The United Nations Human Rights Committee questions India about Manipur among others during its review meeting of the fourth periodic report of India on how it implements the provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

India became a State Party to the ICCPR in 1979 with reservations and declarations including common Article 1 of ICCPR and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR): All peoples have the right of self-determination, including the right to determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

With reference to the common Article 1 of the ICCPR and ICESCR, the Government of the Republic of India declares that the words ‘the right of self-determination’ appearing in [this article] apply only to the peoples under foreign domination and that these words do not apply to sovereign independent States or to a section of a people or nation – which is the essence of national integrity.

Till date India has no plans to sign up to the First Optional Protocol, or to revise reservations to the Covenant.

However, the Human Rights Committee on July 16, 2024 concluded its fourth periodic review on how India implements the provisions of the ICCPR. The Committee Experts commended India’s Women’s Reservation Act 2023, reserving one-third of seats in parliament for women, and raising issues concerning corruption and reported violence against religious minorities.

The fourth periodic review of India’s report was after 27 years since the third periodic review in 1997 and it was held on July 15 and 16, 2024 during the Human Rights Committee’s one hundred and forty-first session is being held from 1 to 23 July 2024.

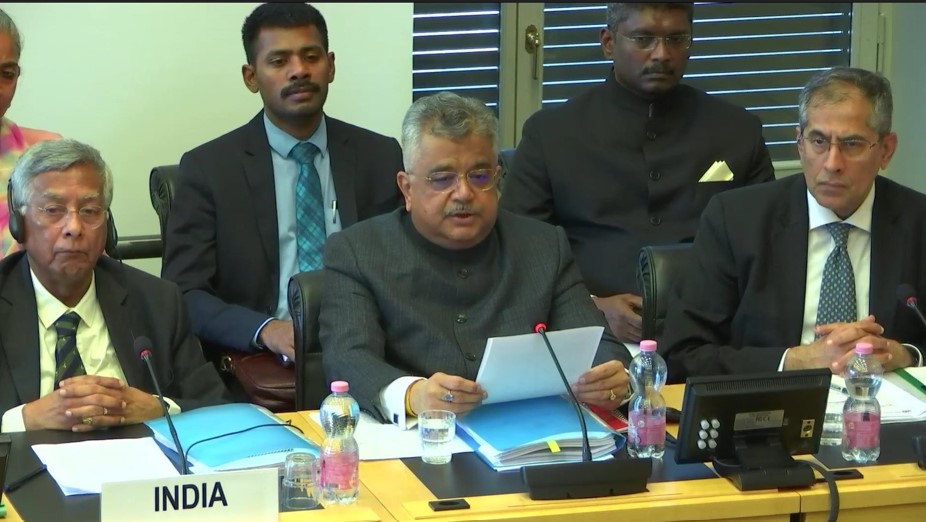

The delegation of State Party of India to the fourth periodic review was made up of representatives of the Ministry of External Affairs; Ministry of Women and Child Development; Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment; Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology; Ministry of External Affairs; Ministry of Home Affairs; Ministry of Minority Affairs; Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities; Ministry of Tribal Affairs; Department of Legal Affairs; and the Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations Office at Geneva. The Indian delegation was led by R. Venkataramani, Ld. Attorney General of India and Tushar Mehta, Ld. Solicitor General of India as Co-Heads of the Delegation.

Significantly, Manipur issue was discussed at least 13 times in the six hours long review on how India implements ICCPR by the UN Human Rights Committee.

Briefing to the UN Human Rights Committee on July 15, 2024 at Geneva, human rights activist and Director of Human Rights Alert (HRA), Manipur, Babloo Loitongbam on behalf of Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association, Manipur (EEVFAM) and HRA, raised the issues of Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) 1958 and the ongoing Manipur violence.

Babloo Loitongbam said, “July 15th, today, is observed in Manipur as Anti-Repression Day. Exactly 20 years ago on this day, 12 mothers of Manipur staged a unique naked protest in front of the Kangla fort, the old palace compound of the erstwhile kingdom of Manipur, which was then under the occupation of the Assam Rifles. They were protesting on the rape and murder of Miss Thangjam Manorama by the Assam Rifles personnel, and the public burst into a fury of sustained protests for months. It subsided only after the then Prime Minister of India, Dr. Manamohan Singh, promised that the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) “…will be replaced by the more humane act”.

