This essay attempts to put forth an analysis of certain historical and political events towards a better appreciation of Manipur’s distinctive historical and political status in relation to the Union of India and international law at large. The Asiatic State of Manipur which existed as an independent sovereign country before the arrival of colonial British became part of the Indian Union in 1949 through the contested Manipur Merger Agreement. A politico-legal analysis is carried out based on the historical and political facts surrounding the peculiar status of Manipur.

To drive home the point, an Instrument of Accession (IOA) was signed by Manipur’s ruler on August 11, 1947 which is purportedly said to have been accepted three days later by Mountbatten the then Governor-General of the Indian Dominion. Agreements such as the IOA were also signed by other Princely States formerly under the British suzerainty. The Ministry of States of the Dominion Government of India led by Sardar Patel and VP Menon was entrusted to complete accession to the Indian Dominion by the States before August 15, 1947, the date on which British paramountcy was appointed to lapse.

IOA was designed to be executed by those Princely States which had full power and jurisdiction over its subjects and territory. By Article 3 of the IOA, the rulers ceded to the Dominion Government of India three subjects namely defence, external affairs and communication. Excepting these three subjects, the States had full sovereignty in their internal administration. Article 7 provides that accession to the Dominion of India shall not have the effect of committing the Ruler to acceptance of any future constitution of India or fettering his discretion to enter into arrangements with the GOI under any such future constitution. Article 8 stipulated that the accession shall not affect the continuance of the sovereignty of the Ruler with respect to his State or the exercise of his powers, authority and rights including the validity of any law in force in his State. Under Article 5 of the IOA, the GOI cannot amend or modify Article 3 subject-matter jurisdiction unless such amendment is accepted by the Ruler through an Instrument supplementary to the IOA.

The policy objectives of IOA were strongly founded upon the Memorandum submitted by the Cabinet Mission to the Chamber of Princes on May 12, 1946. The freedom to enter into either federal relationship or particular relationship with the Government of India by the States was envisaged in Paragraph 5 of the Memorandum. Read with Section 7 (1) (b) of the Indian Independence Act, 1947, it re-affirmed the restoration of sovereign independence of the States.

As regards, the legal consequences of acceding to the Dominion Government of India by way of the IOA by the then Manipur’s ruler, provisions of the Manipur State Constitution Act, 1947 (MSCA) which came into force on July 26, 1947 are pertinent to take note. Section 9 (b) of the MSCA placed Manipur’s ruler as the nominal constitutional head of the State (read independent country). He did not have executive authority as it was vested upon his Council

_________________________

of Ministers by virtue of Section 10 (a). Being a nominal head, he could not alone accede to such an instrument where the legitimate interest of Manipur’s administration was involved. The Maharaja’s prerogative was limited in this context by Section 8 (a) of the MSCA. Section 18 of Manipur Constitution required 75 percent votes of the total members present and voting of the Manipur National Assembly on any such matters involving the Government and well-being of the people. These legal analyses equally apply to that of the Merger Agreement as well. No historical evidences exists which suggests that Manipur’s National Assembly had ratified the IOA of 1947 or Merger Agreement of 1949.

Matters which concern the political future of a people are not by conventions and State practice decided by mere putting of signatures of the rulers. United Nations General Assembly resolution 2625 (XXV), 1970 recognises the ‘free’ association or integration principle with an independent State as one of the modes of implementing the right of a people to self-determination. The requirement to hold a plebiscite is grounded upon this philosophy. This principle has been universally accepted and become an established norm of exercising by a people of their right of self-determination. Therefore, in such a context ratification or non-ratification of IOA or Merger if any becomes a non-issue here. The Dominion Government of India acknowledged the significance of this right when it allowed holding referendums in Junagadh and Pondicherry in 1948 and 1954 respectively. The GOI did not consider important to allow peoples of Manipur, Tripura, Hyderabad, Travancore, Jammu & Kashmir, etc. to freely determine their own political future. As evidenced from the coercive nature of obtaining the signature of Manipur’s King on September 21, 1949 at Redlands, Shillong and consequential dissolution of the popularly established Government of Manipur and her National Assembly on October 15, 1949 unilaterally by the Government of India, the Indian Dominion violated Article 2 (4) of the UN Charter. Before the coming into force of its own Constitution, India violated UN Charter obligations and which commitment it incorporated under Article 51 (c) of its own Constitution of 1950. The political destiny of a people is not something which can be traded by signing an instrument or even through ratification by a legislature without the consent of the people concerned. Manipur National Assembly denounced on September 28, 1949 the nullity and unconstitutionality of the Merger Agreement. Nor did the people of Manipur hold a referendum to integrate with India. Recently, the people of Manipur in 1993 reaffirmed its denunciation of the illegal and unconstitutional character of the Merger Agreement.

