From the volume Confluence: Essays on Manipuri Literature and Culture complied and edited by B.S. Rajkumar.

Nabadwipchandra could not remain confined to a few trades. As a Mathematics teacher he was very eager to learn astrology. So, he started studying related books earnestly. Not satisfied with this alone, he got guidance in this subject from a renowned astrologer of his time, Khomdram Sanajaoba who was himself the Read Master of Pettigrew School. But he did not become a professional panji, astrologer. Yet he introduced a calendar called Thabal Thachat. He was also able to predict future after deep meditation having offered tulsi to his lord “Giriraj” to whom he was deeply devoted. He did not do it frequently. He was a god-fearing religious person who believed heart and soul in the Goudiya Vaishnava Dharma. He was a staunch follower of the teachings of Shri Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. He always used the Kathari which is an indispensable item among monks. He always wore a saffron vest. He studied zealously many writings on Vaishnava dharma. Many of his poems, for example Thijaba (In Search), Takpiri Nahakna Khudamna Uttuna (You Teach with Symbols), etc. amply show the extent of influence he received from Vaishnava faith and they show his devotion to god. These were poems written under the influence of Vaishnava dharma.

The hard working nature of his father Thabal Singh and mother Sinam Ningol Angangjaobi ran in Nabadwipchandra1s veins profusely. His father Hawaibam Thabal Singh was once a favourite of Maharaja Kulachandra (1890-1891) and he was placed in charge of the lallup. In those days every able bodied male from the four panas of districts used to work ten days for the king and forty days for themselves. During this ten days, they had to feed themselves too. This is known as the system of lallup. Thabal was a hard working person. He used to go the countryside for two three months at a stretch to join harvest. His mother was renowned as a weaver – a fine cloth manufactured by her which was called Chakhrangtabi was very much sought after in the market. Their son had inherited both the hard working nature and fine artistic talent from them. People are of the opinion that were Oja Nabadwipchandra not a disable person, there is no reckoning how he could have been controlled.

Nabadwipchandra was a much talented person. As a poet he possessed an inborn quality. His mind was very sharp and artistically tuned. While he worked in his garden, he always kept pen and paper with him. If the urge comes, he would throw down everything and start writing. By nature, thus, he is a true poet. He sincerely loved his mother tongue and always concentrated his mind on how to develop his own literature.

The flame of literature which was kindled during the early half of the twentieth century is a matter of pride for the Manipuri. New ideas on different subjects, the search for identity and own culture, remembrance of old transitions, the arrival of the inspiration to serve the motherland, renewed love of the long derided mother tongue are the main characteristics of the renaissance which took place during this period. On the frontline were such poets and literatures like Kamal, Chaoba, Anganghal, Dorendrajit, Parijat, Irabat, Lalit, Ibungohal, Minaketan, to mention a few. Nabadwipchabdra was one of them.

Despite the variety of the course followed by the renaissance poets and writers, one could find common elements among them as they happened in some way to belong to the same period and time. The speed and force of this movement was much delayed due to the lack of popular support, educated people and of consciousness among the people. That is why the renaissance in Manipur could not see the acme of achievement. In beginning, literary organizations and political parties were not there. The first literary organization – Manipuri Sahitya Parishad was established in 1935 and the first political party Nikhil Manipuri Mahasabha in 1938. Leaders were hard to find before as the would be rebels were almost all near relatives of the king and employed under him. Hence the difference seen between the renaissance of Bengal or other states and that of Manipur.

We may briefly put into three groups the movements during the early decades of the twentieth century – 1. Political movement, 2. Educational movement and 3. Linguistic and literary movement. The state administration was under the king and the Durbar. In the 1930s Jananeta Irabat commenced to protest against the systems of political and religious bigotry. Rajkumar Birachandra Singh led a group of people to establish Mother Club which imparted learning and gave education to those students who could not get admission in the Johnstone School. People became more aware of the need to establish educational institutions. A committee was formed to start “Manipur Institute” at Waheng Leikai in Imphal which later became the C.C. Higher Secondary School. At this time another Sanskrit Institute “Govinda Chatuspathi” added English as a subject in their syllabus and was renamed “Your High School” which later became the present Tombisana High School at Imphal. A move was started to establish a college in the state from 1932. It paid dividends when classes started in 1946 with the coming of the Dhanamanjuri College as a night college.

