The recent announcement on 9 November by junta-installed president of Myanmar Former General U Myint Swe sent an unusual alarming message across the nation, the imminent threat of Myanmar breaking apart if the military fails to crush a joint offensive by ethnic armed groups fighting in Shan State bordering China. This was followed by another development on 20 November; the report indicates Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military showing signs of a notable decline with rebel forces having captured more than 8,000 square kilometers, nearly half of the nation. Earlier in September 2021, the National Unity Government (NUG), a shadow government in exile emerged. NUG started the defensive war against the state military with the creation of militias targeting the junta and its economic base. The Ethnic Arm Organisations (EAOs) of Myanmar have been fighting the Tatmadaw for decades and some of the armed ethnic groups have in recent times coordinated with the NUG militias to overthrow junta.

The three ethnic armies namely the Kokang’s Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), a majority Han Chinese ethnic, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Palaung, or Ta’ang, people and the Arakan Army (AA), the Rakhine people with large migrant population in the east of the country helped to establish the Arakan Army, now one of the best-equipped forces in Myanmar, started operation 1027, and got the name operation 1027 because it was launched on October 27. The formidable Three Brotherhood Alliance was formed by these three EAOs as a result of the coordination activities and in order to fulfill their ambitious territorial expansion in Myanmar.

In the present conflict China did not give any restraining order to the Myanmar ethnic armed groups operating along the border with China. The estimate loss of US$40 billion on online scam angered the Chinese on the junta’s inaction.

The conflicts in Myanmar are leading to an emergence of new geopolitics. Mention may be made of Myanmar, a country in possession of vast natural resources marred with civil unrest and instability since 1 February 2021 coup. Myanmar is an ideal battleground of China and America. The ethnic armies namely the Karen, the Kachin, the Karenni and Chin allied with the National Unity Government (NUG), which was set up by the elected administration that was deposed by the coup. The various others armed ethnic groups operating in Shan State bordering China and Thailand did not ally with NUG. The various People’s Defence Force (PDF) groups across the country have aligned with well-organized armed groups, such as the Three Brotherhood Alliance.

The fall out of junta is well narrated in the article written by Ronan Lee titled, “Myanmar’s military junta appears to be in terminal decline”, published in ‘The Wire’ on 19 November 2023. Ronan Lee gives insightful information on China’s role and Post-junta planning in Myanmar as follows:

China’s role

Brotherhood Alliance members are themselves territorially ambitious, but rely on China for arms so it is unlikely an operation in China’s hinterland could have occurred without China’s acquiescence. Allowing this operation to go ahead is a strong statement by a Chinese government frustrated with the junta’s inaction on online scam centres in Shan State where thousands of trafficked Chinese and other foreigners have been forced to work in slave-like conditions.

China’s strategic ambiguity is unsurprising. China was far from enthusiastic about the 2021 coup. China’s ambassador to Myanmar, Chen Hai, told journalists at the time a coup was, “absolutely not what China wants to see”. While traditionally a key international ally of the junta, China’s leadership had a very close relationship with Myanmar’s ousted de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and maintains close ties with many of Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups.

Now, strategic reversals, nationwide territorial losses and economic decline mean momentum has strongly shifted away from Myanmar’s junta. China’s leadership may have read the situation better than most, recognising the junta may now be in a death spiral.

Others have been less shrewd. Russia has displaced China as the junta’s biggest arms supplier accounting for US$406 million (£326.5 million) of Myanmar’s arms imports since the coup and crucially providing aviation fuel in exchange for funds, access to Bay of Bengal port facilities, and regional relevance.

Coup leader Min Aung Hlaing recently welcomed Russia’s navy for joint manoeuvres, describing Vladimir Putin in glowing terms as a “leader of the world who is creating stability on the international arena”. For Putin, this may soon be embarrassingly unwelcome praise. By linking itself so closely with a declining junta, Russia guarantees its Myanmar influence and regional relevance will not outlast military rule.

Post-junta planning

The NUG idealises a post-junta Myanmar unified under its leadership with Aung San Suu Kyi returned to power. But for many ethnic armed groups – who will feel they, rather than the NUG, inflicted the strongest blows on the junta and now control significant territory – that is not likely their preferred outcome. They will seek guarantees about key demands around federalism and minority rights that were not satisfactorily addressed when Aung San was last in power.

