Four years after the February 1, 2021 military coup led by General Min Aung Hliang, Myanmar’s destiny continues to remain uncertain. The multiple ethnic fault-lines the country has always had to live with since its independence from British colonial yoke on January 4, 1948, are now coming out of dormancy to make this excruciating civil turmoil even messier.

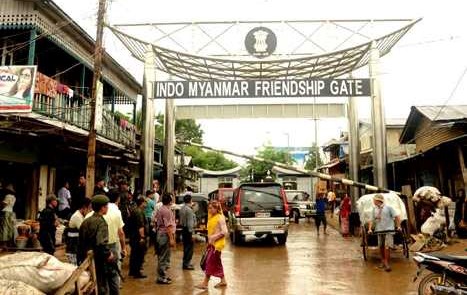

For Northeast states bordering Myanmar, this is very relevant for Myanmar’s problems have always had the tendency to spill over to them. This happened during a similar faceoff between civil resistance groups and the military in the wake of the August 1988 uprising and this is happening again in the current mayhem.

Contrary to what most casual onlookers surmise, the unfolding civil conflict in Myanmar is not so straightforward and is instead multilayered. On the broad canvas, there is indeed the valiant fight put up against the junta by civil militias formed essentially among Myanmar’s majority community Bamar, in different regions of the country.

All these local militias are loosely bound under the nomenclature Peoples’ Defence Force, PDF, but are far from being under a strict and united command structure. The PDF owes allegiance to the coup-ousted National League for Democracy, NLD, of Aung San Suu Kyi, which has now formed an underground government, the National Unity Government, NUG.

The PDF are spontaneously raised militias in response to the coup therefore initially suffered from lack of combat training and firepower, but this shortfall was made by alliances forged with several of Myanmar’s experienced and well-armed ethnic insurgencies which have been fighting the Myanmar Union since its independence.

This equation however is not linear. All ethnic rebel armies, some very powerful, have not chosen to ally with the PDF. Many have remained neutral and some, including civil militias amongst the Bamars, are even fighting alongside the junta and they are locally referred to as “Pyusawthi”. The International Crisis Group, a reputed peacebuilding organisation, in an article called this phenomenon ‘resisting the resistance’.

The complexity of the relationship between the Buddhist Bamar who form 68 percent of Myanmar’s population and other ethnic communities, also becomes apparent even from a cursory look at some social media chat groups of Myanmar people. A contest over a local term “Myo Chit” is a pointer.

This phrase combines the idea of patriotism, nationalism, national fighter, and pride in peoplehood. The junta is wont to using this term to describe itself and its soldiers, and this is ridiculed by an overwhelming majority in these forums.

Interestingly, when the PDF uses it to describe itself, there is unease that this may alienate the non-Bamar ethnic allies, for this signifies the Bamar-defined hegemonic idea of Myanmar nationalism which the latter revile and have been fighting to severe themselves from. Quite obviously, even if the junta is defeated – which many close and neutral Myanmar observers such as Bertil Lintner and Richard Horsey think is unlikely – Myanmar’s endemic existential crisis brought by powerful ethnic unrests is unlikely to be resolved.

It is relevant that even during the NLD rule after the 2015 election, the Myanmar union’s distrust of the ethnic states was not purged. In this election, Shan State and Rakhine State, returned local parties as majorities, yet the Union government under Suu Kyi’s party used a draconian clause in Myanmar’s 2008 constitution to impose NLD chief ministers in these two states to ensure control of their administration. Obviously, this perceived threat to Myanmar’s integrity supposedly posed excessive autonomy to the outlying ethnic states is not junta specific.

The Myanmar military, or Tatmadaw, obviously overestimated its own influence and underrated the resistance capability of the Myanmar people when it decided to grab power four years ago. The junta’s plan, though with no specified timeline, seems to be to hold election to reinstall a popular government as an honourable exit strategy for itself.

But for this strategy to be trusted by the rest of the country, the Tatmadaw will also have to be satisfied with just its role as the country’s military, shedding its other self-assumed role as the country’s guardian. So far, it has been intoxicated by the idea of dwifungsi which Bertil Lintner wrote is borrowed from the Indonesian military’s outlook.

This article was first published in The Telegraph. The original can be read HERE