On the other hand, linguistic and literary movements coursed slowly. For in such matters, resolutions are not much help as things cannot be changed or brought into existence overnight. The change would be apparent when the writers of the soil disengage themselves from the influences of the Bengali language and its inherents which had been keeping them charmed for a century or so. As such this kind of movement is fully dependent on the would be writers and Manipuri language and literature had to wait for them. The number of writers in those days was much less. Dr. Kamal wrote of this in the introduction to his novel Madhabi in 1930 – The Meiteis are not yet captivated with the sharm of writing.

There is inseparable relationship between the two movements of language and literature. The earlier period was fully dominated by Bengali literature. Bengali words were much in use even in day to day life. Such fanatics were there who even thought it sacriegious to us. Meitei words in public occasions. It was during such a period that a handful of writers among whom Nabadwipchandra was one, came out boldly and started writing in their own language for their literature. Nabadwipchandra’s Haksel, Dwijamani Dev’s Wamachang (The Substance) and Chaoba’s coinages and expressions were regarded in that period as new found wealth. These writers used to meet and consult frequently to discover ways of effective organizations. In the Uripok area of Imphal where both Chaoba and Nabadwipchandra were born – Chaoba is supposed to be elder to the latter by about two years – these two poets along with another person, Thiyan lbohal Singh, used to sit regularly after work at the house of Dwijamani Dev Sharma who was a Deputy Inspector of Schools in those days. Nabadwipchandra as a habit stopped at the utensils shop of one Bengali, Rameshchandra by name at Waheng Leikai and Amade Sharma’s house his next stop.

Slowly but steadily Meiteilon started experiencing a renewed flow. In 1905 the famous artist Bhadra Singh was asked to paint the legend of Khamba and Thoibi and the myth of Dasavatar on the walls of the Cheirap Panchayet Building. These acts showed the interest taken towards the revival of Manipuri culture and arts. In 1917 the British asked Haodijam Cheitanya to write in prose the story of Khamba Thoibi to further supplement Manipuri literature and subsequently the book got published. In 1919 The Maharaja Churachand Singh organised a Gouraleela before the temple of Shri Govinda and participated himself as the main singer. Strange as it might have appeared in those days, the leela was performed and the songs sung from beginning to end in Meiteilon. Next a Raasleela was performed in Meteilon. During 1915-16 Khaidem Nongyai and Phurailatpam Bidhu introduced Manipuri holi songs. Later on, two holi groups – one was Johnstone School and the other, of Kangabam Leikai – became very popular. In 1916 Khaidem Nongyai who was a teacher in the Johnstone School translated the Bengali play Parthaparajai into Manipuri and brought it out on stage. It gave a strong impetus to the public. In 1924 Manipuri became one of the vernacular subjects in the Entrance Examination under Calcutta University.

The staging of the first Manipuri original play Narsingh by Lairenmayum Ibungohal in 1925 was considered a public event of significance. By the year 1938, the Manipuri Shitya Parishad had started demanding the recognition of Manipuri as a major Indian language. The chain of events shown in this way indicates the gradual development of the movements in the field of language and literature. Churachand Maharaja’s contribution in these matters are enormous. He took keen interest in games and sports as well as arts and culture. It was due to his royal patronage that such significant changes had been brought rapidly. Manipuri writers, on the other hand, did not remain silent. They continued writing books and producing journals on their part.