In the light of such historical and political circumstances as evidenced from various State records, treaties and agreements including the White Paper on Indian States of the Ministry of States, Government of India, New Delhi, 1950, the taking over of Manipur’s administration by the Government of India stipulated in Article 1 of the Merger Agreement constitutes occupation of the former by the latter from the standards of international law, jurisprudence established by the UN and State practice. Article 1 of the Merger Agreement confirms India as an administering State (read power), having responsibility towards Manipur’s well-being and administration. Thus, according to International humanitarian law particularly Article 43 of the Fourth Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War on Land, 1907 India’s position with respect to Manipur is that of an occupying power.

INDIA’S HISTORICAL RESPONSIBILITY TOWARDS MANIPUR

This accidental integration of Manipur into the Indian polity and the consequences it entailed attracts India’s state responsibility more seriously towards the protection of the historical and political status of Manipur and its people today. India’s historical responsibility towards Manipur is couched in the language of the Manipur Administration Order (MAO) dated 15th October 1949 issued by the then Chief Commissioner who was appointed by the Dominion Government of India. More than Entry number 19 of the First Schedule of the Indian Constitution which had sought to define Manipur as its 19th state, this order established the legal and political fact of the status of Manipur. MAO testifies how the GOI established its authority over Manipur and her people. Politicians, bureaucrats and academics alike should be able to put forth this naked truth and remind the GOI of its historical and political responsibility which it owes towards Manipur and her people since 1949. Such a premise can courageously guide any attempt to negotiate with the GOI towards protection of Manipur’s identity in all respects including historical, political, cultural and mutual co-existence of her people.

