-Ukraine war, global tightening of interest rates by central banks to fight this inflation and increased poverty that many countries have faced thanks in large measure to the lockdowns across the developing world to combat the corona crisis.

However, an integral part of the debt crisis that afflicts developing countries are the legacy issues of neo-colonialism and predatory economic policies, followed in large measure by countries like China.

The debt crisis has sparked a global call for restructuring of loans of the developing countries. India, the current G20 president is leading the global South in calling for debt sustainability. On a critical analysis, the neo-liberal ideology of economics can be blamed for the debt crisis that developing countries face. Neo-liberalism has made dependence on external financial institutions and large creditors a ‘normal’ economic policy.

This research paper seeks to undertake a detailed study of the genesis of the debt crisis, while doing a case study of certain countries facing this economic crisis. It will also as a part of its research methodology will be exploratory research which seeks to understand the global scenario of the debt crisis decoding in the process, the predatory economic policies of China, the impact of COVID-19 and some policy prescriptions on how to come out of this fiscal imbroglio having broader societal implications.

Introduction

In the global history of capitalism, debt is considered to be an integral part of how societies and institutions particularly economic institutions function. However, debt is considered sustainable as long as it backed by substantial financial assets or the requisite capital to service its(debts) requirements. The nature of debt can range from very simply any kind of due that any individual can owe at any period of time that requires to be paid back within a stipulated period of time to the complex nature of debt at the macroeconomic levels of nation-states expressed in the form of loans to foreign countries by individual countries, multilateral financial institutions, credit extended to countries in need, trade in commodities which requires settlement in currencies concerned etc. These constitute a part of the overall debt profile of any country. Debt can be both internal and external, however, in the context of this paper, debt will be understood in terms of external loans and financial aid.

Simply put, in the context of macroeconomy, debt denotes any loan or financial help a country has taken from another country or a coalition of countries or multilateral financial institutions that need to be paid back, in the meantime, interest rate of uniform nature will be imposed to service the financing cost of such a loan.

Debt is an integral part of capitalistic ecosystem, without the flow of capital and the accumulation of debt (at sustainable levels) no country’s economy can hope to function sustainably, this is more so in the case of a globalised world marked by all round financial globalisation where there has been a free flow of capital and finance in cash or in electronic format.

Of late, developing countries have been experiencing severe debt crisis which has sparked a re-run of the Eurozone crisis of the early 2010s. A lot of factors which, despite, being complex are related here, such as the pernicious impact of COVID-19 pandemic, predatory economic policies of China under the garb of the Belt & Road Initiative, and the neo-liberal economic policies of the West following the global recognition of capitalism in what Francis Fukuyama calls in his book The End of History & The Last Man as the end of history.

Genesis of debt crisis

The genesis of this debt crisis of the developing countries must be, looked at from a historical point of view harking back to the 1990s, economic globalisation especially financial globalisation to a large extent was responsible for the debt crisis, this is evident from the fact that, financial globalisation while undoubtedly led to unprecedented economic prosperity to large sections of humanity led to the rise of neo-liberalism and its associated processes of liberalisation, privatization, globalisation(LPG).

Joseph Stiglitz, former president & chief economist of World Bank, in his book Globalisation & Its Discontents1 argues that the multilateral institutions like World Bank and IMF forced developing countries like Kenya, Botswana, Brunei, Nigeria to open up at an accelerated pace, as a result of this, Multinational National Corporations flooded their countries with investments which provided the technocrats of these MNCs immense economic power, often coercive, to arm twist the governments into providing them concessions, the result- the countries with a lack of protectional measures and lack of strong domestic industry failed to compete with the more advanced multinationals leading to mounting debts, which made them beholden to the multilateral financial institutions to bail them out.

This was a crude manifestation of neo-colonialism of the west which had only changed over the years reflecting the continuation of the financial colonising mentality of the West which has been brilliantly exposed by J Sai Deepak in his book India That is Bharat2.

Neo-liberalism, whose advocates include Fredrick Hayek3, Milton Friedman were staunchly opposed to the state intervention of any kind, whatsoever, and advocated the resurrection of the laissez-faire approach to the functioning of global economy, in this context, the economic growth of the developing countries.

