The debut feature film of Lakshmipriya Devi, Boong, revolves around longing, resilience, and sacrifice in the life of a mother. Alongside this, the exploration goes into a son willing to sacrifice it all just to see his mother happy, which means crossing over to the other side of the border to find his father, who doesn’t want to come home anymore. A young boy, Boong, dreams not only of his father’s return after years of absence but of finding him and presenting him to his mother, Mandakini (Bala Hijam), as a gift. He wants to thank her for enrolling him in an English medium school, believing that bringing his father home would make her smile. His ultimate dream is to fulfill this heartfelt wish.

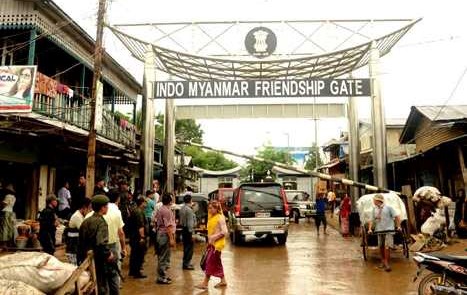

Lakshmipriya’s debut feature-length film places viewers in Mandakini’s position, drawing attention to her expressions as she waits for her husband. Though she holds onto hope, her face reveals the quiet resignation of someone who no longer believes he will return. She repeatedly dials Joykumar’s number, only to hear automated responses, either that he is busy or his phone is switched off. While she longs for him to come back, she resists searching for him in the border town of Moreh, fearing that discovering the truth will shatter her completely, even though, deep down, she knows he is alive.

A brilliant debut at the prestigious Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) and competing in the second edition of Eikhoigi Imphal International Film Festival, the film sees through the eyes of Boong and Mandakini tackle pressing issues. It raises questions like, is Manipur still grappling with insurgency? Is the gap between high and low-income groups widening? Is there racial discrimination against non-native Manipuris? How does life remain uncertain on the India-Myanmar border?

There are other forms of light that the film casts on the socio-political landscape of Manipur: the insurgency, economic difficulties, and specifically, the strength of women. Fittingly for a state with harrowing, historic women-led movements such as Nupi Lan and the iconic all-women Ima Keithel market, Mandakini, after her husband leaves, sees to it that Boong has a private education and strives to survive through selling handloom items.

Being a single mother, she constantly faces exploitation sometimes from her fellow community and her relatives. But help arrives in the guise of Sudhir, father of Boong’s best friend, Raju Agarwal (Angom Sanamatum). Ironically, despite the fact that Raju’s family has settled in Manipur for more than one hundred years, they are still considered “outsiders,” reflecting ingrained societal prejudice.

The banning of Hindi cinema in Manipur is touched upon in this film. The character of Pradhan Mani is a closet subscriber to the Hindi film cassettes, watching them secretly in violation of the ban. He even has a small theater inside his home for others to watch Hindi films. When people told Mandakini that her husband was dead and a death certificate was provided to her, signed by Pradhan Manipur. Mandakini, desperate for answers about her husband, threatens to expose him to the militant group if he refuses to tell the truth.

Depending on point of view, people hear the word Homo and respond differently. Some view it positively, while the others take it negatively. Our perceptions arise from the teachings and experiences we undergo. For Boong, it was bad. In the opening scene of the film, he mischievously alters his school’s name from Oja Hemochandra Boys School into Homo Boys School. But later in the course of his journey, this attitude is later contradicted when he was helped to find his father by JJ, an LGBTQ+ character played by Jenny Khurai.

The movie reveals a very layered and sweeping study into the culture and way of life of Manipur, but is it really banging on a live nail? Probably a yes-no. Production value is good, yet authenticity fails in certain representations, although fictional. One of the outstanding examples would be the way Boong speaks. His pattern of speech is very distinct from his parents, who belong to the Meitei community. On the contrary, his friend Raju Agarwal speaks fluent Manipuri but with a native accent while his dad, Sudhir, has a Rajasthani accent though he claimed to have lived in Manipur for a long long time.

One scene is a portrayal of Thabal Chongba, a traditional folk dance of Manipur. The visuals are stunning, in which dancers in coordinated colors, along with the cinematography, seem to encapsulate a dream-like atmosphere. However, this thabal chongba is way livelier, and it is presently a few shades more colorfully spruced up. The few artistic liberties taken in its portrayal make for an engaging spectacle but do not reflect how the dance is performed in the real world. In the same light comes in JJ’s character, a performer in Moreh town, built in an amusing, beautiful way yet quite untrue to the actual dynamics of Manipur. A few sequences are expressly Bollywoodish and weaken what some audiences would consider “Manipuriness.” This may affect the perception of Manipur for an outsider quite considerably.

At 1 hour and 32 minutes, the film stitches together Boong’s search for the father with the journey of Mandakini, centering around pressing issues such as disparity in wealth, insurgency, human greed, LGBTQ+ identities, and migrant conditions in Manipur. Through Boong’s eye, an outsider becomes cognizant of the complex reality of the state. Yet does it genuinely offer a true representation of Manipur? The people of Manipur and those who understand its intricacies are best suited to answer this question. Media scholars and film critics should check out this film to foster discussions about whether its impact is predominantly positive or whether it risks reinforcing a distorted narrative.