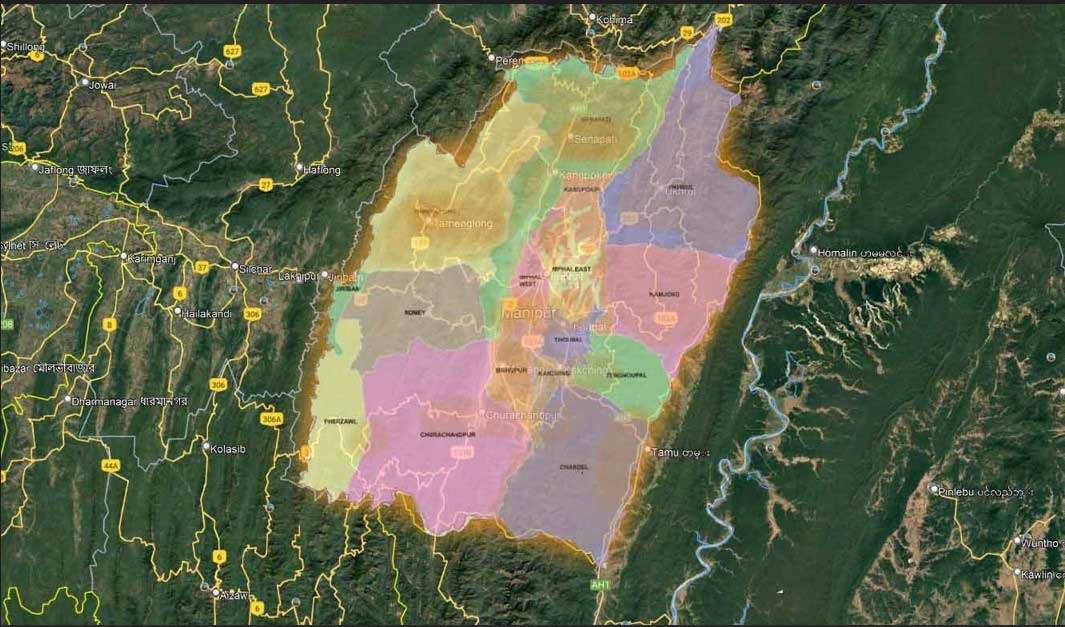

India’s historical responsibility towards Manipur is continuing in character. The people of Manipur do not recognise Section 3 of the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 in so far as it sought to establish Manipur as a ‘new’ state under the Union of India. New Delhi’s theory of the establishment or creation of the state of Manipur anew in 1971 amounts to annexation of the state in so far as it sought to officially incorporate Manipur as 19th state of the Indian Union. It is not recognisable as it seeks to obliterate Manipur’s existence as a historical and political entity pre-1949. Article 2 (4) of the UN Charter, Principle 1, paragraph 10 of the UN GA resolution 2625 (XXV), 1970 and jurisprudence of the international tribunals rendered in such cases as the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Rep 136, 2004, etc. qualifies acquisition of territories through the use of force as illegal in international law. Manipur’s statehood in 1972 is no more than a mere legal fiction of India’s statecraft. Manipur did not come into being by virtue of Articles 2 and 3 of India’s constitution nor by the 1971 (Reorganisation) Act. The White Paper on Indian States, 1950 in its Appendix XLIII titled ‘Statement showing the area and population of States which have merged with provinces of India’ which shows the total area of Manipur as 8, 620 (eight thousand six hundred twenty) square miles at the time of the contested merger is another pointer towards this. Manipur’s existence as a historical and political entity before the establishment of the Indian republic is not a legal fiction created by India’s constitution. Manipur Administration Order, 1949 testifies this facticity. This order read together with the resolutions adopted by the Manipur National Assembly on September 28, 1949 and the National Convention on Manipur Merger Issue on October 28-29, 1993 also nullifies the applicability to Manipur as a State which participated of her own free will into the making of the idea of India as a “Union of States” as defined in Article 1 of its constitution.

UTI POSSIDETIS JURIS AND MANIPUR

Article 43 of the Fourth Hague Convention, 1907 limits the authority of the Indian State to apply or impose Article 3 of its constitution to Manipur in so far as it is assumed that it can modify the existing territorial integrity of the state to accommodate ethnic aspirations. The jurisprudence of uti possidetis juris stands to reinforce India’s historical responsibility towards Manipur’s inviolable political status. The principle of Uti possidetis juris firmly developed in the jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice in the Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali protects the original state of national integrity, not only in terms of territoriality but also the organic character of Manipur’s polity, society and culture at the time of independence from British rule. Uti possidetis juris in the words of the ICJ meant the ‘photograph of the territory at the critical date’. It informs that administrative units of the same colonial power respect the territorial boundaries of one another at the time of achieving independence. Overlapping claims over Manipur over its territory is unfounded in international law. The Government of India as a successor State to British Empire did not have well demarcated boundary. The Government of British India was confined to the territories of British provinces excluding the territories of Princely States. Whereas the political entity called the Union of India was established as an outcome of British colonialism, the Princely States’ existence as historical and political entities were independent of remaining as Protectorates under British suzerainty. Hundreds of treaties, agreements and Sanads testify this. There were no India as a united political entity as it is today before the arrival of the British East India Company in 1600 AD. As such the existence and legal personality of the States were not derived from any entity including the British Empire.