The junta appears on a clear path to defeat, but this will not be immediate. Meanwhile, the state’s military forces commonly respond to reversals with shocking violence, so bringing junta rule to a speedy end must be prioritised. Myanmar’s population and neighbouring states will also not want the country, post-junta, to descend into the same sort of fractured instability as in the immediate post-independence period.

Myanmar’s neighbours, ASEAN, and western powers who have talked tough on human rights in Myanmar, including the US, UK and EU, must now take steps to ensure the post-junta future plays out peacefully with all resistance groups included in decisions about Myanmar’s future.

The transitional period after the removal of the military will require a commitment from international actors to ensure the stability of the country, perhaps like the Cambodian UNTAC process in the 1990s. Rather than being again caught on the hop by events in Myanmar, ASEAN and the UN should begin preparations to manage the transition to a post-junta Myanmar that now appears increasingly likely.

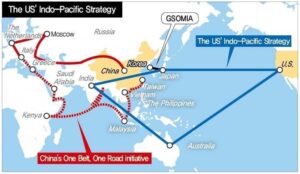

The Map of US’ Indo–Pacific Strategy shows the drawing of Quad consisting of four members namely Australia, India, Japan and the United States. The four Quad members have played a major role in purposefully redefining the “Asia-Pacific” as the “Indo-Pacific”, to deepen trans-regional ties between the Indian and Pacific Ocean areas, and to, in their words, deal more effectively with the rise of China, the Middle East and Africa

India’s troubled borderlands

China had been the dominant power in East Asia for centuries before the arrival of Western imperialism in the nineteenth century. United States sees China’s hegemony in Myanmar. The Indian government is sounding the alarm about what the repercussions would be in the increasing turmoil in Myanmar borderlands with India. This calls for more vigilance in the northeastern states of Manipur and Mizoram. There is a strong possibility that China could play a major role in influencing the EAOs of Myanmar post junta. Earlier India had boundary issues with China in Ladakh and in the states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh..

The United States and European Union’s had an ulterior motive to depose junta after 2021 coup. They even imposed economic sanctions on Myanmar government and the high ranking military regime officials. The aim of western allies is to install democratic elected government thereby curbing the growing influence of China’s rising graph in the global economy and military scene. On the other hand China is well determined to dominate the strategic continent of Asia militarily, culturally, politically and economically. The Myanmar crises give the most needed impetus to China as serious challenger to emerging superpower status after United States.

As of today the China’s aggression on Myanmar is directed towards the consolidation of the invested projects. China and Myanmar trade relations grew from 1988 after western sanctions were imposed on Myanmar. On 5 August 1988, China signed a major trade agreement, legalizing cross-border trading and began supplying considerably military aid.

The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) is a number of infrastructure projects supporting connectivity between Myanmar and China. It is an economic corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The infrastructure development plan calls for building road and rail transportation from Yunnan Province in China through Muse and Mandalay to the seaport city, Kyaukpyu in Rakhine State. The transportation route follows gas and oil pipelines built in 2013 and 2017. At the end of the route, a port and Special Economic Zone is planned at Khaukphyu. The largest construction project along the route is the 431-kilometre Muse-Mandalay Railway, a project estimated to cost US$9 billion. The newly built railway would connect to the Chinese railway network at Ruili, Yunnan province.

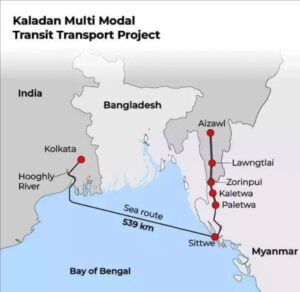

On the other hand India had invested in Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project passing through the Chin State of Myanmar.

Map of Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project

The Kaladan Road Project is a US$484 million project connecting the eastern Indian seaport of Kolkata with Sittwe seaport in Rakhine State, Myanmar by sea. In Myanmar, it will then link Sittwe seaport to Paletwa in Chin State via the Kaladan river boat route, and then from Paletwa by road to Mizoram state in Northeast India. All components of the project, including Sittwe port and power, river dredging, Paletwa jetty, have been completed, except the under construction Zorinpui-Paletwa road. Originally, the project was scheduled to be completed by 2014, but end-to-end project is expected to be fully operational only by December 2023 as per November 2023 update.

