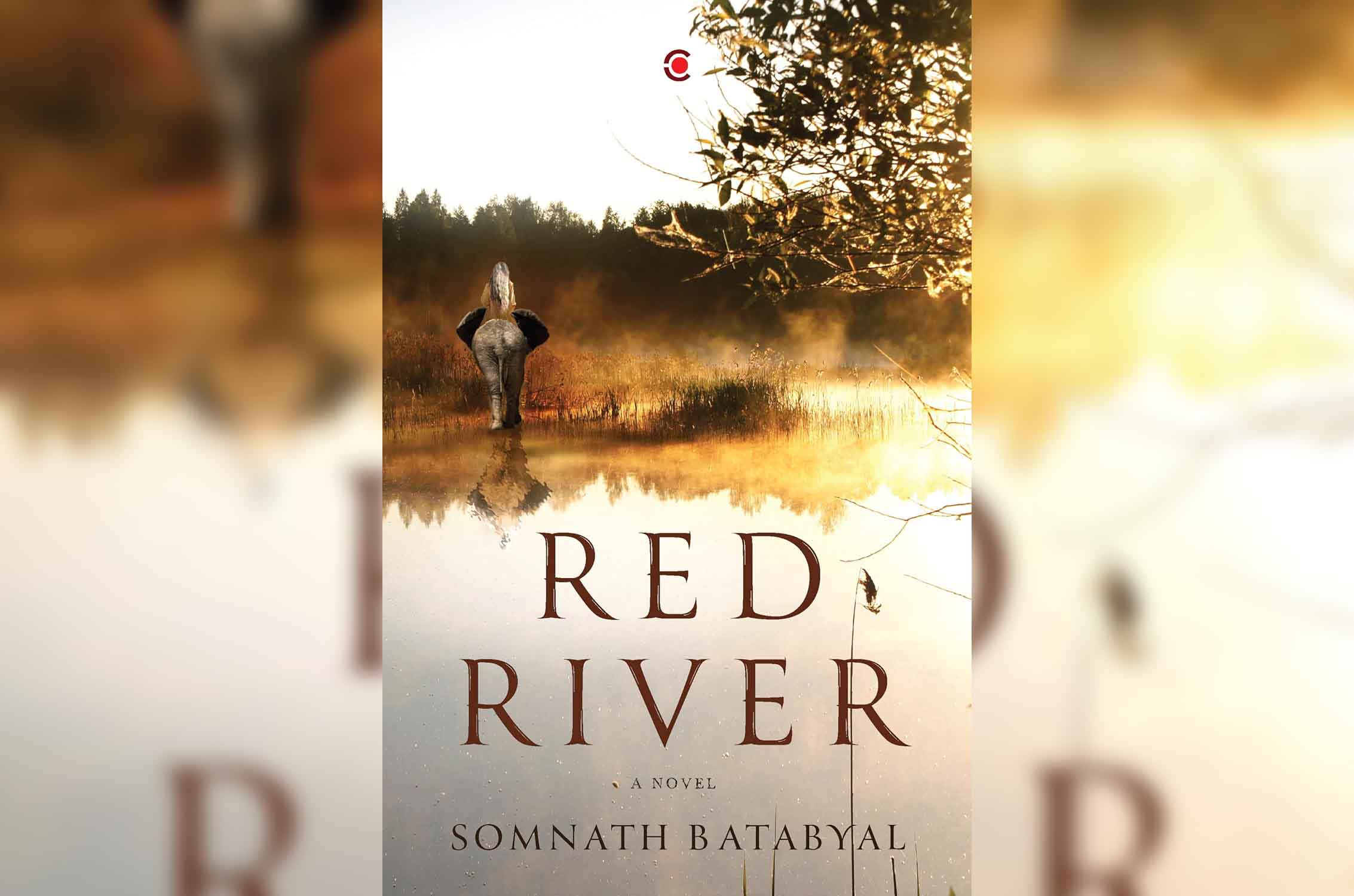

Author: Somnath Batabyl

Publisher: Westland Books A Division of Nasadiya Technologies Pvt Ltd

Price: Rs. 699

The first part of Somnath Batabyal’s novel Red River is a fine demonstration of how literature can see nuances of human predicaments in trying times that history is generally blind to. It succeeds in giving readers a more intimate understanding of Assam’s troubled 1990s.

The story centres around three school friends in the 1990s. Rizu Kalita, son of an Assamese rural school teacher and respected community leader. Samar Dutta, son of Bengali middleclass parents who trace their roots to erstwhile East Bengal, forced to flee homes during Partition and then the mayhem of Bangladesh war of liberation. Rana Singh Choudhary, is the son of a Punjabi Brigadier in the Indian army.

Rizu and Samar, are older friends having been together in a missionary school for boys in Guwahati all along. The Assamese boy is the dominant of the two friends, athletic, bold and carrying traits of his father’s leadership genes. Rana joins the school mid-session in their final year when his father was transferred to the state. He is handsome, tough and outgoing, and at first is seen as a challenger to Rizu’s status in the school. The boys however handle the rivalry maturely, and never allows it to become open, though subliminally it remained to the last.

Deftly reflected in the trio’s relationship, as well as the glimpses of their families, are also the layered nature of identity affiliations amongst Assam’s different communities. Rizu and Samar both consider themselves Assamese at one level but deeper down one becomes the hegemonic Assamese and the other the wily Bongal to each other. Rana does not qualify to be Assamese.

There are no round characters in the novel and instead all are creatures of destiny, swept along by the winds of fate, hence no tearing moral dilemmas or internal struggles with conscience are seen. It is largely a drama in the macrocosm.

The second part descend into melodrama. Rise of anti-immigrant movement heightens the insecurity of Assam’s Bengalis and after a riot, Samar and family makes an escape bid to Bengal. There also seems to be another reason for the flight. Samar’s mother Banalakshmi alias Lucky is suspected to be involved in the assassination of Rana’s father Brigadier Kabir, but this is never fully explained.

A series of misfortunes meet them at New Jalpaiguri. Samar’s little sister Tina gets kidnapped, they also lose all their belongings, including their identity papers and come to be treated as infiltrators by the police and kept in a detention village near the border. Samar and mother escape to Dhaka, leaving his lame father Amol behind. In Dhaka, Lucky reestablishes contacts with the prime minister (not named) whose father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a close buddy of her father’s. They are thereafter brought into the prime minister’s inner circle of associates.

The fortunes of the three friends are allowed to spiral too far apart, so much so that tying up loose ends of the novel’s narrative becomes replete with too many improbable coincidences. When Samar returns to Assam as a tea prospector 20 years later, he discovers Rizu had been assassinated by Rana, then an army colonel when he became entangled after an affair with Rizu’s wife and Samar’s cousin Leela.

Rizu had earlier joined the ULFA but was captured in the Bhutan, thereafter turned SULFA (Surrendered ULFA), and became very wealthy, with a hand in practically every trade, including gun running, the last strangely in partnership with Rana, and to supply ULFA fighters. Rana ultimately ends up committing suicide. It also turns out Rana’s father Brig. Kabir and Samar’s mother Lucky were known to each other, when as a young officer, Kabir rescued Lucky during the Bangladesh liberation war and fell in love but did not marry her. Brig. Kabir also turns out to be the officer in an earlier posting who had killed Rizu’s elder ULFA brother while Rizu was still a kid. Whew!

A slightly abridged version of this review was first published in The Telegraph, and the origina can be read HERE