By Reece Hooker, 360info

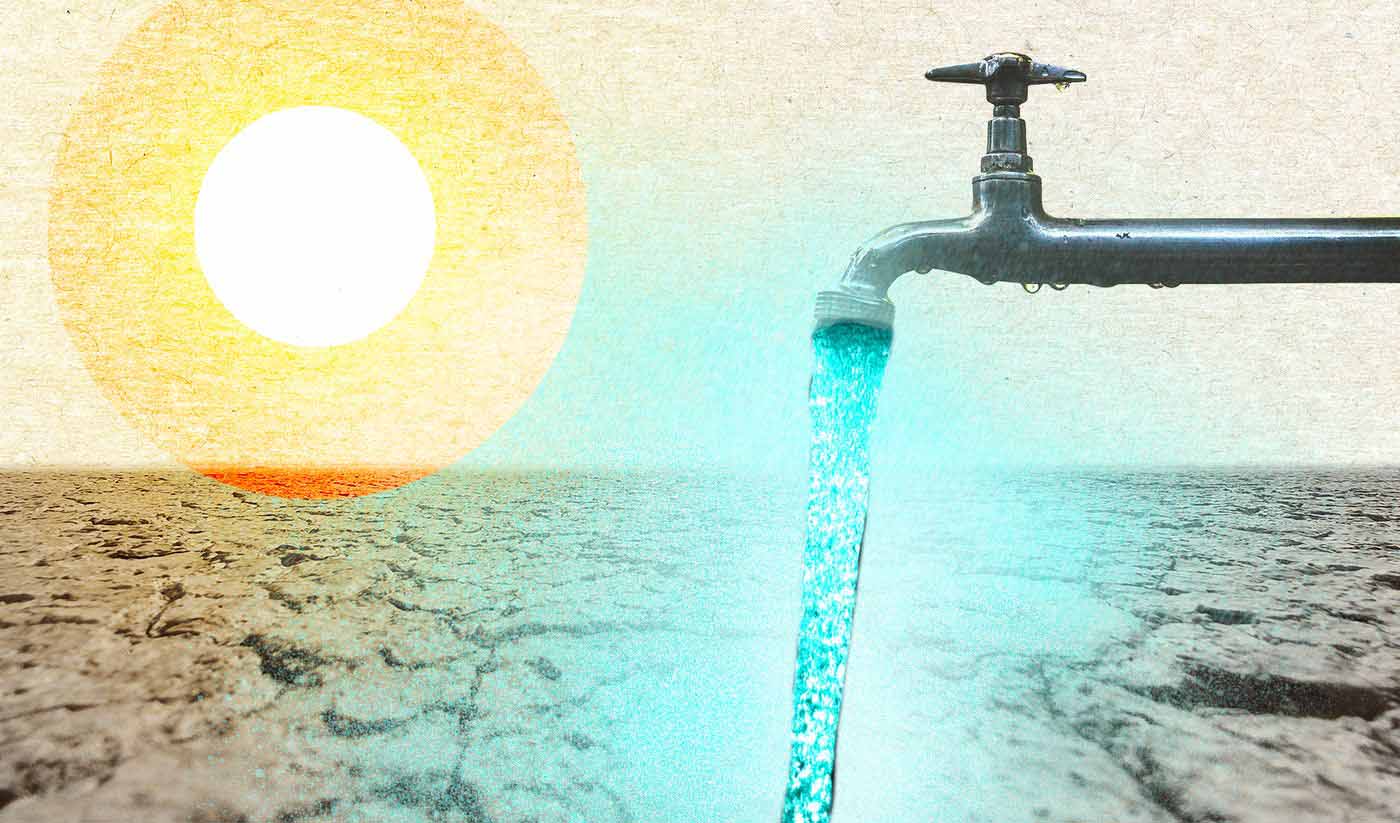

Tensions around access to and management of water are heightening all over the world. Finding ways to de-escalate and innovate is a matter of life and death.

The world is facing a water crisis. Four billion people — almost two thirds of the world’s population — face severe water scarcity for at least one month each year. By 2030, experts predict that demand for fresh water will outstrip supply for 40 percent.

Heightened scarcity prompts a higher propensity for conflict. As we face a future where some parts of the world will be chronically short of water, so too comes the increased risk that groups will be drawn into conflict and wars over access to and sovereignty over water.

But water conflict isn’t just a risk of the future, it’s happening before us now. In February 2024, Israel confirmed it was pumping seawater into a network of tunnels in Gaza, claiming it was “neutralising underground terrorist infrastructure”.

But the action “will definitely” contaminate an aquifer holding Gaza’s groundwater, imperilling Palestinians already facing bombing, imminent famine and a death toll exceeding 30,000.

With this backdrop, the UN is commemorating World Water Day with the theme ‘water for peace’. It brings to light not just the conflicts raging over water in the present, but pathways to resolution.

Conflict takes many shapes and forms. While the weaponisation of war in Gaza presents the most imminent threat to human life, other major water struggles happen more gradually — diplomatic disputes and bureaucratic arm wrestles have cause immense friction in major waterways, such as Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin and Malaysia’s Johor River.

The management of the Murray-Darling Basin is a “cautionary tale of what and who can get in the way of good practice and how reform can, sometimes, go backwards, as well as forwards”, according to Quentin Grafton of The Australian National University.

“On paper, it doesn’t make sense: Australia is a stable democracy with a robust public service. It could be a model case study of sustainable river management. Instead, it has been derailed by dispute and bureaucratic in-fighting.”

This is not uncommon. As Shafiqul Islam of Tufts University notes, “blame shifting, fault finding and panic” are “the usual reaction to water crises all over the world.”

To reverse the trend of water scarcity, reform will have to move quickly and comprehensively. From finding ways to end the use of water as a weapon in conflict to foster stronger cohesion in river management to innovations that help maximise the remaining water supply we have left, bringing peace around water is an ambitious but vital challenge for the world.