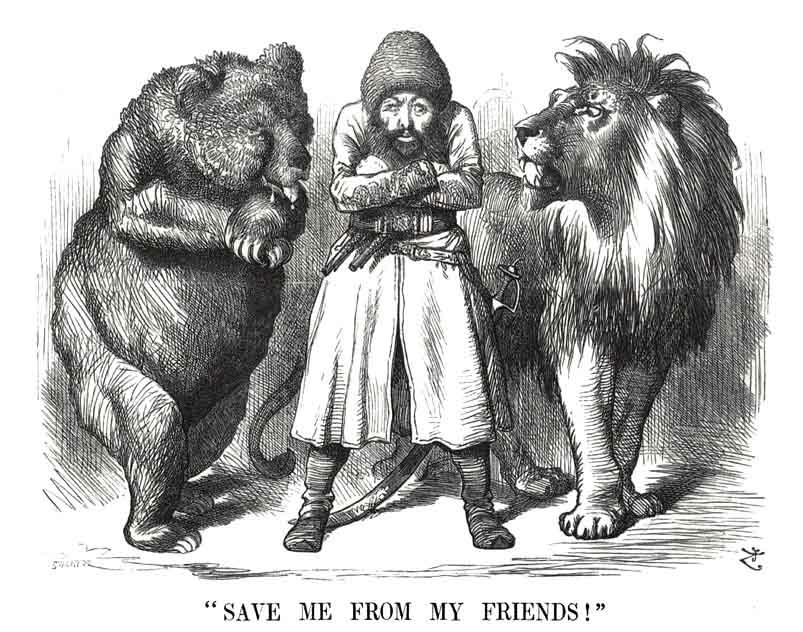

Often, rarely visited pages of history provide refreshing insights into present problems. This is not surprising, considering many of the postcolonial world’s problems are legacies of a past era marked by rivalries of silent ploys and counter-ploys between colonising European powers, carefully harnessed so they did not escalate into open conflicts.

Northeast India is among the regions still facing the consequences of one such rivalry between Imperial Britain and Tsarist Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – the Great Game. The dispute over the McMahon Line, the periodic border skirmishes most notably the flashpoint at Doklam in the Sikkim sector in June 2017, are only some evidences.

The Doklam case in which India strongly objected and prevented China from building a road in the Doklam plateau in Bhutanese territory but close to the Indian border is especially illustrative. It will be recalled the Chinese claimed the part of Doklam they were building the road belonged to them citing a boundary treaty they signed with the British in 1890, determining Sikkim’s territorial extent. The British also signed another treaty with the Chinese in 1893, to allow setting up of a British India trade mart at Yatung in the Chumbi valley contiguous to Doklam.

The history of these treaties is intriguing for the fact that they were signed with China not Tibet. Were the British recognizing the suzerainty of China over Tibet? This is not quite so. The answer has more to do with the Great Game, as China-born British scholar Alastair Lamb, author of the monumental two volume work: The McMahon Line, A Study in Relation Between India, China and Tibet 1904-1914 says in his portrayal of the Lingtu blockade by Tibet.

For at least a decade at the time, the British had been contemplating a permanent presence in Tibet and towards this end in 1886, they had planned a trade mission to Lhasa under the command of an adventurous civil servant, Colman Macaulay. This was to be done on the strength of an unequal Chefoo Convention, 1876, forced on the Chinese in Peking. Among others, the convention made British subjects have rights within Chinese territory. The Chinese, still too weak to oppose the British, weakly conveyed their reluctance to permit the Coleman mission saying the Tibetans would oppose the plan, indicating they were unsure of their control over Tibet.

The Macaulay mission was ultimately suspended for several reasons, but Alastair Lamb suspects it had little to do with British wanting not to embarrass the Chinese at their inability to control the Tibetans. Instead he thinks it was after tacitly coercing the Chinese to recognize the British annexation of Burma in 1885, a country Manchu rulers considered as their tributary.

Not knowing the mission had been called off, the Tibetans sent a detachment to the Sikkimese village of Lingtu, over which they reasserted their ancient claim. Then “on the main road from Darjeeling to the Tibetan border at the Chumbi Valley, along which Colman Macaulay was expected to travel, the Tibetans set up a military post; and they refused to retreat even after there ceased to be any question of a British mission,” Lamb writes.

Despite appeals by the British to the Chinese to have the blockade lifted, the Chinese could do nothing. At this, Viceroy Dufferin in 1888 authorised the clearing of the blockade by British forces. Dufferin also became convinced Tibet affairs is best dealt with Lhasa not Peking. However, earlier policy outlook was not abandoned immediately, and the 1890 boundary treaty and the 1893 trade treaty were signed with Peking not Lhasa.

Lamb points out the reason is Britain’s anxiety that entering into international treaties with Tibet, would give the Tibetans de jure sovereignty status in the eye of international law and this may encourage the Tibetans to enter into independent treaties with other European rivals, in particular Tsarist Russia. To the British at the time, China was the lesser danger.

The Great Game anxiety made Britain again push for the St. Petersburg Convention 1907 with Russia, already on the backfoot after a naval defeat at the hands of Japan in 1905. To ensure Russia is kept at a distance from Tibet, the treaty made it mandatory for both Britain and Russia to deal with Tibet only through China’s mediation. This complicated matters for the British when the Simla Conference of 1913-1914 was held to define the India-Tibet (China) boundary, and China had to be made a party to the conference. China walked out midway and the boundary agreement was with Tibet alone, prompting China not to recognize it.

Earlier, Curzon adopted the Dufferin outlook. When he became convinced that the 13th Dalai Lama was leaning towards Russia, he authorized the Younghusband Mission in 1904, to invade Tibet. Though the Dalai Lama escaped to Mongolia, Younghusband forced the Lhasa Convention 1904 on the Tibetan government. Among the many humiliating concessions, the Tibetans were to pay a war indemnity of Rs. 75 lakhs, an amount beyond Tibet capacity to pay, and until this amount was paid, Chumbi valley was to remain with India.

In the years after Curzon, liberals like Morley, secretary of state for India in London, made sure the Lhasa Convention was virtually undone and replaced by the Peking Convention 1906, this time signed not with Lhasa but Peking. Another dichotomy of vision between the British home government and the colonial government also became evident. If men like Curzon believed controlling Tibet was important for India’s security, Morley and others were fearful rivals may want to emulate Britain’s outlook in Tibet in other sensitive regions like Mongolia, Afghanistan and Iran.

If not for Britain’s Great Game anxiety, the counterfactual possibility is, monastic states like Tibet, and so too Sikkim, could have remained as Bhutan has. Such a scenario probably would have meant a very different security environment in the entire Northeast region.

The British Empire has dissolved, but not the problems created by its anxieties. Chumbi Valley, wedged between Sikkim and Bhutan, today remains like a dagger pointed at India’s Siliguri corridor which connects the Northeast with the rest of India. But in today’s drastically altered context, perhaps the only way to change for the better is for India and China to find ways to become friends again.

This article was first published in The New Indian Express under a different headline. The original can be read HERE