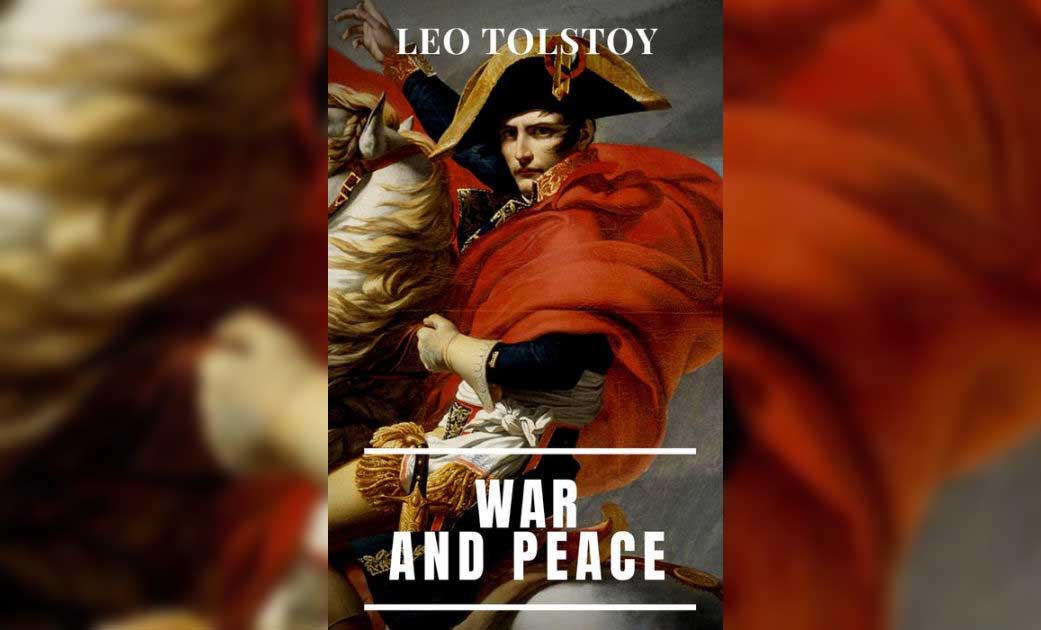

Set in 19th century Europe in the backdrop of the rising reign of the French dictator, Napolean Bonaparte, Leo Tolstoy negotiated a beautiful convergence of fiction and non-fiction to pen this timeless novel called ‘War and Peace’, the story of families and their relations with each other, navigating between the trepidations of war-torn Russia.

Tolstoy has a very clever style of writing, the thin line between fiction and non-fiction is hardly discernible in his words, and yet this seamless connection between these two genres never once distorts or confuses the narrative. Indeed, every work of fiction he has written is set against the backdrop of historically accurate events. A beautiful flaunt of genius! Speaking from my personal experience, the history that I learned from school textbooks could not measure up to the history I learned from War and Peace. When Battle of Austerlitz is mentioned, I will remember not only what year it was fought or who won the battle, and all such other textbook knowledge, but also vivacious imageries of those down-spirited Russians with depleting hopes for victory. I could actually feel my heart sinking when Kutuzov in low spirit predicted defeat for themselves seeing the lack of fighting spirit among the masses. Similarly, I felt a rush of excitement reading of the throngs of soldiers retreating back when caught in the eye of the hurricane. The most memorable of these visuals of Austerlitz would be the one with Prince Andrei Bolkonsky lying on the battlefield half-conscious, clutching to the Russian flag with the last bit of patriotism he could muster, as life waned in him, watching Napolean and his men tend to him in a show of magnanimity. It stuck in my mind how from the point of view of Prince Andrei, Napolean who was on his horse looking down upon him seemed so insignificant and mortal against the backdrop of the seemingly mighty serene and heavenly sky. This moment seemed to be a significant moment where Prince Andrei was on the edge of attaining spiritual peace; this moment was the decisive moment of his journey to enlightenment. In this imagery, Tolstoy seems to have inserted his own thoughts about how when we take a step back and look at humanity with a clear and unbiased mind, just how meaningless and foolish these wars that ignorant men have plagued each other with in comparison to the vast powerful and mysterious universe.

Same goes for the Battle of Borodino, the battle may have not meant so much to me and I might have forgotten about it with the passage of time had I read about it only in a history textbook. “When was the battle fought?” “Who won? Who lost?” “What were the economic and social consequences of the battle?” These are the questions often asked in textbooks, and they are facile and dry. Going through the experience of reading this book, I’ve come to discover the complex sides of war, it is not just about who won and who lost, nor the question of which side was good and which side was evil. These are not distinct and simple questions meant to elicit black and white answers; like every matter and subject in life, it comes in vast multitudes of colours and aspects. No textbook could have laid it out in such nuanced detail of desperation with which the soldiers fought for their land. But narrative is not in a single layer. Beneath these overt battles, I also got to see hints of more layers of the internal conflicts between the higher officials; the surge of patriotic spirit in the Russians as the French closed in on Moscow; the disgust and trauma of the very act of killing even if those they killed were ‘enemies’; the callous indifference they developed even at witnessing gruesome sights of fallen comrades.

