The news of the death of Yenkhom Ongbi Hemabati, wife of Dr. Yenkhom Bheigya on February 9 last year came as a shock, although she was of a ripe old age of 94. Here is a lady who had been such a vivid and interesting living witness of the forgotten theatre of the World War II that Manipur became in the early 1940s when the Japanese Imperial Army’s Burma campaign stormed into the state and the neighbouring Naga Hills District of the then united Assam. Field Marshal Sir William Slim, in his monumental war diary, published as book after the war, titled: “Defeat Into Victory”, called this confrontation in the Imphal-Kohima sector between the Japanese and Allied forces as some of the most bitter in the entire war although these were lamentably overshadowed in the media by the North Africa campaign which was more immediate to Europe and the continent’s interest. He and other chroniclers of the war on this front even were of the opinion that the severe reverses suffered by the Japanese troops here served as the turning point of the Japanese war fortune overall.

Accounts of the war however have been mostly from the point of view of those engaged in the war and very little of it have been as seen by people alien to war but whose home grounds had been transformed into killing fields without their consent. I had interviewed Hemabati years ago, and her account of the war as she witnessed and it struck me as extremely interesting. The news of her death also reminded me of my lethargy. I had still not put her story ink on paper. I did so the very next day after her death. After a brief hunt in my private library for the diary I had noted down the interview. Thereafter, I was at my working table.

Hemabati grew up in Sibsagar in Assam. She belonged to an affluent Meitei family there, and it is said her father was an important executive in a tea garden. She met Yengkhom Bheigo in her hometown when he had come to study medicine in the medical college in Dibrugarh. The two fell in love and eventually married and that is how she came to be living in Manipur some years before the war broke out. Here is her story:

“We came to learn of the imminence of the war reaching Manipur months before it actually broke out. There were plenty of rumours, some plausible, others wild. One of them said if the Japanese took Singapore, they would arrive in Manipur before your day’s laundries dried.

“Prophesies from the purans (Meitei ancient books of prophesies) began floating freely, with nobody actually knowing how they originated. The one that caught the people’s paranoid imagination most was that the flight of 18 white egrets across the Manipur sky would signal the beginning of the war. When the phenomenon was sighted the advice was to flee and take shelter at places with names beginning with the consonant ‘K’. Everybody watched the skies day after day for the white birds with anxious expectation and apprehension. My son Jotin, the eldest of 11 siblings was 11 years old at the time.

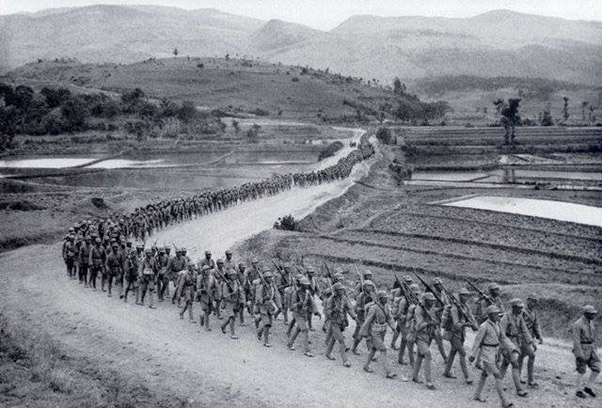

“The Allied troops began arriving into Manipur in endless convoys. Soldiers of different colours and built that we have never seen before, huge armoured military vehicles, tanks and anti-aircraft battery began filling up our roads. It all made up for a very awesome and intimidating picture.

“The war time administration then began bombarding the place with pamphlets, instructing the civil population of the dos and don’ts during the war. One of the many advices was to dig trenches to hide during bombing raids. Trainings were also imparted on these precautionary measures. Amidst the growing nervous tension, we continued to watch the skies for the 18 egrets in flight.

“My husband was then posted at Thoubal. He left me and the children in the relative safety of Lilong but he became so busy those days that he was unable to visit us for extended periods. It was a time when refugees of Indian origin began pouring into Manipur from Burma. Many of them, especially women and children, were sick and on the verge of death from starvation and fatigue. He was busy attending them.