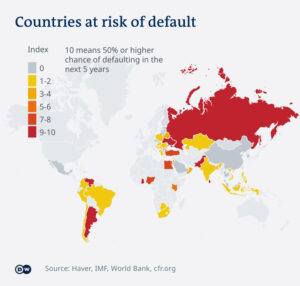

Global Scenario of the crisis

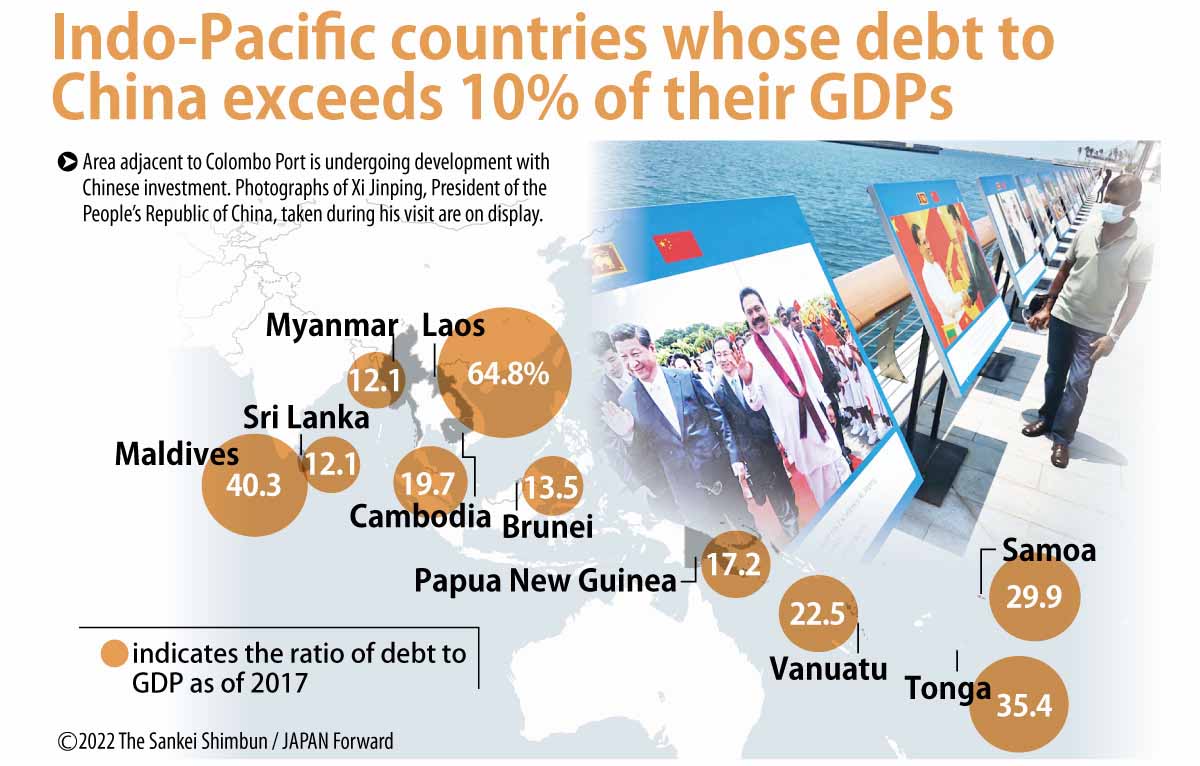

The debt crisis engulfing the developing countries is ubiquitous, spreading to every nook and corner of the globe, in South Asia, it has already afflicted Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh to some extent, and Nepal. In Africa, multiple countries such as Malawi, Botswana, Nigeria, Uganda, Mozambique etc are reeling from this crisis and are calling for a restructuring of their loans which they owe to China, World Bank etc. In South-East Asia, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos is suffering from this crisis.

East Asia is relatively unaffected from this menace. In Europe, central & Eastern European countries are reeling from this crisis, countries like Poland, Bulgaria, Romania etc are suffering. Interestingly, West Asia seems to be insulated from this crisis owing to the fact that the high prices of crude oil thanks to the Russo-Ukraine war caused the countries to quickly and prudently service their debts in a short period of time.

