Following the invasion and occupation of Assam and Manipur by the Seventh ruler of the Konbaung dynasty, King Bagyidaw of Burma in the early 19th Century, the British felt their province of Bengal was made vulnerable and intervened. They annexed Assam and merged it with Bengal after defeating the Burmese in the First Anglo Burmese War and the signing of the Treaty of Yandaboo in 1826. The British also helped two Manipur princes and their army in exile in Cachar liberate Manipur but the latter was left as a protectorate state.

Good as the British were in sizing up their adversaries, after this war the they were confident Burma was in no position to pose any threat for them thereafter. They did however fight two more wars with Burma in 1852 and 1885, but as South East Asia scholar, Alastair Lamb puts it in Asian Frontiers: Studies in a Continuing Problem, these were no more than excuses to annex territories and that the British “swallowed Burma in three gulps”.

This being their security assessment, not long after this war the British withdrew their regular troops, and in their place raised civil militias, Cachar Levy and Jorhat Militia in 1835. The latter merged with the former the same year and thereafter came to be known by different names, including Assam Military Police. How this militia, “less paid than the military but better armed than the police”, grew in stature and importance to be finally upgraded to be India’s first paramilitary force, Assam Rifles, in recognition of their contribution to the British war effort during WWI is well documented by colonial military historian, L.W. Shakespear.

Meanwhile, another security concern grew – that of raids by hill tribes on the more plentiful plains during lean seasons. The Ahom had dealt with this by a practice known as posa whereby the hill tribes were given a share of the plain’s produces in kind each year on the promise they would not raid to deserve retributive counter raids. The British borrowed this and also introduced the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation of 1873, by which an “Inner Line” was drawn to separate the revenue plains of Assam from the “wild” hills which were to be left least interfered and unadministered. The hills beyond the “Inner Line” came to be later designated as “excluded areas” and “partially excluded” areas.

Ironically, this line which was drawn originally to secure the revenue plains from raids from the hills is now seen as a protection provided for vulnerable small hill populationss by the British, and indeed with a measure of truth in the changed social circumstance of postcolonial India.

There were other complications resulting from the Inner Line. One of these was that although the name itself implied an Outer Line as well, this was never drawn. The story of the McMahon Line – which is part of this implied Outer Line – drawn in a hurry during the 1913-1914 Simla Conference when the Inner Line came to be too often and dangerously mistaken for the international boundary, is illustrative of this.

The legacy of this colonial frontier management lives on in the Northeast, but nowhere has it taken a more mutant form than in Manipur. After the First Anglo-Burmese war Manipur was left as a protectorate state considering its strategic location. Indeed, Lord Curzon, who explains his notion of the three-layered buffer of British colonial frontiers in his Romanes Lecture 1907, also had visited Manipur in 1901.

From 1826 to 1891 Manipur remained a close ally of the British, participating in several expeditions of the British in controlling their eastern frontier, including an expedition to Kendat in Burma during the Third Anglo-Burmese war in 1885, to rescue European employees of the Bombay Burma Company based there.