“One day he showed up at our residence at Lilong briefly. He seemed depressed. He told us the story of a refugee then on his last leg, brought to him for treatment. The unfortunate man had been suffering from cholera for some time during the trek to India. My husband treated him but it became soon evident to him it was too late to rescue the dying man. On his deathbed, the man presented my husband a tin box which he had lugged all the way from Burma and said it contained money, weeping that he was to die without seeing his family. My husband said he took the box and although the dead man had gifted it to him, handed it over to the British wartime authorities, telling them to do what they thought was the needful.

“My husband was honest to a fault and had no particular cravings for unearned money. His story however made us all grieve for the dead man.

(Did the white egrets appear? I interrupted impatiently at this point).

“Yes, yes! They did come flying. But they were not the birds that we were expecting. Instead, they were white airplanes. The first time they came they did not unleash their loads of fire and brimstone. As per instructions we ran and jumped into our trenches but the planes simply turned and flew away. The first day gave us a very wrong impression of the war. We could not figure out why the White men were so fussy about airplanes and the trench routine.

“A few days latter, on May 10,1944, the airplanes returned and shocked us all out of our complacency, pouring on us bombs that exploded like unending thunder claps. Many said there were 18 of them. So perhaps the puran prophesy did come true.

“It rained bombs continuously from then on for a long time. A lot of familiar landmarks were flattened. A refugee camp too took a load and many unfortunate souls were killed. The spectacle of terror was simply beyond words.

“One day my husband turned up at our residence again very briefly. He said he had been transferred to Churachandpur and would be proceeding there immediately. He asked us to stay on at Lilong until the fightings lightened and then to try make it to Moirang. He had asked Uncle Nongthonba in Moirang to help make it possible.

“At the time I had four children. My eldest was only an 11 years old boy and there were already three girls after him. My husband took my son and a cousin, a young man then, with him to Churachandpur, leaving me with only the three little girls. Those were frightfully lonely and insecure days. Nights were spent in total darkness with the children as we were forbidden to light up our lanterns.

“There were plenty of military vehicles everywhere but no public transport system at all those days. I decided to hire a boat to go to Moirang as my husband instructed me. The war had suddenly and quite eerily quietened after the initial salvo of bombings. We were unaware where the front had shifted.

“Uncle Nongthomba arranged a huge boat, capable of carrying 60 sacks of paddy for our transport to Moirang. I gathered whatever little belongings I had, packed all the food grain in my possession, and then prepared two packets of chempak (flattened rice) and kabok (sweatmeat) for the two bigger girls and told them to eat whenever hungry before seating them in the boat. I took the suckling little one on my lap and we proceeded towards Moirang along the Nambul Turel (Nambul River). In those days, Nambul Turel was very much a navigable river that connected Imphal with the Loktak Lake and Moirang on the other shore.

(I forgot to ask her how many days it took her to reach Moirang.)

“At Moirang, uncle Nongthomba was there to receive us. He was immensely hospitable. But after staying for a few days at his house, I decided to proceed on my journey towards Churachandpur where my husband was. I asked Uncle Nongthomba for help, and the genial gentleman, influential as anybody could be in Moirang, managed to arrange a bullock cart to take us to Churachandpur after much difficulties. The reluctance was not surprising. After all it was wartime. Danger lurked everywhere. The hill roads were not in good shape either and there were reports of bear attacks along the road we were to travel.

“This did not deter me. I told myself that I had to reach my husband in Churachandpur and was delighted when one bullock cart finally agreed to do the journey. Like in Lilong, I packed my belongings into the cart, made champak and kabok tiffin for the two bigger girls before boarding them on the cart. I then strung up the suckling baby piggy back, tied a length of cloth around my waist to give me strength, took a staff in my hand and proceeded to walk behind the bullock cart on our way to Churachandpur.

(Did you wear shoes? I asked).