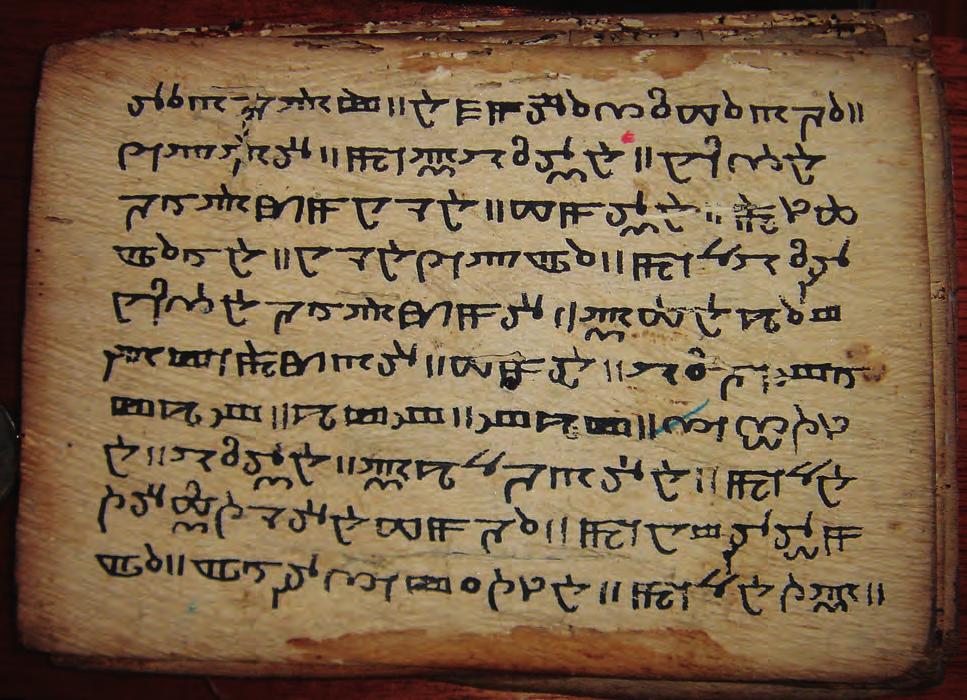

The first Manipuri hand-written journal Meitei Chanu edited by Hijam lrabat was brought out in 1922. In quick succession there appeared other periodicals like Yakairol (1930), Deinik Manipuri Patrika (1932), Lalit Manjari Patrika (1933), etc., before the advent of the second world war in Manipur.

Those periodicals regularly published poems, essays and other prose works by the pioneer renaissance writers. The first number of Yakairol edited by Dr. Leiren published Nabadwipchandra’s poem Sri Saraswatibu Khurumjaba (Prayer to the Goddess Saraswati). Many of his poems were also published in other journals – Meitei, Ngasi Thakhaigi Chephong, etc., for instance. Kavi Nabadwipchandra who had also taken active part in establishing the Manipuri Sahitya Parishad and many other associations worked heart and soul to revive once agajn the downtrodden Manipuri language and literature. His poem Punsi Hidom (The Solitary Boat of Life) clearly manifests the taunts and jives suffered by them when they were trying to resuscitate back to life their own language and literature. He wrote about it thus in the poem – “People on the river banks shout/Steer it you madcap/as close to the banks as you call/why do you sail without the skill!”

Kavi Nabadwipchandra had been honoured with Sahitya Ratna by the Manipuri Sahitya Parishad in 1948 posthumously and his service to Manipuri literature and language is great indeed. He translated the first five cantos of Michael Madhusudan Dutta’s immortal epic Maghanad Badh Kavya under the title Maghanad Tuba Kavya with the express purpose of fulfilling the need of text books for B.A. students. Not only did he make a new gift but also served the literature with his presentation of the highly sanskritised Bengali of Madhusudan in simple and lyrical Manipuri. It proved his merit as a great translator. We find again the typical Nabadwipchandra and his quality as a poet in many of his poems written before the execution of the translation. He left us a new kind of diction – without artificially, based on simple words used in ordinary transactions. But these were nevertheless capable of carrying lofty sentiments. He even went to Moirang, a culturally rich place, in order to acquaint himself more with its legends and when he came back wrote a long poem Tonu Laijinglembi. Like Kavi Chaoba, he also uncovered lost or forgotten literary materials once again. Nabadwipchandra truly is a flower of the renaissance in Manipur. The depth of Bengali literature as well as western education and influences commingled with traditional elements in him and with the help of this new kind of sensibility, he shared with a great degree of success the pioneering works of creating a modem Manipuri literature during the first few decades of the twentieth century.