Furthermore, the Battle of Borodino as narrated by Tolstoy also gave me a sense that winning a physical war against a numerically superior army has to begin with a victory on the moral and spiritual ground. Why such a result? It is unprecedented that an army that suffered more losses than the other side, prevailed to outlast and ultimately win the war. Tolstoy attributed this fact to the spirits of the army, of the citizens, of all Russians. The inherent patriotism instilled in every Russian was what fuelled the soldiers to fight without any fear for defeat, but overwhelmed by a determination to protect their homes. It also resulted in civilians leaving the capital in unison, burning the hays and food for livestock as they retreated so that the French will not benefit from them, and ordinary people partaking in guerrilla warfare. This said surge of spirit and strength among the patriots is not a feeling uncommon. It is somewhat inherent in human nature that we become aggressive and relentless on standing our territorial ground when our lands, homes, communities and families come under threat; this is when we begin to put all our strength and spirit in the fight, much of which we never knew existed. This is when we begin to see a win as a victory for the ages, and a loss as the ultimate humiliation, therefore we begin to prefer being martyred than losing. Likewise, the Russians, feeling endangered by the French trespassing on their homeland, brought out a vigorous flame from within them, further ignited by the repulsive thought of the French invaders plundering their homes, taking their women and children, and pulling down their flag to hoist theirs.

Another aspect of this novel that I am very much fond of is how balanced it is. Tolstoy was not an emotional writer who, led by his patriotic feelings for Russia, wrote volumes about the grandeur of the Russian Empire and painting the French as bandits, ruffians and savages. His words were as rational as they can be, written from the point of view of the Russians and French both. He further did not shy away, disregarding the possibility of being denounced by Russian fanatics, from criticising the Russians where criticism is just. Writing from the point of view of the French, Tolstoy humanised the soldiers, in my opinion a feat that most ‘historical writers’ would not do, as he made us visualise the reluctance and almost delirious horror with which the French carried out executions of the prisoners, how they were on friendly terms with the prisoners they grew acquainted with etc. Tolstoy simply did the task of not letting us forget that they too were flesh and blood humans, acting out their duties for their own homeland just as the Russians were acting out for theirs.

It is interesting to note that Tolstoy did not portray only the dark side of wartimes of the period but also put in just as much effort in telling the stories of the common folk and their endless efforts to work through the looming darkness of war and carry on with their lifestyles as normal as possible. It was a pendulum swaying between the war and the peace, or rather the search for peace. The families and their parties, soirees, courtships, marriages, and family bonding, gave the readers a taste of the life of Russian gentry and their society. However, Tolstoy believes neither victory in war nor the lavishes of life is what is called ‘peace’. Instead he believes spiritual peace, obtained through an unmaterialistic life, free from greed and contempt, as the authentic peace. In this belief, he has hinted his dissent for Capitalism and the wave of materialism it has brought along. However, it should be kept in mind that Tolstoy was not a Communist, rather he identified himself as an Anarchist.

There is one aspect of this great classic that I found disconcerting and this is Tolstoy’s degrading portrayal of women. It may be argued that the author was merely representing the current societal thoughts and beliefs at that time to assume its historical accuracy and credibility. Hence, Tolstoy would often portray the female characters in his book as shallow-minded, superficial, and obedient wives etc., contrasting with his portrayal of men as strongly opinionated, stern husbands etc. Instances presented themselves, where the writer’s own perception of women folks reflected on his choice of words, which appeared awkward and derogatory to a 21st century reader. This perception of Tolstoy can be attributed to his own theory that he propounded in this novel, that a character does not come out from vacuum; circumstances make a character, make a man and in turn, events. Tolstoy was raised and brought up in 19th century Russia when, just like everywhere else in the world, women’s rights weren’t considered human rights and women simply accepted it as fate and that it was to be as it should be. Growing up and living in these circumstances of patriarchal dominance, rich with the notion of women being subservient and inferior to men, it is no wonder that there is also a sexist side even in a character like Tolstoy.

Overall, the book is a delightful piece of art from which one can take away a rich experience of history. To sum it up, “War and Peace” is a grand vision dedicated to the rawest form of history of war, and how even in the middle of the chaos of war, there is always an enduring longing of mankind for peace.

The writer is an undergraduate student of history, Maitreyi College, Delhi University