A chain of events of eighteenth and early nineteenth century in the kingdoms of Manipur, Burma (Myanmar) and British expansionism are minutely analysed in the article to understand the factors which led to seven years devastation (1819-26), in Manipur known as “Chahi Taret Khuntakpa” and in Assam known as “Manor Din” or “Days of Darkness”, and Sir Edward Gait’s book, “A History of Assam”, 1906, its referred to as “Manar Upadrab”, or “oppressions of the Burmese”, and the broke out of First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26) between the British and the Burmese.

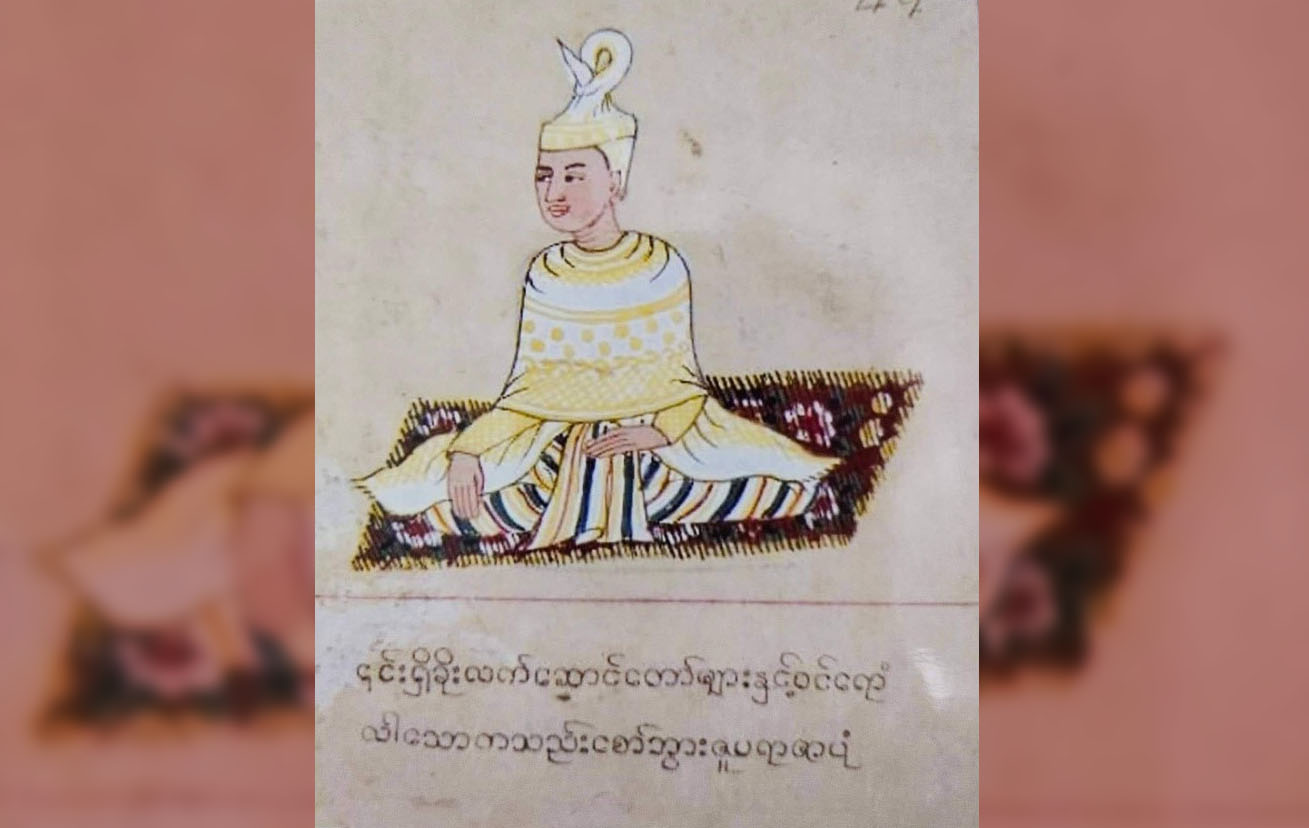

The great sovereign monarch Gariba Niwaza (Pamheiba) r. 1709-48, changed the course of history in kingdoms of Manipur and Burma (Myanmar). In Gariba Niwaza’s reign Manipur was at her zenith and an Asiatic power in Southeast Asia. The Toungoo king Maha dama yaza dipati had sent letters to Chinese Qing emperor and sought help to crush Manipur. The writings of several Western and Burmese scholars mentioned the might of Gariba Niwaza, and his Burmese expeditions that threatened the then Toungoo Empire.