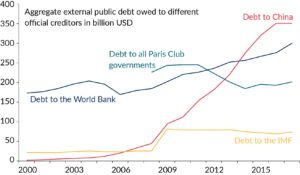

Predatory lending of China

China, the world’s second largest economy and the country with the largest foreign exchange reserves is the manufacturing hub of the world. Concomitantly, it is expected of this gargantuan country to play a key role in trade and economic diplomacy globally, and, it has been playing such a role. However, China’s flagship infrastructure project Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched back in 2013 with the professed aim of reviving China’s ancient Silk Route by weaving the world in a dense intermeshed network of railways, roadways, ports, energy projects etc have become a major source of debt crisis in developing countries.

China, under the garb of BRI, conducts what is known as debt trap diplomacy. In this type of economic diplomacy, the Chinese government will invest massive amounts of money in the infrastructure and other core sectors of a country at high rates of interest, on the surface the scheme of things will appear to be very attractive, but the sheer scale of investment ends up overwhelming developing countries in question and puts them under debt, as they are unable to pay back the loans at such exorbitant rates of interest. This results in accumulation of debt and makes the host country dependent on China, which starts dictating their own terms and conditions, often detrimental for developing countries’ economic sovereignty.

Some excellent examples include Sri Lanka whose foreign debt is almost one-fifth Chinese4 followed by India inter alia. The Chinese have as a result of this debt trap diplomacy sparked an economic crisis in Sri Lanka (one of the many causes among others) causing the former to ask for restructuring of the loans by lending from the IMF.

The case of Greece, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Maldives, Cambodia etc are the same. Chinese predatory lending practices have been primarily responsible for sparking this debt crisis. In fact, African countries’ debt crisis vis-à-vis Chinese loans is at best a ticking time bomb waiting to implode anytime. Weizhen Tan5 of CNBC argues that one example of those opaque loans is how Chinese loans to Venezuela were denominated in barrels of oil, according to a speech last year from David Malpass, the current president of the World Bank who was then the U.S. Treasury Undersecretary for International Affairs.

Sam Parker & Gabrielle Chefitz, writing for The Diplomat6 state that as China continues to loan billions to construct often commercially non-viable infrastructure projects in debt-strapped nations, the authors believe this is a pattern that has the potential to repeat itself. In a report published recently by Harvard University’s Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs, the authors identify 16 developing countries — from the Horn of Africa to far-flung Pacific Islands — that may become vulnerable to what we’ve termed “debt-book diplomacy.” Many of these countries have taken on massive Chinese loans with little clear prospect for repayment and have strategic assets or diplomatic sway that China could demand. Such deals could undermine U.S. interests and foreign policy in Asia.

As Beijing accumulates more economic leverage through lending, recent evidence suggests it won’t be shy about using its distinctive state-and-market model towards advancing the ruling party’s global political goals. China’s practice of geoeconomics has been as creative as it’s been proactive: from shuttering South Korean-owned supermarkets in protest of a missile system deployment, to decimating Norway’s salmon exports as punishment for a Chinese dissident winning the Nobel Prize.

Therefore, it is very clear that China’s predatory lending is not only ubiquitous but is essentially predatory in nature, while China criticises the neo-colonial attempts by the West, China is doing the same thing, albeit, in a highly sophisticated and surreptitious manner. In this context, it is noteworthy that India hasn’t fallen for that trap. Notwithstanding, the bourgeoning trade deficit that India has developed with China in the form of $71 billion7, yet, India is in much more comfortable position compared to other Asian countries as its foreign investment under the FDI route isn’t only Chinese in nature, the portfolio of foreign investment is diverse. India, however, has maintained a special vigilance on the issue of Chinese FII investment in the country’s debt and stock markets. The acquisition of a miniscule share by the China’s People’s Bank of China in HDFC bank8 was enough to raise eyebrows in the Indian trade and foreign policy establishment leading to more cautious approach on that front.