As such, Manipur’s territorial boundary as existed during from the British colonial rule at the time of its lapse is protected by international law. The Chamber of the ICJ stated in the Burkina Faso/Mali case thus “the principle [of uti possidetis juris] is not a special rule which pertains solely to one specific system of international law. It is a general principle, which is logically connected with the phenomenon of the obtaining of independence, wherever it occurs. Its obvious purpose is to prevent the independence and stability of new States being endangered by fratricidal struggles provoked by the challenging of frontiers following the withdrawal of the administering power”. This was reaffirmed by the Arbitration Commission concerning Yugoslavia and Macedonia when in its Opinion No. 3 stated

“All external frontiers must be respected in line with the principle in the United Nations Charter, in the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations (General Assembly Resolution 2625 (XXV)) and in the Helsinki Final Act, a principle which also underlies Article 11 of the Vienna Convention of 23 August 1978 on the Succession of States in Respect to Treaties”.

The fundamental purpose of the uti possidetis juris principle is to ensure stability of territorial boundaries of States so established at the time of independence from colonial rule.

MANIPUR’S TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY AND INTERNATIONAL LAW

The boundaries of Manipur were recognised by treaties and State records. The inviolable character of Manipur’s territorial boundary is derived from the principles of international law. The principle of stability of boundary is reinforced by a consequential principle known as objectivization of boundary treaties which states that once boundaries have been established or confirmed in an international agreement, an objective reality has been created which will survive the demise of the treaty itself. The ICJ reaffirmed this principle in the context of the 1955 Treaty between Libya and France concerning the boundary between the former and Chad claiming through the latter. The court declared:

“the establishment of this boundary is a fact which, from the outset, has had a legal life of its own, independently of the fate of the 1955 Treaty. Once agreed the boundary stands, for any other approach would vitiate the fundamental principle of the stability of boundaries, the importance of which has been repeatedly emphasised by the Court. A boundary established by treaty thus achieves a permanence which the treaty itself does not necessary enjoy. The treaty can cease to be in force without in any way affecting the continuance of the boundary … but when a boundary has been the subject of agreement, the continued existence of that boundary is not dependent upon the continued life of the treaty under which the boundary is agreed”.

The 1835 Treaty concluded between Gumbheer Singh and British Commissioner F.J. Grant establishing Manipur’s boundary is a case here. It recognises Manipur’s territorial demarcations. Article 1 established eastern bank of Jeeree as Manipur’s western most boundary between British and Manipur. Article 6 recognized the Ningthee or Khyenween river (Chindwin river) as the eastern most boundary of Manipur. A boundary established by treaty thus achieves a permanence which the treaty itself does not necessary enjoy. The treaty can ‘cease to be in force without in any way affecting the continuance of the boundary … but when a boundary has been the subject of agreement, the continued existence of that boundary is not dependent upon the continued life of the treaty under which the boundary is agreed’.

As per the 1950 White Paper on Indian States of the GOI, the total territorial area of Manipur at the time of the contested Merger Agreement was 8, 620 square miles. However, as per the Proclamation of Maharaj Bodhchandra while inaugurating the first sitting of the Manipur National Assembly on October 18, 1948, Manipur’s total geographical area stood as 8650 square miles plus 7000 square miles of the Kabaw Valley including 7900 square miles of the hills of Manipur. The demarcation of Manipur’s boundary as reflected in the 1835 Treaty seems to corroborate Manipur’s total area mentioned by the Maharaja on October 18, 1948. The 1834 Agreement regarding Compensation for the Kubo Valley concluded between the British and Burmese Commissioners confirmed the amount of compensation to be paid to Manipur for transferring the valley to Burma which was fixed at 500 sicca rupees at the time (Article 1). As per the Proclamations of Maharaja Bodhchandra of 1948, the amount of the annual compensation stood at Rs. 6, 270/- which ceases to come today to the exchequer of the Government of Manipur mysteriously.