The route of the project around Paletwa is less than 20 km from the Bangladesh border and along the Kaladan river is troubled with Chin conflict, Rohingya conflict and militant groups such as Arakan Army and Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA).

The Kuki-Chin people inhabiting in Myanmar along the border with Manipur wanted to merge with India in the past. Maloy Krishna Dhar in his book, “Open Secrets India’s Intelligence Unveiled”, 2005, writes as follows:

“Kuki and Chin population of Burma living in the administrative units under Singgel, Sekshi, Pantha, Kuzet and Thygon often assisted them demanding merger of the Burmese Kuki and Chin areas with India. It was a dangerous move.

The Kukis and other allied tribes had originally migrated to Manipur from Burma at a point of time when hegemony of the Manipur kings often stretched up to the Kabow valley and the banks of Chindwin.”

In the changing political scenario in Myanmar the question now arises will India rethink on the earlier merger demands of the Kuki-Chin inhabited areas of Myanmar with Indian Union in the event of possible breakup? The serious poser to China is will it allow the Kachin and Chin EAOs the merger of Kuki-Chin inhabited areas of Myanmar to the Indian Union? The merger idea may not go down well with China taking into consideration the influence and dominance they want to exercise on the EAOs, particularly the Kachin and Chin EAOs. This merger if it becomes a reality in India it will have dangerous implications on the Meiteis of Manipur.

There exists a good relationship between the Kachin and the Chin ethnic, and they are good allies being predominantly Christians with the strong backing of the world churches. It was the Kachin Independent Army (KIA), who first trained the Chin rebels the use of firearms in Myanmar. The Kachin and Chin rebels have allied with PDF after the 2021 coup to overthrow junta. Meanwhile KIA had aligned with the Three Brotherhood Alliance in Shan State of Myanmar. The wind of change in Myanmar may even sway Kachin Independent Army, a strong ally of NUG and Three Brotherhood alliance towards China in the fast changing political environment. In the rightful saying the alliances made are meant to be broken in these prevailing circumstances.

As per the Reuters, November 14, 2023, the area of Khampat a town in Kabaw Valley in the Sagaing Region in western Myanmar came under the control of Chin rebels. The two camps next to India’s Mizoram State were also run over by the Chin rebels. The serious poser to National Unity Government post junta is will they be successful to bring all the EAOs allied with them under NUG banner to form the next government? The answers for all these questions only time will tell.

Now, looking back in the history of Manipur kingdom, the border issues with Burma (Myanmar) had always been the bone of contention leading to frequent wars. The role of Manipur kingdom figured as one of the factors in the events leading to First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26) and the Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885). The events leading to the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26) and the Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885) are recorded below as follows:

In the first quarter of 19th century, the Burmese royal book namely Royal Order of Burma (ROB) dated 8 March 1818, recorded a letter sent by Konbaung emperor Bodawpaya to Maharaja Marjit Singh to drive out the English from Manipur. Marjit ignored Bodawpaya’s plea. Grandson Bagyidaw succeeded Bodawpaya after his demise in 1819. Bagyidaw invited Marjit Singh to attend the coronation ceremony and Marjit’s failure to show up enraged Bagyidaw who under the command of General Maha Bandula invaded Manipur, Assam and Cachar. Manipur was brought under the Burmese rule for seven years (1819-1826), which is known as seven years devastation or chahi taret khuntakpa in Manipuri. Myanmar’s long ill-defined border with British India and Britain’s ambition of territorial expansion and consolidation of Southeast Asia culminated in the outbreak of First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26).

D.G.E. Hall in his book, “History of Burma”, recorded a second opportunity to settle relations occurred in 1882. It arose over the Kabaw Valley question, which was thought to have been settled by Burney in 1834, when the valley had been awarded to Burma. Unfortunately no precise demarcation of the boundary line with Manipur had ever been carried out. With Thibaw’s accession the Burmese fomented a series of frontier disturbances. The Government of India thereupon invited Thibaw to join in a frontier commission. When he refused, a British commission proceeded to mark out the frontier, and in doing so, requested the Burmese to withdraw an armed guard from a village which was claimed by Manipur.