The first half of the eighteenth century Manipur kingdom was a formidable one, and had strategic military alliance with Cachar, and was part of the confederacy with Tai kingdoms of Northwest Myanmar. In 1740, the golden opportunity arose for Manipur, the chance to conquer Ava and established her dominion in mainland Southeast Asia after defeating the Burmese Toungoo Empire. In this regard renowned author Victor B. Leiberman in his book, “Burmese Administrative Cycle: Anarchy and Conquest, C. 1580-1760”, 1984, writes,

“The brahmanically sanctioned changes that Gharib Newaz introduced in political organizations, in personal devotion, in diet and dress inspired the Manipuris with a vast energy and missionary dynamism. Gharib Newaz’s raids against Burma were concentrated in the latter part of his reign after he had inaugurated his reforms, and these raids at once took on a religious justification.

Gharib Newaz bears comparison with rulers of the Koch kingdom and the Ahom kingdom in Assam, and rajas in the western state of Cachar, whose political and military success were intimately linked with the progressive Hinduization in northeast India, which happened to reach Burma’s frontiers at a particularly inopportune time from Ava’s standpoint.

Gharib Newaz, who by 1740 had consolidated control over a zone of northern Shan tributaries formerly loyal to Ava, now concluded that a full-scale conquest was within his grasp. At the end of the rains he advanced with the combined Manipuri-Cacharese army said by the Burmese to have been twice as large as their principal defense force. Yet the invasion miscarried. Burmese attributed its failure to their improved defense. Probably of equal importance was the fact that Gharib Newaz’ enemy the ruler of Tripura exploited Gharib Newaz’ absence to menace the valley of Manipur from the west. Gharib Newaz hastily withdrew, therefore, to secure his position in his home area. According to Burmese sources, reports of the Manipuri raid on Sagaing precipitated the 1740 revolt at Pegu.

Thus Ava’s Tai vassals in the northwest found it profitable temporarily to become vassals of Manipur, but in the northeast, southeast, and east, the pull of nearby empires was insufficient and breakaway principalities preferred independence. Furthermore, as Ava’s coercive power declined, the first areas to leave the imperial orbit were naturally at the most distant reaches of the empire (hill tracts near Mong Pai, Manipur, and Chiengmai) followed at a relatively late stage by principalities in the Irrawaddy basin.”

Gariba Niwaza’s religious preceptor Shanti Das was well regarded and known to the Burmese by the name of Mahatharahpu. The mission of Shanti Das was to convert Burma into a Hindu kingdom.

In this regard the renowned scholar Michael W. Charney writes on Shanti Das’ Hinduizing mission plan for the Burmese kingdom as follows:

“The rapid transformation of Manipuri society was intended to be extended over Burma in the same way. The guru Shanti Das, behind all of this left the Manipuri court for the Burmese royal court in August 1733. According to the Manipuri sources, Shanti Das returned to Manipur in November/ December 1733, because he had been denied entry into the Burmese royal court. Gharib Newaz accompanied by Shanti Das gathered an army and, headed by the flag of Hanuman, took it against the royal capital of Burma, only to find his passage blocked by the Irrawaddy River, which the Manipuri cavalry were unable to cross. Shanti Das is also said to have encouraged the Manipuri attack by instructing the Manipuris that by drinking and washing themselves with water from the Irrawaddy River, they would completely cleanse themselves of misfortune and danger. The guru set out again in 1743 officially to negotiate the provision of a Manipuri princess to the Toungoo king. However, the Manipuri court chronicle implies, he had set out to conquer Ava again. Further, according to Lower Chindwin authors writing in the late 1820s, Shanti Das wanted to establish Hinduism (‘our way of thinking’) in the mind of ‘the king who lives in Ava’. There is, thus, little doubt that Shanti Das had major plans for the Burmese court, especially since his large entourage consisted of five hundred of his disciples, including Brahmin priests.

The reshaping of Manipuri culture and religion under Gariba Niwaza was pervasive. This rapid transformation of Manipuri society was intended to be extended over Burmain the same way. If there had been any real chance of a conversion of Burma to Hinduism this was doused by the end of the 1750s. After the Burmese royal capital fell to the Mons in 1751, we hear little about the Lower Chindwin or Manipuri–Burmese interaction until the Burmese kingdom under King Alaungpaya was fully restored in 1756.”