The AFSPA was closely scrutinized during the 2nd and 3rd periodic review of India by this committee. However, the Supreme Court of India upheld its constitutionality in 1997, and the Court ignored the request of this Committee to examine the Covenant compatibility of the AFSPA.

15 years later, following the first official visit of the Special Rapporteur on Summary, Arbitrary or Extrajudicial Execution, Prof. Christof Hynes observed that, “… he is unclear about how the Supreme Court reached such a conclusion … the powers granted under AFSPA are in reality broader than that allowable under the state of emergency as the right to life may effectively be suspended under the Act and the safeguards applicable in a state of emergency are absent.”

Further, Babloo pointed out that India’s present report (in paragraph 83) claims that “In genuine instances the Government of India has accorded sanction for prosecution”. This is simply not true, as both the EEVFAM and the HRA petitioned to the Supreme Court of India to seek justice for the 1,528 cases of extrajudicial executions. As a first instance, a Special Investigation Team of the Central Bureau of Investigation (SIT/CBI) registered 39 FIRs, with 36 Final Reports submitted. While criminal trials have commenced in cases involving the police; all cases involving the Armed Forces of the Union prosecution sanctions are denied under section 6 of the AFSPA. Even when clear prosecutable evidence is laid out by the premier investigating agency, the Union Home Ministry always denies prosecution sanctions.

“We request the Committee to pronounce the AFSPA as incompatible with the Covenant both in law as well as in practice,” Babloo drew the attention of the UN Human Rights Committee.

Regarding the ongoing violence in Manipur for more than 14 months, the human rights activist Babloo Loitongbam said, “Since the 3rd of May 2023, Manipur has been consumed by unending cycles of violence, with at least 230 reported deaths and counting. 13,247 infrastructures, including residential homes and religious places of worship, have been gutted and destroyed; leaving more than 60,000 displaced people to be interned in cramped relief camps, without adequate aid and life support systems.”

When the Central Government announced the direct handling of law and order in Manipur, and appointed a Security Advisor from the 4th of May, this was followed by the rush in substantial additional troops, which brought the hope that violence would be contained. Instead, this gave violence a new lease of life as armed militant groups, under the Suspension of Operation (SoO) agreement or outside of this arrangement, utilised the opportunity to don the role of the saviour of their respective ethnic communities. The indifference of the armed forces actively increased the death toll of civilians, and the cycles of raids and counter raids against the civilian population. And therefore, this is a violation of all human rights and humanitarian norms, which has intensified this crisis, Babloo told the Committee.

The ensuing climate of ethnic hatred accompanied by the ghettoisation of the warring communities in their areas of dominance, has practically snapped all ties of coexistence.

In the meantime, the Government of India along with the Government of Manipur, continue to promote an end to the violence, the reconciliation between warring ethnic communities, and restoration of normalcy, while taking no visible measures to stop the violent conflict or to heal festering wounds.

Individual citizens of Manipur – irrespective of gender, age, religion or ethnicity – have been robbed of their most basic human rights, as the Government of India systematically abdicated its Responsibility to Protect the population.

“We request the Committee to formulate an appropriate recommendation in line with the State obligation under the Covenant, read with the other relevant principles of international law,” Babloo said.

After hearing the statements made to the UN Human Rights Committee by the Indian State party, one Committee Expert said, “India was a victim of terrorism but had not officially declared a public emergency. Thus, the State party could not take measures that derogated from Covenant rights. The Supreme Court had issued judgements that brought into question the compatibility of legislation on the use of force by the police with the Covenant. Police officers and members of the armed forces could open fire on all persons suspected of a crime. The National Security Act allowed for the detention of persons considered to be a security risk without charge or trial for up to one year.

The Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act allowed for detention without charge for up to two years, without family visits. Extensive power had been granted to executive bodies to investigate and seize property based on suspicions of terrorist activities. It seemed that non-derogable rights were being violated by counter-terrorism laws. How were these compatible with the Covenant? Since the enforcement of the Public Safety Act, there had not been a single prosecution of members of the armed forces, although there had been over 1,500 complaints of human rights abuses by armed forces personnel. How was the State party ensuring accountability for the armed forces? What amendments would be made to counter-terrorism laws to ensure compliance with the Covenant? There were reports of human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings and sexual violence, in Manipur. How was the State party addressing the situation in Manipur?