In 1882, Thibaw sent an envoy to Calcutta. He was given a most favourable reception by Lord Rippon; but just when hopes of a friendly settlement were beginning to rise, King Thibaw suddenly recalled the envoy; and by that time, the British Supreme Government took up such a threatening attitude that in 1884 British reinforcements were sent in favour of the Raja Chandra Kirti Singh of Manipur. The frontier disturbances immediately ceased, but the hope for improvement in Anglo-Burmese relations faded out.

King Thibaw’s volte face over the Manipur negotiations seems to have been the result of a decision to resume relations with France. He knew that Britain had become extremely uneasy about French activities on the Mekong and their penetration into Annam and Tongking. He imagined that he could play off the French against the British. But it was unfortunate that it had never occurred to him, that in the dangerous world of power politics, in which he was living, his only chance of survival as an independent monarch lay in cultivating British friendship, and that an approach to France might force the British to depose him. Subsequently, these unfolding events led to the outbreak of Third-Anglo Burmese War (1885).

The border issues with any sovereign nations in the world need sensitive handling. The Manipur history recalls it in two earlier occasions leading to the outbreak of two Anglo-Burmese Wars. Any faulty border policies and wrong doing can have disastrous consequences. The current ethnic unrest in Manipur with Meitei–Kuki/Chin is nearing seven months and no concrete solutions have been brought forward by the centre government in dealing with the warring factions on a negotiating table to discuss peace. The present turmoil in Myanmar borderlands with India particularly Manipur state, the situation can further worsen if the influx from Myanmar is not stopped immediately and if the ethnic clashes issues are not resolved on war footing with utmost sincerity.

Manipur an Asiatic power with her military might in 18th century had a proud history of existence of more than 2000 years old kingdom. The Meitei people of Manipur are very firm and determined to this day on safeguarding and protecting the territorial integrity of the state and will not compromise ceding even an inch of her motherland.

The testimony of the bravery of Manipuri people is known when it comes to the protection of her territorial boundary. Nandalal Sharma in his book “Meitrabak” had mentioned Manipur King Puranthaba (r. 1247-63) and their army stationed at Manipuri boundary of the Chindwin River (Ningthee Turel) with preparation to defend their kingdom from the attack of the Tartar ruler Kublai Khan (the grandson of great Mongol king Genghis Khan). Ningthee Turel was the ancestral boundary and dividing marker between both the kingdoms of Manipur and Burma. According to the Burmese records the first Mongol invasion of Burma happened in the year 1277-87. It’s most likely Puranthaba’s successors Khumomba (r. 1263-78) or Moiramba (r. 1278-1302) must have been the one who acted.

During Kublai’s reign the whole of the Shan Sawbwaships included between Manipur and Annam (Vietnam), was at least nominally subject to the Mongol dynasty of China. The disintegration of the Shan kingdom of Nanchao opened up the way to Burma and led to the expeditions which resulted in the overthrow of the Empire of Pagan by the China Yuan dynasty.

The story of Tartars Mongol ferocity is found in the olden folklores of Manipur in the use of word “Tapta” derived from Tartar. In the Manipur folklore the non-stop weeping child suddenly remained silent when the mother mentioned the name “Tapta”.

It is high time India needs to intervene with the warring factions to end the seven months old conflict between the Meiteis and the Kukis. As we all know due to current ethnic unrest the state economy is 10-20 years lagging behind. The main priority of the government in the centre and the state is to generate opportunities to create wealth and give the masses healing touch to their wounds.

Finally, the main priority of the central and the state government today is to give assurances and commitments to the peoples on the restoration of peace and normalcy in the state at the earliest. Instill sense of security to the minds of the people so there are no restrictions on the free movements of the valley people to the hills and vice versa in the state. The return to the life which existed in Manipur before 3 May 2023, if it becomes reality once again only then people’s long prayers will be ultimately answered.

The writer is an independent researcher and author of “Vedic Imprint in Southeast Asia: With Special Reference to Manipur” and joint author of “The Political Monument: Footfalls of Manipuri History”. He is an MBA from Sydney, Australia and worked in Myanmar from (2013-16) in hydro and renewable energy space.