COVID-19- the silent killer

Apart from China’s predatory lending practices under the garb of development, another, albeit very recent event of astronomical proportions has exacerbated the debt crisis of developing countries- the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, the mammoth loss of lives, the lockdowns across the world caused a drastic decline in economic activity leading to accelerated pace of debt rising.

Lack of economic activity, followed by gradual re-opening of economies which saw unusual spikes of inflation around the world causing gradual hikes in interest rates around the world by central banks. This increased the burden on developing countries’ ability to pay back their loans to their creditors causing the possibility of global loan defaults. Frantic calls for restructuring of debts to sustainable levels were called for by developing countries, especially the African countries which were the hardest hit from the pandemic.

What made it increasingly difficult for the developing countries in this abnormal phase was the lack of economic and industrial activity. According to the laws of capitalism, industrial activity is the sin qua none of the present human civilisation, any attempt to stifle or reduce it will spell doom for any country. The COVID-19 pandemic brought industrial and other economic activities to a grinding halt, leading to a default crisis of developing countries.

Even a developed country like Italy was unable to escape the scourge of this pandemic when seen from the economic perspective.

Heribert Dieter9, a visiting professor at the Asia Global Institute, The University of Hong Kong argues in an article for the renowned think tank Observer Research Foundation that the main point is the improved sustainability of monetary policy. An interest-free environment, in particular in OECD countries, resulted in dangerous developments. The negative costs of borrowing resulted in an unprecedented asset-price inflation.

Prices of shares, real estate, and other assets where supply is limited, for instance vintage cars, shot up. That trend, driven by the monetary policies of the major central banks, has resulted in social tensions which in turn is detrimental for smooth functioning of any economy as the fundamental political laws of capitalism require political and institutional stability. Those without assets were exposed to the negative consequences, in particular higher cost for housing, without benefitting from the low interest rates. The current return to a monetary policy with interest rates, if still negative in real terms, is thus, a welcome development.

After years of relative calm in financial markets, turbulence is back. Policymakers in both OECD- and developing-countries should use this opportunity to improve the current framework for debt restructuring and crisis management.

Russo-Ukraine war

To make matters worse, the Russo-Ukraine war of 2022 which is still continuing has sparked a fresh crisis. The outbreak of the war caused skyrocketing of hydrocarbon products like crude oil and natural gas. As these commodities are important for developing countries for their continuous proper functioning, high prices are obviously a burden.

The high prices of oil and natural gas caused central banks around the world to deal with inflation, they dealt with it by jacking up interest rates. The RBI has since May 2022 hiked the repo rate by 250 basis points to bring down inflation. The Federal Reserve of US did exactly the same resulting in spill over effects on other countries.

The increase in interest rates caused turmoil in the financial markets leading to marked increase in the yields of bond markets and increasing the burden of servicing loans on the common man. On the macroeconomic level, the cumulative effects of the global interest tightening & lack of recovery from the pandemic led to countries in the African and Asian continents (especially South Asia-the case of Nepal) to call for debt restructuring.

The situation with the developing countries in Europe, especially, Eastern Europe is all the more complicated, even as the European Union has banned the import of Russian oil and natural gas to show their solidarity with Ukraine, the Eastern & Central European countries are finding it difficult to sustain high inflation in their countries to replace Russian oil & gas. Also, the pandemic has left them with high amounts of debt which needs to be paid back. Therefore, it is a catch-22 situation for them.

Case study- Sri Lanka

To highlight the gravity of debt crisis afflicting developing countries, it is essential to see the condition of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka, one of the most promising and vibrant economies was considered to be a country with bright prospects post the civil war period. However, Sri Lanka’s condition deteriorated by a lethal combination of Chinese predatory trade policies and subsequent mishandling of the economy by the Sirisena & Rajapaksa governments.

Sri Lanka is an important node of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, in an attempt to balance China against her northern neighbour India, Sri Lanka started courting Chinese investments under the BRI not knowing what was lurking in the dark for them.

As Chinese investments increased, Sri Lanka continued to sink in the quicksand further, when a time, probably 2017 when the Lankans realised that the overwhelming cost of Chinese loans had overwhelmed them, so they sold the Hambantota port to China at a very low cost10. As conditions continued to worsen, came the COVID pandemic.