The Indian delegation responded, India had a wide range of training institutes, including 350 institutes for training police officers. There were several public institutions working to address the situation in Manipur, including committees assessing violence against women in the region. The violence in Manipur was rooted in historic divisions. The State party was committed to addressing this violence in collaboration with civil society.

India had been a victim of State-sponsored cross-border terrorism for decades. All anti-terrorism laws had built-in accountability mechanisms. There was no immunity for the armed forces. Procedural action was taken on all complaints against the armed forces. The law provided for bail for persons detained under anti-terrorism laws, which was decided on by the courts.

However, in the Follow-Up Questions by Committee Experts, a Committee Expert asked how the State party monitored pre-trial detention implemented under the National Security Act and the Public Security Act. The Committee noted a problem with compliance with the decisions of the Supreme Court by the executive and legislative branches. In August 2023, the Supreme Court expressed displeasure in delays in recording reports of communal violence in Manipur. In March 2024, the Supreme Court set up a committee to oversee efforts to prevent violence in Manipur, but reports of such violence continued. Why was there a lack of compliance with the Supreme Court’s rulings?

A Committee Expert asked what the delegation meant when they said that the National Human Rights Commission had “disposed” of 3,000 cases of rights violations. What sentences had perpetrators of such violations received and what reparations were provided to victims? The Government was providing most of the budget of the National Human Rights Commission. Did this give it a say in the Commission’s activities?

In response to these questions, the Indian Delegation said that India had enacted legislation to deal with the menace of terrorism. This legislation ensured a balance between the liberty of citizens and the security of the State. Under the Public Security Act, all detentions made were shared with the Government and an advisory board reviewed them periodically. Arrested persons needed to be informed about the grounds of the arrest, and investigations needed to be completed within 90 days, or up to 180 days after extension. The constitutionality of the Act had been confirmed by the Supreme Court. More than 100 armed forces personnel had been punished for human rights violations, including two life sentences. Police were also held accountable for violations in court.

Tushar Mehta, the Solicitor General of India, told the UN Human Rights Committee that Manipur had an ethnic conflict that had spanned several decades. There were a few instances of rape and other sexual offences in the region, but the problem was not widespread. The Government had put together special investigation teams headed by senior officials from outside Manipur to investigate these instances. It had also mobilised Central Forces to assist Manipur State Police to address the situation. All cases for trial were transferred outside of Manipur. The Government was fully cooperating with the committee on the situation in Manipur, which had found interference by non-State actors in Manipur. There had been a large voter turnout in Manipur in the most recent elections.

Further, a Committee Expert said that the situation of refugees and asylum seekers had deteriorated recently. These persons reportedly had limited access to health services, jobs, education and housing. Undocumented migrants were reportedly placed in detention indefinitely. Authorities in Manipur had reportedly deported 38 Rohingya refugees to Myanmar, and there were plans to deport another 5,000 refugees. Did the State party plan to adopt a law that would provide procedural guarantees to asylum seekers? Would it suspend deportations of the Rohingya to Myanmar?

The Indian Delegation responded that India was not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention. Deportations followed India’s legislation on asylum. The Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019 protected the rights of persecuted minorities and defined criteria for citizenship pathways. The law aimed at fast-tracking access to citizenship for minority groups from six countries. It did not take away the citizenship of any person. Existing pathways to citizenship for persons from other countries had not changed.

In Follow-Up Questions by Committee Experts, a Committee Expert asked, Could the delegation provide the report commissioned by the State on the violence in Manipur to the Committee?

The Indian Delegation responded, “The report on violence in Manipur included sensitive information; it was currently being assessed by the Supreme Court and thus could not be published.”

1 thought on “UN Committee Grills India on Manipur; Dismisses India’s Claim Large Election Turnout is Sign of Normalcy”

White lies of BJP Government. Manipur is not in BJP’S map of India. Manipur is not part of India according to Modi. 10 times Presidents rule stated by Modi. Was those President’s Rule for Political turmoil/instability or Communal riots. Liars habituated in telling lies

Comments are closed.