“Rubbish! I was barefoot. The weather was extremely dreary, it was drizzling and the ground was slippery, but my determination to reach my husband made me ignore all these and I embarked on my journey.

“The war was still on. Although we were on a deserted road we got the evidence of it once in a while in the distant reports of gunfire and explosions. There were plenty of troops movements on the road too.

“But the areas likely to be bombed were already vacated on the order of the military. What a tumultuous time it was? People having to vacate their homes and flee to rural areas, leaving behind much of their belongings, letting loose their pets and cattle in the hope they would fend for themselves until the war got over and they could be reclaimed.

“When I reached Churachandpur, to my utter dismay I discovered that my husband’s posting was not in Churachandpur town, but in the interior village of Thanlon. I was determined not to turn back.

“When I finally reached my husband’s post at Thanlon, the B-Force Company of the British Army was there. The officer was a Britisher, but most of the troops were Nepali. The White Saheb was a very nice man and my husband got along very well with him. But one day, all of a sudden the B-Company withdrew. The troops left all at once, but for reasons that I do not know, one White soldier was apparently thrown out of the group. I saw the unfortunate man walking out of the camp alone and dejected, in his underwear, heading in the opposite direction of the withdrawing troops.

“Then one day news reached that the Japanese were in the vicinity and a fight was imminent. We were very scared, but my husband said he would go and see the Japanese who were camping a little distance away in the jungle. He said he had no enemies, the Japanese or the British.

“We also saw the Japanese occasionally. They were very likeable. We made friends with the British but so what, we can equally be friends with the Japanese. It was not our war.

“The Japanese soldiers went about in phanek (sarong) in the daytime and it was easy to mistake them for local tribal women. Once some of them in sign language indicated they were hungry. We boiled eggs and offered them on plantain leaves. They relished the meal.

“The Japanese were not too many in number and it appeared that they were in hiding, looking for an escape route. Some would come and others would move away. It had seemed the war had intensified elsewhere in the state and the Japanese were not faring well. I felt sorry for them. My husband was right, neither the Japanese nor the British were our enemies.

“The food was so bland at my husband’s post. We had to eat raw vegetables or else plain boiled rice and vegetables most of the time. During those days I improvised so many dishes to break the monotony. The local tribal population grew a lot of mustard plants for consumption but they were not aware the seeds of this plant could be used. So I had them collect seeds one season and using a mortar and pestle, ground them and extracted oil for cooking. What a divine difference it made to our meals.

“The war concluded while we were in Thanlon. I was told the Japanese were thoroughly defeated and they had to flee Manipur. We were also told later that so many Japanese died everywhere in Manipur.

(I agree with Hemabati. I too witnessed the war as a child, but not so heroically as the grand lady. It was a meaningless war for most of the people of Manipur. A lot of those who suffered the worst fate possible, displaced from homes, maimed, or had relatives killed, etc, still vividly remember what suffering they went through, but not many comprehend why the war was fought on their home ground at all.

I too, even though I belong to the Manipur royalty, had harrowing experiences. We had to flee home along with my mother the queen and a good part of the war years were spent as refugees in makeshift arrangements in somebody else’s portico or some such places.

Apart from the booming guns and terrifying explosions, amidst the chaos and lawlessness, there were also numerous gangs roaming around looting people and homes. Insecurity was the name of the game for everybody those days, even at home.

But Manipuris must distinguish themselves for the ability to make the best of the worst situation. Even amidst all the machine gun clatters and daily reports of deaths, fun and merrymaking did not stop. The lone cinema in Imphal still ran full house, Ras Lilas were performed on schedule, religious ceremonies never stopped. One thing was conspicuous. Inflation was at a peak because of the soldiers who created an unprecedented market for commodities. Prices escalated and those pecuniary minded minted money. It was a war like no other war the place has ever seen till then. The scale and magnitude of destructive violence was incomprehensible. According to Field Marshal Slim, 65,000 troops perished, most of them Japanese. It was even more incomprehensible because it was a war in which the native population shared no issue.

(Translated from Manipuri by Pradip Phanjoubam)