Even if the current crisis of ethnic strife were resolved, one still would shudder to think where Manipur might be heading. The course could change and hopefully it does, but if it doesn’t, it is difficult to imagine what the place would be like in another two generations. For one, the economy is just not generating enough jobs. Those few that are, have been rendered facile by a disproportionately protected and compensated government jobs with the result that everybody today wants a government job and nothing else.

Traditionally, non-government professions were beginning to multiply in Manipur, especially in the valley area. Meitei surnames will testify that blacksmiths goldsmiths, mechanics, masons, carpenters, tailors, farmers, horse tenders, poultry keepers and many more were becoming vital services and the backbone of the place’s revenue generation machine. Today these professionals would sell their professional wares to have enough money to pay the bribes needed to get their children garner even a Grade-4 government job and not be trapped in the professions that their families practiced and honed for generations.

Indeed, every time the government advertises for jobs, such as police constables, you would begin to hear of farmsteads and homesteads going for sale. This would not have been so bad if the government was in a position to provide jobs to all job aspirants, but this can hardly be, given that even the 80,000 or so that the government directly employs today have already hit the ceiling of the government’s capacity to sustain, or needs. There are plenty of redundant employments already, as is loudly visible in any given office where employees are generally seen loafing around or else away from their offices for extended periods. There are also numerous government schools and colleges which have only teachers and staff but no students to teach.

This redundancy of workforce can also be gauged if one were to imagine what the scenario would have been if the Manipur government were to be run like a private enterprise, strictly getting the optimum out of each worker and paying as per the contribution of each. In all probability, half as many government employees as currently employed would have done a better job to run the state.

Just imagine this. Somebody who owns one or two freight trucks or passenger buses would be considered rich by the state’s standard. Why then did the MSRTC which on the average owned 200 such vehicles at any given point, end up an abject failure? This dirge for traditional professions and the reciprocal craze for government jobs are slowly reducing the profile of the state to a dreary monotone, swarming with hierarchies of government servants and government contractors. At some point the question as to what is being served by this gigantic service sector when the social enterprises they are supposed to be serving have been dwarfed or else eliminated, will become unanswerable. How can such an economy ever grow and save itself from being condemned to an eternity of parasitic existence? It is only some exemplary entrepreneurship which has now begin to ensure some professions to be able to remain autonomous of the government, and continue to pull along amidst all these odds.

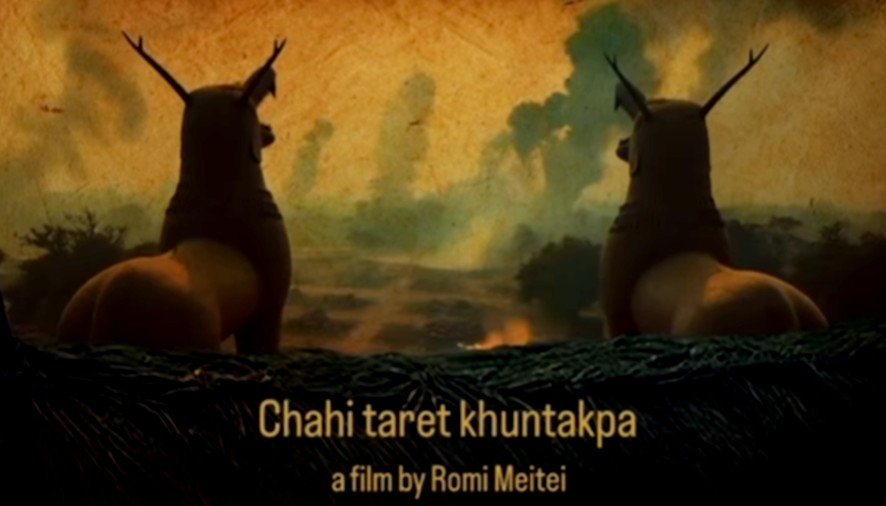

Manipur must be entering the cataclysmic end of an epoch that so many religions predict. At the end of every epoch, according to these beliefs, the world is consumed by its own violence and misdeeds, and then from the resultant debris and ashes, it rises again in a new incarnation like the sphinx. In Hinduism the notion of Yug says this. But no other religions have it more distinctly than Christianity with its prediction of the Apocalypse and its horsemen with a mission to raze everything of the old world order to the ground so that a out of the debris can sprout a brave new world.

The imagery is arresting and many poets fell for it, including Irish romantic poet WB Yeats who uses it with such gripping power in “The Second Coming”. Hence at the fag end of an epoch, “mere anarchy is loosed upon the earth” and “things fall apart” before civilisation regenerates. Reminiscent in this imagery of death and rebirth, destruction and regeneration, ironically is the notion of revolutionary creativity. Hence, certain institutions and deeply institutionalised social evils (corruption for instance), are beyond reformation and have to be destroyed violently and the foundation of a new society built over their ruins. Krishna’s sermon to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita also is very much about this understanding. But this argument can boomerang in the absence of moderation by an interlocutor such as Krishna in the Gita. For then the idea of revolutionary creativity can begin to mean only destruction without creation. This idea of creative destruction is encapsulated so well in the Manipuri proverb: Chairen chaphu thugainaba phuba natte (Potters of Chairen hammer their pots not to destroy them but to create them)

A vital cord has snapped in our society and it is losing its sanity. A society is able to keep on the tract of sanity precisely because human behaviour is not grossly inscrutable and unpredictable. Hence, we know for instance murders do not happen without tangible reasons or motives. We also by and large have faith that children would normally be not subject to murderous attacks, or that hospitals and schools by civilized consensus would remain as conflict free zones. Such sacred civilizational threads knitting our society together have today become lost. You no longer are sure if hospitals or schools are safe, whether bombs would go off in crowded market places, or meaninglessly somebody would be shot in cold blood as a demonstration of cruel destruction potential to send terror in the hearts of others and bring them under the will of the perpetrators of these violent acts.

The obvious result is all round insecurity. Dissenting voices have been made the first casualty and now even beyond this it is a regime of what George Orwell called “thought policing” that has gripped our society. Sadly, no government, not just this one, has ever recognized this danger staring at all of us today.