The book titled, “The Situation in Myanmar 1714-52”, written by Burmese scholar Dr. Yi Yi, Senior Researcher, Department of History, Ministry of Culture, Myanmar; has a chapter on Burma–Manipur War during monarchy period. Dr. Yi Yi records the visit of religious preceptor Shanti Das with Gariba Niwaza’s son Samjai Khurai-Latpa at the royal court of Ava in 1743.

Shanti Das died in 1744 at Sagaing Thante due to Cholera. The body of Shanti Das was dumped in Irrawaddy River in quick succession after performing Jal Samadhi (Hindu ritual of water burial). Afterwards Samjai Khurai-Latpa and five hundred disciples of Shanti Das returned to Manipur.

According to R.K. Jhalajit Singh, Shantidas, the religious guru of the king died on Tuesday 27 Hiyangei (September/ October) 1744 in Burma.

The mission of Shanti Das to convert Burma into a Hindu kingdom remained unaccomplished due to his untimely death in 1744. However, the Toungoo Empire remained threatened in Gariba Niwaza’s reign and finally, the Toungoo rule was ousted by the Mons.

The founder of Konbaung Dynasty Alaungpaya (r.1752-60) hailed from Shwebo, which lies on the eastern bank of Chindwin River (Ningthee Turel) and saw everything with his own eyes, the downfall of Toungoo Empire, and he took Manipur and Mon as his arch rivals. Alaungpaya ascended the Burmese throne after defeating the Mons. Alaungpaya invaded Manipur with a large expeditionary force which was well equipped with modern arms acquired from the French and the Portuguese. The Khooltak Ahanba or primary devastation of Manipur happened in his reign.

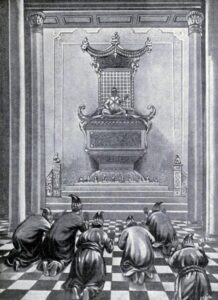

Royal Order of Burma (ROB) 19 January 1759; Alaungmintaya, the Most Excellent King, Defender of the Buddha’s Religion, Possessor of Arindama Lance, Master of White, Red and Spotted Elephants, Lord of the Golden Palace, Leige of Various Kingdoms in Jambudipa, proclaimed that all land known as Manipur is annexed to his empire from this day of 12 January 1759 and to make it a lasting record for all generations to come, this proclamation is inscribed on stone. Any ruler over this land of Manipur shall send either his sister or his daughter as a bride to his liege lord in Burma once in every three years. They were also obliged to annually offer tribute of a great amount of gold, as well as horses, bows, arrows with poisoned iron tips and tree gum to the Konbaung court including a force of 2,000 men to join the imperial army whenever war broke out.

Alaungmintaya started the Manipur campaign on 12 November 1758. He took the town of Manipur on 2 January 1759 and left in on 22 January 1759. This record was inscribed on stone by Thet Shay Nawyatha and the inscription stone was erected in Imphal right in front of the Langthabal palace.

As for Alaungpaya, in attacking Manipur he explained that he sought to crush the religious errors of the Hindus. Although Arakanese, Shans, and Siamese were also Theravadin, on invading their realms, Burman leaders explained that they had come to reform “corrupt” practice so that the Lord Buddha’s Religion might shine once again.

G.E. Harvey writes on Alaungpaya’s conquest of Manipur as follows:

“Alaungpaya in his invasion of Manipur in 1758-59 when the Manipur durbar had relapsed into a series of sanguinary plots after the death of Gharib Newaz, and one of the claimants took refuge with Alaungpaya, to whom he presented some princesses. Alaungpaya now proceeded up the Chindwin, devastating the villages of the Kathe (Manipur) Shans on the west bank: he crossed the hills by the Khumbat route, and entered the Manipur Valley. The Manipuris say he was unspeakably cruel; but he was only doing unto them as they had done unto his people. In his capacity as a divine incarnation he promoted religion among the Kathe Shans on his line of march; in his capacity as a king he massacred more than four thousand of his Manipuri prisoners because they stubbornly refused to march away into captivity.

These incursions, lasting down to 1819, ended by depopulating the country and stamping out Manipuri civilization so completely that we can no longer tell what civilization was like.

Alaungpaya deported thousands of Manipuri boatmen, silversmiths and silk-weavers to the royal capital area. These people, with later contingents of Manipuri deportees, came to form a significant segment of the population of the Burmese royal city as it moved from one site to another. There, they formed substantial colonies of artisans, cultivators, cavalry, and other types of royal servicemen, and Manipuris formed whole villages and continued to communicate in Manipuri as well as in Burmese.