Amidst issues and claims of losing sizeable portions of her territory, after integration with India, the present territorial boundary of Manipur is protected by the 1835 treaty. Article 62 (2) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 protects Manipur’s boundary as established by the 1835 treaty. The lapse of all treaties and agreements as a consequence of the setting up of the new Dominions under Section 7 (1) (b) of the Indian Independence Act, 1947 does not affect Manipur’s boundary established by treaties concluded between the British and Manipur in 1835. The principle of rebus sic stantibus does not affect the permanence of boundaries established by the treaty while the treaty in question may itself lapse or expire. The International Law Commission’s Commentary reaffirmed this position stating that such treaties should constitute an exception to the general rule permitting termination or suspension, since otherwise the rule might become a source of dangerous frictions.

The clean slate principle incorporated by Article 16 of the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties 1978 does not apply to boundary treaties. Waldock in his report stated:

“the weight both of opinion and practice seems clearly to be in favour of the view that boundaries established by treaties remain untouched by the mere fact of a succession. The opinion of jurists seems, indeed, to be unanimous on the point even if their reasoning may not always be exactly the same. In State practice the unanimity may not be quite so absolute; but the State practice in favour of continuance in force of boundaries established by treaty appears to be such as to justify the conclusion that a general rule of international law exists to that effect”.

This approach which states that boundary established by treaties are not affected by succession of States is accepted by the International Law Commission and by governments and ultimately in Article 11 of the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties which provides that ‘a succession of States does not as such affect a boundary established by a treaty…’.

The continuity of boundaries established by treaties had been reaffirmed by the ICJ in the Tunisia/Libya case, incorporated in the 1978 Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties while the Arbitration Commission established by the International Conference on Yugoslavia stated in Opinion No. 3 that “all external frontiers must be respected in line with the principle stated in the United Nations Charter, in the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations (General Assembly Resolution 2625 (XXV)) and in the Helsinki Final Act, 1975 a principle which also underlines Article 11 of the Vienna Convention of 23 August 1978 on the Succession of States in Respect of Treaties”.

Another ground for exception to this clean slate rule is the requirements of the international community with regard to the maintenance of international peace and security. Francis Vallat, the Special Rapporteur in 1974 stated that acceptance of the idea that a bilateral boundary treaty could be swept aside by a succession of States ‘would result in chaos’ and was ‘unthinkable’. The disturbance of existing boundaries is much more likely to create chaos than their maintenance. Such positions have been reaffirmed in the Argentine-Chile Frontier case. The ICJ stated in the Libya/Chad case, ‘once agreed, the boundary stands, for any other approach would vitiate the fundamental principle of the stability of boundaries’. Judge Shahabuddeen put this

“the principle of the stability of boundaries, as it applies to a boundary fixed by agreement, hinges on there being an agreement for the establishment of a boundary; it comes into play only after the existence of such an agreement is established and is directed to giving proper effect to the agreement. It does not operate to bring into existence a boundary agreement where there was none. The special rule of interpretation of treaties regarding boundaries is that it must, failing contrary evidence, be supposed to have been concluded in order to ensure peace, stability and finality. The presumption is that courts will favour an interpretation of a treaty creating a boundary that holds that a permanent, definite and complete boundary has been established.”

Thus, Manipur’s territorial boundary and both territorial and non-territorial integrity are protected under international law. Those having counter-claims have to base their hypothesis on historical records, treaties and agreements, authenticated state records and principles of international law. The GOI under the principles of international law discussed above is prohibited from dismembering the historical integrity of Manipur. The creation of the states of Nagaland, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and those of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Telangana under Article 3 of India’s constitution does not stand the test of legality in the context of Manipur. Ethnic aspirations for homeland or establishment of an entirely new independent country fail to disturb Manipur’s boundary. Manipur was not a creation of either the British or the India’s constitution like Mizoram or Nagaland.

