The Myanmar civil war, triggered by the February 1, 2021 military coup has crossed the four-year mark. There is however still no sign of a respite from the anarchy the country is in. Adding to the country’s misery now is the devastating earthquake last week, the death toll from which has already exceeded 1600 on Sunday, and is expected to climb much higher as the entire picture becomes clear.

The earthquake devastations will for now understandably divert international attention from the civil war but in the days ahead the tragedy will probably accentuate the acute divisions this country of multiple ethnicities is cursed with, when it becomes evident that the government does not have the means to mitigate public misery from the calamity.

The country’s economy is already stressed to breaking point by the civil war, and therefore it will have to depend on the generosity of the international community to overcome the new challenge. It remains to be seen if politics colour the response, and how many countries get to set aside their disapproval of the military junta to extend humanitarian aid.

One scenario is almost predictable. China will be among the most indiscriminate in offering help to the junta, not for any particular liking of the latter as often alleged, but to ensure its deep interest and matching investments in the country are not upset. It is for this that China has always made it very clear that it will ally with anybody in power in Myanmar, and indeed, while Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, NLD, was in power after the 2015 election, China also rolled out the red carpet for Suu Kyi.

China has also not abandoned other backup plans in case its Plan-A of winning the confidence of whichever party is in power in Myanmar runs into rough weather. This is clear from the influence it cultivates and maintains on several powerful Ethnic Armed Organisations, EAOs, especially in the Shan and Kachin states bordering China. This fine strategic balance was seen at play in the manner China brokered a ceasefire between the junta and The Three Brotherhood Alliance in northern Shan state, an alliance of three EAO which had inflicted some serious reverses on the junta.

These three EAOs, are the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, MNDAA, of the Kokang people, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, TNLA, of the Ta’ang people, and the Arakan Army of the Rakhine people. The picture is clear. China prefers a partnership with the party in power in Myanmar, and in winning such a partnership, its influence over Myanmar’s many EAOs, has been an effective bargaining chip.

China, it may be recalled, was also one of the prime movers behind the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement in Myanmar on October 15, 2015, at the national capital, Naypyidaw, a month before the country’s general election which saw the return of Suu Kyi’s NLD to power. Of the 15 EAOs invited only 8 ultimately agreed to enter into the agreement, although two more joined in February the next year, again under China’s influence.

But aligning with the party in power especially during a civil war must have to be a delicate and sensitive balancing act, for it can generate negative sentiments among those opposed to the regime directed at whoever makes such a move, and China is already sensing this to a considerable extent.

This being so, reports from Myanmar indicate that China’s pressure is again a factor in coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing, who is now the chairman of the Junta’s State Administrative Council, SAC, deciding to fix Myanmar’s next election this December. The hope is this will bring back a certain degree of legitimacy to the country’s government, and therefore the return of peace and political stability.

It is quite obvious, Myanmar in anarchy hurts China’s interest, but a splintered Myanmar where it would then have to deal with several statelets to protect its interest cannot but come across to it as a diplomatic and strategic nightmare. This is especially so considering the possibility that some or several of the new states may not be favourably disposed to it and may become the entry points for rival powers opposed to it.

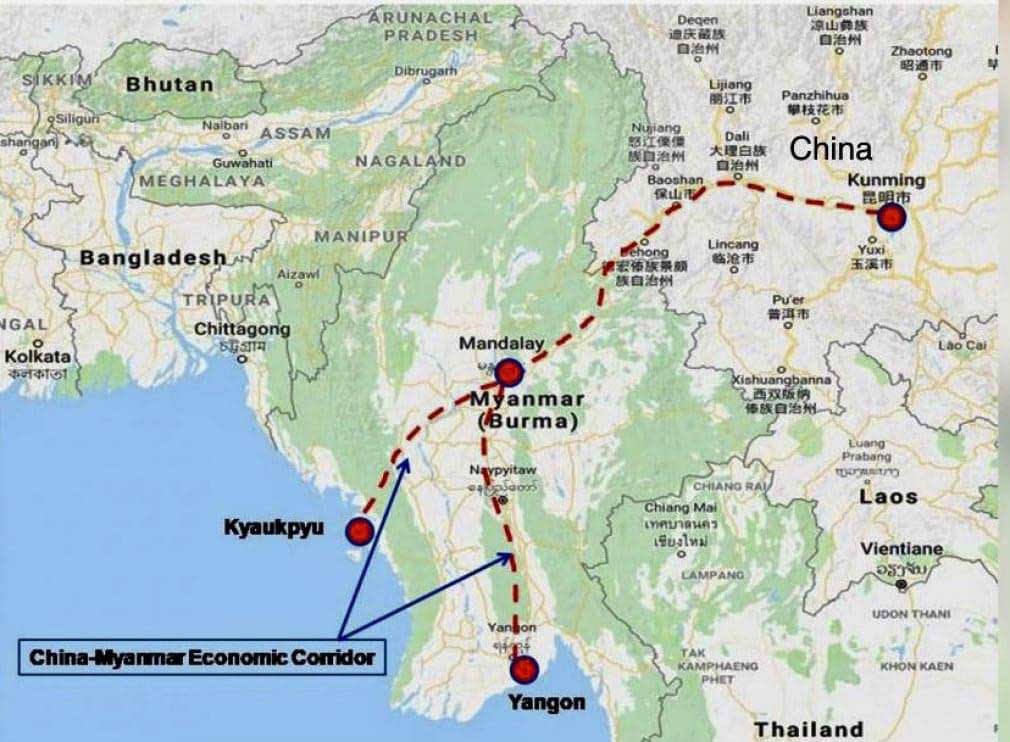

China’s interest in Myanmar goes much beyond the resources that Myanmar offers directly, copper, jade, rare-earth, hydroelectric, to name just a few. It is more about a land access to the Indian Ocean, and from there to Africa where its investment is expanding and the oil rich Arabian peninsula. This anxiety is often described as China’s Malacca Straight dilemma, which currently is its only and much detoured sea route to the Indian Ocean. Moreover, countries around this straight do not come under China’s sphere of control. China already has an oil and gas pipeline from Myanmar’s Kyaukphyu deep sea port in Rakhine State to Yunan Province, transporting crude oil and natural gas directly to China directly.

With its rivalry with India unlikely to deescalate in the near future, Pakistan and Myanmar remain China’s most viable land routes to the Indian Ocean. While both these countries have friendly ties with China, Myanmar is the preferred route. First, the Karakoram passes are far more rugged. Second, before the February coup, the territories in Myanmar this route passes through were much more stable than Pashtun and Baloch frontiers in Pakistan.

China’s growing influence in several Indian Ocean littoral nations however is leading to the emergence of a new geopolitical theatre in the region. India is legitimately concerned by the development and indeed American geostrategic researcher Virginia Marantidou in a 2004 paper claimed this was China’s ‘string of pearl’ strategy to encircle India to undermine it. China’s entry also predictably drew in other China wary powers into this theatre. The revitalisation of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, Quad, a strategic forum of four nations, United States, India, Australia and Japan is one evidence.

Likewise, no less a person than ousted Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, had charged that certain Western powers had a hand in the trouble in her country and neighbouring Myanmar. But these are interesting times. The return of Donald Trump as US President is already causing unexpected changes in familiar geopolitical order. As in Ukraine, this geopolitical theatre too may yet see complete makeovers, for the good or bad.

This article was first published in The New Indian Express. The original can be read HERE