- Roy in context to invasions of Manipur by the successive Konbaung kings starting from Alaungpaya to Bagyidaw writes:

“From 1758 A.D. to 1826 A.D. -within this period of 68 years, Manipur was overrun and dominated by the Burmese, times without number. They must have tried to force their religion upon the people they conquered. An image of Buddha found in Manipur was probably imported during that period. Inspite of it, Manipur did not accept Buddhism.”

Manipur king Bhagyachandra (r. 1759-62, 1763-98) was fully aware of the changing international situation in the region specially the conflict between the French and the British in India and Burma during the Seven Years War (1756-63). The English became masters of Bengal after the momentous Battle of Plassey in 1757. The Bengal of those days was comprised of modern West Bengal, modern Bangladesh, Bihar and Orissa

The British expansionist plans is mentioned in the writings of Dr. PN Chopra in his book, “The Gazetteer of India: History and Culture Volume Two”, 1973, as follows:

“The 18th century was an important landmark in the respective histories of Burma, Manipur and Assam. The glory of the three countries was equally in zenith. However, by the turn of the 19th century the British had appeared restless for implementing their policies to make establishment of their rule over the western and eastern frontiers of India. As a matter of their consolidation policies, control over the western frontier was secured by annexing Sind and Punjab and by making Afghanistan a buffer state between the British and the Russian empire. Control over the eastern frontier was to be secured by annexing Lower Burma and by establishing British authority over Assam, Manipur, Cachar and Jaintia. In addition, the process of political unification of the country was to be hastened by annexing some of the problem states. On the eastern frontier, war between Burma and British India played in the logic of history, for it was of vital importance to both the countries to secure control over the frontier by annexing Assam, Manipur and other border states. Slowly but almost inevitably events moved to a crisis and led to First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26).”

The relations between Britain and Burma were suspended when Alaungpaya in October 1759 massacred British merchants at Cape Negrais who were suspected of aiding a local revolt. The action of Alaungpaya made Britain look for new allies. On the other hand, Manipur was facing existential threat from the Burmese invasions.

In this context, it is also worthwhile to study the mind and intention of the British when the First Anglo-Manipuri Treaty of 1762 was drawn. According to G.E. Harvey in his book, “History of Burma from the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824: The beginning of the English Conquest, 1925”, put the following versions; in 1762, angry at the Negrais massacre, the English had made a treaty with the Manipuris against the Burmese but had done nothing in fulfilment; even now they refused both applications, saying they could not interfere in internal affairs.

According to Professor Gangmumei Kamei the Anglo-Manipur treaty was concluded on 14th September 1762 between Vakil Haridas Goswami on behalf of Jai Singh, the Raja of Meckley (Manipur) and Henry Verelst the Chief of Chittagong Factory and acting Governor of Bengal. The Treaty was approved by the Bengal Government, of which Mr. Vanisitart was the Governor of Bengal, on 4th October 1762. Ananta Shai (Ananda Shah, Podullo Singh and Chitton Singh) were involved in the negotiations.

According to J. Roy the terms of the Treaty the alliance between the Government of Manipur and the British Government of India was finally and firmly settled.

Horace Hayman Wilson in his book, “The History of British India: From 1805 to 1885”, writes on Anglo-Manipur Treaty as follows:

“In 1762, a treaty of alliance offensive and defensive was concluded between the Raja of Manipur and Mr. Verelst, then Governor of Bengal, in virtue of which a small detachment marched from Chittagong, with the declared design not only of enabling the Raja to expel the Burmas from his principality, but of subduing the whole of the Burma country.”

After the conclusion of Anglo-Manipur treaty of 1762, the threat of invasions by the Burmese continued over Manipur.

Royal Order of Burma; Early in the Kun: Bhon period Manipura was a prize conquest. It sent a tribute every year and a bride for the king once in every three years. It had sent a force of 2,000 strong in time of war (ROB 19 Jan 1759). This arrangement did not last long. Five years later Manipura did not send the yearly tribute in the reign of Hsinbyushin. When it was demanded (2 July 1764) Manipura just ignored it. That prompted the Mranma to launch yet another invasion of Manipura. The result was that many of its peoples were brought back to Mranma and given as servants to princesses, etc.

According to Sithu Thant in his write up, “Who are the Manipuri Kathes”, 2020, stated,

“In 1764 AD, during the reign of King Hsinbyushin, the Burmese launched another expedition to Manipur. The reason behind the expedition was to remove Jai Singh (Bhagyachandra) who dethroned the Burmese puppet ruler. The Burmese won in that war and they brought the Manipuri war prisoners including the former King Jai Singh to Myanmar.”