CLAIMS OF UNIFICATION ON THE BASIS OF ETHNICITY

In the light of peculiar status of Manipur’s integrity as protected by international law, claims made by ethnic communities over the territory of Manipur on the basis of ethnicity, historical connexion and cultural affinities are not sustainable under international law. Manipur, Burma and Bangladesh (formerly east Pakistan) were all under the suzerainty of one common colonial power. Renowned international law scholar Ian Brownlie underscored ‘the general principle, that pre-independence boundaries of former colonial administrative divisions all subject to the same sovereign remain in being, is in accordance with good policy and has been adopted by governments and tribunals concerned with boundaries in Asia and Africa. Another authority of international law Malcolm reinforced the position by stating that ‘not to accept the territorial solution of statehood emerging from decolonization would require acceptance of another legitimizing principle, such as ethnic or historic affinity’. The claims of the right of peoples to self-determination on the basis of geographical congruity, historical connexion, ethnicity and cultural affinities have been turned down by the international community in the past.

The ICJ in the Advisory Opinion in Western Sahara case, 1975 refused to entertain the claims advanced by Morocco over Western Sahara and the Mauritanian entity. Based on the information placed before it, the Court stated that while there existed among them many ties of a racial, linguistic, religious, cultural and economic nature, the emirates and many of the tribes in the entity were independent in relation to one another, they had no common institutions or organs. The Mauritanian entity therefore did not have the character of a personality or corporate entity distinct from the several emirates or tribes which comprised it. The Court concluded that at the time of colonization by Spain there did not exist between the territory of Western Sahara and the Mauritanian entity any tie of sovereignty or of allegiance of tribes or of simple inclusion in the same legal entity. In the relevant period, the nomadic peoples of the Shinguitti country possessed rights including some rights relating to the lands through which they migrated. These rights constituted legal ties between Western Sahara and the Mauritanian entity. They were ties which knew no frontier between the territories and were vital to the very maintenance of life in the region. The ICJ concluded that there was no tie of territorial sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco or the Mauritanian entity.

With respect to Somalia’s claim over Ethiopia’s Ogaden region, Kenya’s Northeastern Province and France’s territory of Afars and Issas (now called as Somaliland), the issue has been in a state of deadlock due to opposition by international community especially the member States of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). Article 3 of the Charter of the OAU obliges the member States to respect the borders existing on their achievement of national independence. The Somali myth of unity remains unfulfilled. Whether there exists resource dimension to such claims or not, the practice of State and international law does not support such claims over territories protected by international law. Iraq’s claims over Kuwait in 1990s were similarly frustrated by UN Security Council resolutions such as 660 adopted on August 2, 1990, 678 adopted on November 29, 1990, etc.

Claims to integrate or unite geographically contiguous areas into one political administrative unit on the basis of historical connections, ethnic and cultural ties are not sustainable in international law, state practice and jurisprudence established by the international tribunals. Claims over Manipur’s territory or portions of its territory are non-sustainable and against the established norms of international law. If such claims should have been justified then there would be no country left which cannot be integrated with one powerful State. Such a situation would usher into endless chaos, fratricidal struggles and bring instability in regional or international peace and security which would ultimately trigger a permanent doom for the entire humankind. Responsible leaders advocating national aspirations throughout history understand this proposition. Responsible and matured leadership of Manipur’s cause never makes such a proposition that Manipuris settling in Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Assam should be integrated into one larger Manipur.