The pandemic ravaged the Sri Lankan economy, putting the critical tourism & hospitality sector of Sri Lanka, which accounts for over 70% of Sri Lankan foreign exchange out of order. To make matters worse, the Rajapaksa government which was elected by the people in early 2019 under the leadership of Gotabaya Rajapaksa with a thumping majority mishandled the economy badly- this included immediate banning of chemical fertilizers in favour of organic fertilizers, increasing borrowing from the world markets and massive corruption at the top echelons of the government.

The sum total of all these factors led to economic collapse in Sri Lanka, the country is currently grappling with the worst economic crisis that it has faced in decades. Sri Lanka is currently negotiating with the IMF to bail it out to restore the financial health of its bed-ridden economy. Sri Lanka has, however, managed to get a $3 billion loan from the IMF11 following the approval of its creditor countries like India, China, Japan and others regarding the restructuring of its high external debts.

It is therefore a wait and watch scenario in Sri Lanka.

Policy prescriptions

To ease the debt burden on developing countries, some policy prescriptions are worth mentioning-

Firstly, reaching a global consensus on the need to ensure sustainable restructuring of debt burdens of the developing countries. In this context, India, which is the current G20 chair can take the lead that both as a developing country and sixth largest economy, it can bring the global north and global south on a single platform to address this issue.

Secondly, multilateral financial institutions must synergise their strategies to urgently address the issues surrounding the sustainability of debt that the countries of Africa require in the aftermath of COVID pandemic and the continuing Russo-Ukraine war.

Lastly, if possible, accepting some haircuts to provide overall relief to developing countries’ needs by the developed world, this is more applicable in the case of China, which single-handedly responsible for putting many of the developing countries in debt imbroglio.

References

- Stiglitz, J. (2017). Globalization and its discontents. Penguin Books Ltd.

- Deepak, J. S. (2021). India that is Bharat: Coloniality, Civilisation, Constitution. Bloomsbury.

- Gauba, O. P. (2018). Concept of Ideology. In An Introduction to Political Theory (7th, pp. 32–34). Mayur Books.

- (2023, March 8). China offers Sri Lanka debt moratorium, promises deal on debt treatment & nbsp;. Deccan Herald. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.deccanherald.com/international/world-news-politics/china-offers-sri-lanka-debt-moratorium-promises-deal-on-debt-treatment-1198229.html#:~:text=By%20end%2D2020%2C%20Sri%20Lanka,China%20Africa%20Research%20Initiative%20showed.

- (2019, June 12). China’s loans to other countries are causing ‘hidden’ debt. that may be a problem. CNBC. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/06/12/chinas-loans-causing-hidden-debt-risk-to-economies.html

- Sam Parker and Gabrielle Chefitz for The Diplomat. (2018, June 1). China’s Debtbook Diplomacy: How China is turning bad loans into Strategic Investments. – The Diplomat. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/chinas-debtbook-diplomacy-how-china-is-turning-bad-loans-into-strategic-investments/

- Bureau, T. H. (2023, March 29). 2022-23 trade deficit with China crossed $71 billion by January. The Hindu. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/2022-23-trade-deficit-with-china-crossed-71-billion-by-january/article66675092.ece

- China’s Central Bank buys 1% stake in HDFC. The Economic Times. (n.d.). Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/chinas-central-bank-holds-1-stake-in-hdfc/articleshow/75104998.cms

- Dieter, H. (n.d.). What to do with the potential debt crisis looming over the world? ORF. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/what-to-do-with-the-potential-debt-crisis-looming-over-the-world/

- Stacey, K. (2017, December 11). China signs 99-year lease on Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port. | Financial Times. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/e150ef0c-de37-11e7-a8a4-0a1e63a52f9c

- Al Jazeera. (2023, March 21). IMF approves Sri Lanka’s $2.9BN bailout. Business and Economy News | Al Jazeera. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/20/imf-approves-sri-lankas-2-9bn-bailout

The writer is PG-II (Political Science with International Relations), Department of International Relations, Jadavpur University. He was also a research associate for think tank Defence Research and Studies(DRAS) and a columnist.