Bhagyachandra succeeded in coming to an understanding with the Konbaung emperor Bodawpaya (r.1782-1819) after his ascension to the Burmese throne and was allowed to remain in quiet possession of his devastated country.

According to Gangmumei Kamei after the death of Bhagyachandra, in November 1801 one Daoji and Gambhir Singh hatched a conspiracy and one day in the same month the king Labanyachandra was assassinated by Angom Chandramani, perhaps a henchman of Gambhir Singh. This was a bad omen for the ruling dynasty of Manipur. The same thing of conspiracy was followed by the exceedingly ambitious young prince Marjit against the kind hearted king Chaurajit. Having failed in the conspiracy Marjit escaped and fled to Burma to get help from Emperor Bodawpaya to dislodge his brother Chaurajit from the throne of Manipur. King Chaurajit and Prince Gambhir Singh fled to Cachar to take refuge there. Marjit was installed as the king of Manipur in 1813 by the Burmese by accepting their suzerainty.

Lt. General Sir Arthur Phayre in his book, “History of Burma”, 1883, records “In 1806 prince Marjit Singh sent presents to Bodawpaya, soliciting his support. King Chaurajit also sent presents, and one of his daughters, in token of fealty. Bodawpaya summoned the Raja to his presence in order to settle the dispute”.

The Konbaung emperor Bodawpaya had 206 wives out of which 16 were Manipuris.

Jacques. P. Leider in context to dispute between Marjit and Chaurajit wrote, “As for Emperor Bodawpaya, he knew that dynastic conflicts at Manipur’s court after 1799 favoured Burmese meddling and a number of Emperor Bodawpaya’s orders illustrate this interference in the years 1806 and 1807.”

Lt. General Sir Arthur Phayre further wrote, “Chaurajit refused to come; a Burmese army marched into Manipur; the raja was defeated, and fled into Kachar; Marjit was placed on the throne, and the Burmese army was withdrawn. From this time the Kubo valley was annexed to Burma in 1813.”

In a very short time after the installation of Marjit Singh on the throne in 1813, Bodawpaya wasted no time and annexed Manipur the following year in 1814 and the relations soured between Manipur and Burma.

Just after Bodawpaya became king of Burma in 1782, he had already acquired western kingdom of Arakan in 1784 and afterwards he annexed Manipur on 15 February 1814 and Assam in 1817, leading to a long ill-defined border with British India. Regarding the invasion of Manipur for annexation by the Burmese in 1814, Maha Bandula (Maung Yit) first battlefield experience came in Manipur. On 15 February, 1814 a 20,000 strong Burmese army left their forward bases along the Chindwin to invade Manipur in order to place their nominee on the Manipuri throne. Maha Bandula served under the command of co-commander-in-chief, Ne Myo Yazathu and had commanded three regiments (3000 men). The Burmese forces easily overran Manipuri defense; Maha Bandula’s regiment participated in the capture of the Manipuri capital.

The British and the Burmese expansionism plans in the early nineteenth century were clearly visible to the rulers of both Manipur and Assam. Manipur after Anglo-Manipur Treaty of 1762 and Bodawpaya’s invasion in 1814 and Assam in 1817, in quick succession both came under Burmese rule. The strained relations between Manipur and Burma reached its climax when Marjit allowed free movements of British soldiers in the territory of Manipur and it’s found in the content of Royal Order of Burma (ROB) dated 8 March 1818, which recorded “In the reign of King Bodawpaya, a letter was sent to Maharaja Marjit Singh to drive out the English from Manipur.”

The diktat of the Burmese emperor Bodawpaya on Marjit proved to be the turning point in strained Manipuri-Burmese relations, and as one of the main factors which eventually led to seven years devastation.

The geography of Manipur is located strategically desired by both the British and the Burmese and served as a springboard to launch attack on one another. This has been evidently proven in the history of Manipur on the account of seven years devastation.

Bodawpaya was offended at the action of Marjit asserting himself as an independent ruler free from vassalage under the Burmese, died on June 5, 1819 and was succeeded by his grandson Bagyidaw (r. 1819-37). The Burmese empire was at zenith in Bodawpaya’s reign. King Bagyidaw inherited the second largest Burmese empire but also one that shared a long vaguely defined borders with British India. The British, disturbed by the Burmese control of Manipur and Assam which threatened their own influence on the eastern borders of British India, supported rebellions in the region.