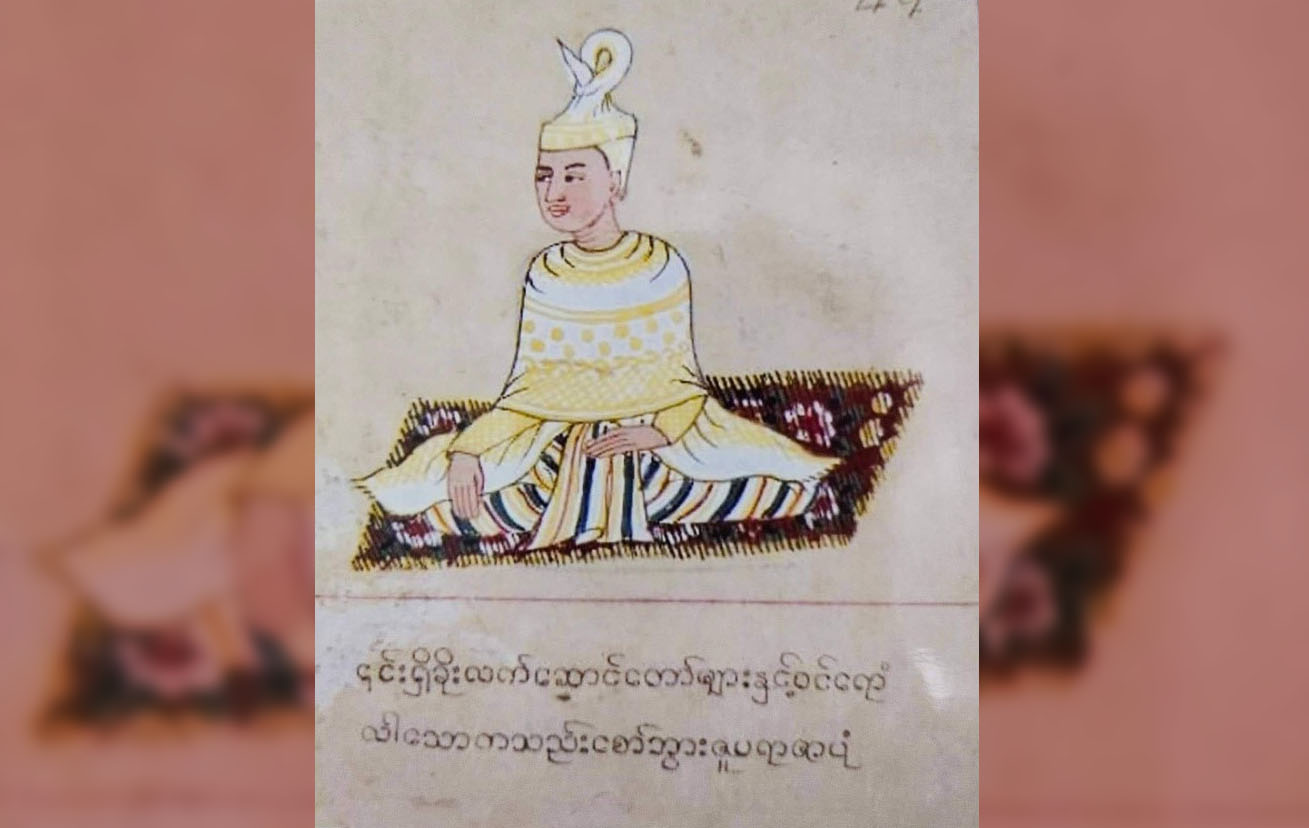

UTI POSSIDETIS JURIS BEYOND TERRITORIALITY

People or nationhood is central to the ideas of territory and sovereignty. The protection of territorial integrity without the well-being of the people inhabiting in the territory is incomplete. And the concept of terra nullius is irrelevant to Manipur’s case. Manipur’s existence as a historical and political power in Asia as recorded from Henry Yule’s map of 1500 A.D., treaties concluded between East India Company and Manipur on the one side and those concluded between British East India Company and Kingdom of Burma (Ava) during 1762 to 1885, grant of Sanad by the Imperial British Government in 1891 and 1918 to the Manipur State Constitution Act, 1947, etc. nullifies the scope of terra nullius in the context of Manipur. Manipur was considered as a formidable power during 18th and 19th centuries as recorded in the accounts of Col. Johnstone in 1874 although with periodic invasions by the Burmese forces. Therefore, the principle of uti possidetis juris beyond the territorial scope becomes necessary to explore the rights of the people inhabiting therein. Protection to boundaries and territories without safeguarding the rights and well-being of the people residing therein seems to frustrate the central idea of ensuring stability of borders which uti possidetis juris seeks to preserve. Non-territorial aspects of the principle thus necessarily involve the rights of the people inhabiting the territory such as their polity, society, culture, etc. Apart from preserving the inviolability of the territory in question, uti possidetis juris seeks to protect any changes in demography, settlement patterns, division or bifurcation of the territory which affects its composite identity, etc. Uti possidetis juris protects both territorial and non-territorial integrity of Manipur. India cannot disturb or alter Manipur’s original state of ethnic composition, settlement patterns and composite character of its demography, society and culture which existed in 1947. The international norm of uti possidetis juris rises to protect Manipur’s historical and political personality and integrity both territorial and non-territorial as it stood on August 15, 1947.