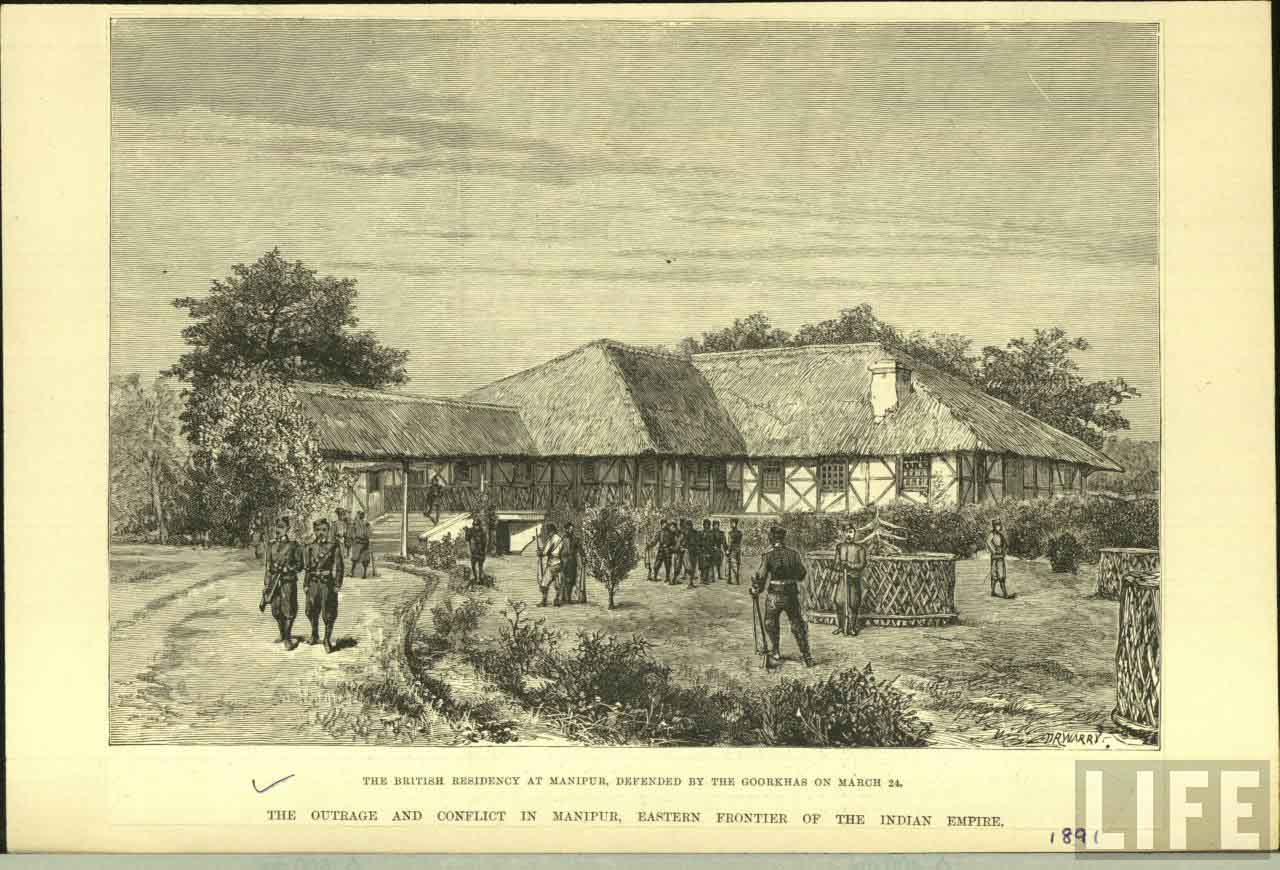

In 1891 however, when a palace revolt over the crown broke out between siblings princes, the British made an unwarranted intervention leading an open war in which Manipur was defeated. The British deposed the rebellious king Kulachandra and banished him and also either executed or banished his blood brothers. Because the British did not immediately think of a successor to the throne, by the Doctrine of Lapse introduced by Lord Dalhousie in 1859, Manipur came to be automatically annexed by the British and this lasted from April 27 to September 22, 1891.

But after finally agreeing on an idea of putting a scion from a different royal blood line on the throne, they reverted Manipur back to the status of a protectorate state. Their choice, Churachand was however only 5-year-old and so till he came of age and while he was being educated at Mayo College in Ajmer, the then British political agent acted as the regent.

In 1907, Churachand was coronated but it was the British who determined the broad architecture of the princely state’s administrative structure. A Manipur State Darbar was formed, and the President of this Darbar was the British Political Agent, taking somewhat the role of the Governor in British ruled province of Assam. The tried and tested administrative mechanism from Assam of separating the hills and plains was also introduced, whereby only the plains were to be the administered and the hills left as unadministered “excluded areas” though without actually drawing an Inner Line as in Assam. They also left a corridor between the hills and plains as “Sadar Hills”, which was to be neither hill nor valley, somewhat the equivalent of “partially excluded” area.

Independent India has allowed a mutant version of this system to remain in Manipur, therefore in matters of land revenue administration, the state follows two laws, one for the hills and the other for the Imphal valley, causing escalating complications and dangerous frictions between its ethnic communities. Imphal valley follows modern land revenue law and its benefits are open to all domiciles, but the law for the hills is exclusionary, especially to the valley dwellers –Meiteis.

Even Sadar Hills, now Kangpokpi district, which was originally meant to be neither hill nor valley, is now considered a hill district, though there are still elements of hybridity of the two land laws followed here. For instance, Nepalis can own land, vote and even contest elections here, but not the Meiteis. Consequently, a hostile mental distancing is now crystallising. In Manipur’s ethnic cauldron, this can lead to tragic outcomes.

It is time for change. Manipur needs to come under one modern land revenue administration, though with reasonable variations introduced for different topographies, cultures, economic practices of communities etc.

This article was first published in The New Indian Express and the original can be read here