The new king Bagyidaw summoned Marjit to be present at his coronation ceremony at Ava and pay homage to him which was customary for any vassal ruler in Burma. Marjit perhaps defied the royal summon and refused to attend the ceremony.

In October 1819, Bagyidaw sent an expeditionary force of 25,000 soldiers and 3000 cavalry led by his favourite General Maha Bandula to reclaim Manipur. Bandula reconquered Manipur but the raja escaped to neighboring Cachar, which was ruled by his brother Chourjit Singh. The Marjit Singh and Chourjit Singh continued to raid Manipur using their bases from Cachar and Jaintia, which had been declared as British protectorates.

In the years leading to the war, the king Bagyidaw had been forced to suppress British supported rebellions in his grandfathers’ western acquisitions (Arakan, Manipur and Assam), but unable to stem cross border raids from British territories and protectorates. His ill-advised decision to allow the Burmese army to pursue the rebels along the vaguely defined borders led to the First Anglo-Burmese War. Lord Amherst, the then Governor-General of India, finally on the 24th February, 1824, declared formal war against Burma.

In regard to Burmese invasion of Assam, the insightful article written by Himangshu Ranjan Bhuyan titled, “The Burmese Invasion and Assam’s Struggle for Freedom”, dated 23 March 2023, published by Sentinel Digital Desk, and some excerpts of the article is reproduced below as follows:

The early 19th century was a difficult time for Assam. The Ahom kingdom, which had ruled the region for nearly six hundred years, was weakening. Internal conflicts and power struggles made the administration unstable. This weakness attracted foreign powers, and among them were the Burmese. The Burmese invasions of Assam took place between 1817 and 1826. These invasions caused great destruction and suffering. The people of Assam had to fight hard to protect their land, but they could not resist the powerful Burmese forces. The years of Burmese rule were filled with terror, and the people lived in constant fear. However, their struggle did not end in defeat. Assam’s resistance continued, and finally, with the help of the British, the Burmese were expelled. This period changed the history of Assam forever and had long-lasting effects on its society and governance.

The Burmese invasion did not happen suddenly. Several factors led to this event. One of the main reasons was the internal conflict within the Ahom kingdom. The nobles were divided, and there were frequent fights for power. The kingdom lacked strong leadership, and corruption weakened its military strength. This made it easy for outside forces to interfere. Badan Chandra Borphukan, a powerful noble, wanted to gain control over the kingdom. To achieve this, he sought the help of the Burmese. The Burmese king, Bodawpaya, saw this as an opportunity to expand his empire. He sent his army to Assam in 1817. This marked the beginning of Burmese involvement in the region.

The first Burmese invasion of Assam in 1817 was a major turning point. The Burmese army entered Assam with well-trained soldiers. The Ahom forces, already weak due to internal conflicts, could not resist them. The battle at Ghiladhari was one of the key battles of this invasion. Although the Assamese fought bravely, they were defeated. The Burmese then took control of the Ahom capital, Jorhat. They placed Chandrakanta Singha on the throne but kept him under their influence. The Burmese stayed in Assam, interfering in its administration and weakening the Ahom rulers further.

In 1819, the Burmese launched a second invasion. This time, they were even more ruthless. They removed Chandrakanta Singha when he tried to resist their control. Instead of keeping an Ahom ruler, they placed their own governor in charge of Assam. This marked the beginning of direct Burmese rule in the region. The period that followed was one of the darkest in Assam’s history. The people of Assam suffered greatly under Burmese rule. The invaders looted villages, killed innocent people, and enslaved many. Thousands of people fled their homes and took shelter in the hills and forests to escape the cruelty of the Burmese. This time of suffering is still remembered as the “Manor Din” or “Days of Darkness”.

In the words of Gangmumei Kamei the Burmese invasion of Manipur was a part of a greater plan of conquest of North East India and even Bengal. The Burmese conquest of Manipur in 1819 was different in intention and character from their earlier invasions. This time, they meant to rule Manipur through their puppet rulers. Thus Manipur was brought under the Burmese rule for seven years (1819-26) which is known as the seven years devastation in the history of Manipur. The flight of Marjit from Manipur and Burmese conquest in 1819 marks the end of the medieval period in the history of Manipur.”

The writer is an independent researcher and author of “Vedic Imprint in Southeast Asia: With Special Reference to Manipur” and joint author of “The Political Monument: Footfalls of Manipuri History”. He is an MBA from Sydney, Australia and worked in Myanmar from (2013-16) in hydro and renewable energy space.