India is also a state party to the Four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and it had enacted the Geneva Conventions Act, 1960 to give effect to the provisions of the Geneva Conventions. Articles 47, 50 and 54 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, 1949 prohibit the GOI to change or alter the historical and political status of Manipur. India’s constitutional relationship with respect to Manipur is circumscribed by the above-mentioned legal provisions of treaties and principles of international law. Article 3 of India’s constitution does not have jurisdiction over Manipur.

References

- White Paper on Indian States, Ministry of State, Government of India, 1950.

- Government of India Act, 1935.

- Constitution of India, 1950.

- Manipur State Constitution Act, 1947.

- Cabinet Mission Plan, 16th May, 1946.

- Memorandum on States’ Treaties and Paramountcy, 12th May, 1946.

- Manipur Administration Order, 15th October, 1949.

- Manipur Merger Agreement, 21st September, 1949.

- Fourth Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War on Land, 1907.

- North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971.

- Four Geneva Conventions, 12 August, 1949.

- Geneva Conventions Act, 1960.

- UN Charter, 1945.

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 2625 (XXV), 1970.

- Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Rep 136, 2004.

- Resolution adopted by Manipur National Assembly on 28th September, 1949.

- National Convention on Manipur Merger Issue on October 28-29, 1993, PDM, 1993.

- Case Concerning the Frontier Dispute, ICJ Reports 1986, Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali.

- Arbitration Commission concerning Yugoslavia and Macedonia, 1991.

- Vienna Convention of 23 August 1978 on the Succession of States in Respect to Treaties, 92 ILR 171.

- 1955 Treaty between Libya and France.

- Temple of Preah Vihear, ICJ Reports, 1962, p. 34.

- Aegean Sea Continental Shelf, ICJ Reports, 1978, p. 36.

- Treaty between Gumbheer Singh and British Commissioner F.J. Grant, 1835.

- Proclamation of H.H. the Maharaja of Manipur, dated 18th October, 1948.

- 1834 Agreement regarding Compensation for the Kubo Valley.

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969.

- Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1966, vol 2.

- Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties 1978.

- Tunisia/Libya case, ICJ Reports, 1982.

- Helsinki Final Act, 1975.

- Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1974, vol. I.

- Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law, 4th edition, 1990, Oxford University Press, p. 135.

- Western Sahara, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports 1975.

- AHG/Res. 16 (I), 1964, Organisation of African Unity.

- David D. Laitin, Somali Territorial Claims in International Perspective, Africa Today, Apr. – Jun., 1976 vol. 23, No. 2, Tensions in the Horn of Africa (Apr. – Jun., 1976), pp. 29-38, 33.

- UN Security Council resolutions 660, August 2, 1990, 678, November 29, 1990.

- Henry Yule’s map of 1500.

- Treaty of Yandaboo, 1826.

- Pemberton Report, 1835.

- Malcolm N Shaw, International Law, 9th Edition, 2021, Cambridge University Press.

- McNair, Law of Treaties, Oxford University Press, 1961.

Assistant Professor, Symbiosis Law School, Pune and can be reached at laishram.mangal@symlaw.ac.in. The views expressed herein are author’s own

1 thought on “The Distinctive Historical and Political Status Of Manipur”

I express my congratulations and best wishes to Dr. Laishram Malem Mangal.

Very well written, the best article I have read in recent times. It is a breather in these turbulent days. It will give a big blow to those trying to break Manipur apart.

Comments are closed.