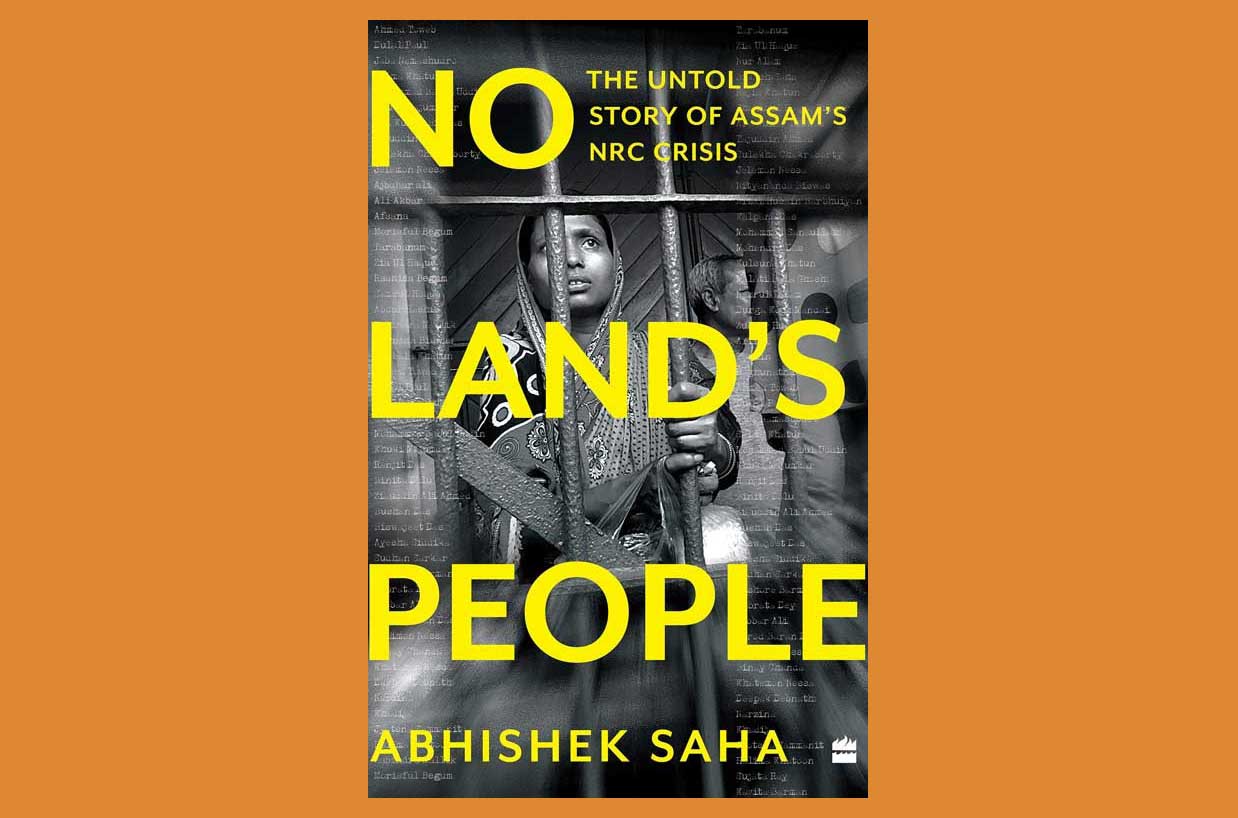

Book Title: No Land’s People: The Untold Story of Assam’s NRC Crisis

Author: Abhishek Saha

Publisher: HarperCollins

Price: Rs 599

This book is a collage of updated reportage by a newspaper correspondent chronicling the controversial exercise of identifying and segregating illegal migrants in Assam, a land that has been the recipient of massive and continuing migration since colonial times from neighbouring Bangladesh — once Pakistan — and, before that, East Bengal, for reasons political and economic. Whatever the compulsions and urgencies fuelling the need for this exercise, its tragic human costs were predicted by many. Here were millions of people, who had been forced to migrate by circumstances beyond their control to make Assam their home for decades, being uprooted and made Stateless. The irony could not have been starker than in the sombre epilogue to the book where the author — he also reported on Kashmir during the violent unrest after the death of the Kashmiri insurgent, Burhan Wani, at the hands of the Indian army — makes a comparison of the two experiences. While in Assam, people desperately wanting to be classified as Indians were being heartlessly excluded, in Kashmir, Indian citizenship was being brutally forced down the gullets of a sizeable section of people stubbornly discarding this identity.

Saha does well to portray the magnitude of the human tragedy caused by the National Register of Citizens enumeration but falls short of putting this tragedy into the larger context of Assam’s besieged history since colonial times, which, slowly but surely, led to the present cataclysm. He approvingly quotes scholars like Sanjib Baruah, who have said that the NRC exercise was necessitated by a unique turn in Assam’s historical experience, but this necessity has since been made monstrous by a dispensation professing a majoritarian ideology. What prompted the NRC exercise was the culmination of a complex and multi-layered action-reaction equation of a constantly interchanging victim-and-perpetrator situation. This book, constrained by the compulsions of racy reportage, tips the balance towards the immediate and the urgent: the immense, heart-shattering predicament the NRC put numerous helpless individuals in.

What the readers are also reminded of is the old triangular rivalry, first between the linguistic nationalism of the Assamese and Bengali-speakers. A second dimension was added to this with the growth of conflicting religious nationalism between Hindus and Muslims in the Indian subcontinent — the migrants from Bangladesh being speakers of Bengali were of both faiths. Because of the nature of the friction in Assam in the face of this peculiar past, the state had seen an earlier NRC in 1951. The book shows — quite convincingly — how flawed and unreliable the 1951 NRC was. The present NRC, the final report of which became ready in 2019, is an effort to update the former against the backdrop of unrelenting pressure from Assamese organizations insecure that they may lose their land and handles to State power in the face of what they believed was an unceasing tidal inflow of alien population into the state. The climactic point of this anxiety was the Assam Agitation of the early 1980s, which led to the signing of the Assam Accord of 1985.

Readers are given a sense of the enormity of the NRC and its proneness to flaws, on its own as well as on account of the fact that it was to draw on flawed past records of the 1951 NRC — electoral rolls and decadal censuses — and not entirely on data gathered through door-to-door surveys. Saha digs up cases where entire families were brought to ruin because of bureaucratic lethargy and clerical errors in name and date of birth entries. Through interviews of victims, Saha reminds readers how there was always a nuanced and sometimes blatant bias against Bengali-speakers, especially Muslims. Adding to the intimacy of these stories is Saha’s grandmother — she had no reason to be denied Indian citizenship — who came to be excluded from the NRC.

The nature of the mission before the man chosen to lead the NRC project, Prateek Hajela, a technocrat by training but bureaucrat by profession, was nothing short of intimidating. It involved having to calibrate the citizenship of close to 3.3 crore people through officially-prescribed documents. It also meant having to digitize 6.25 lakh pages of the 1951 NRC records, 35 per cent of which was already lost or rendered illegible by wear and tear. He was also to come up with a list of approved legacy documents by which people were to prove their citizenship while dropping others that are deemed to be prone to manipulation and forgery. In a country where birth and death certificates are not taken seriously, the impossibility of the task at hand is imaginable. There was also the question of methods to handle appeals by people excluded and objections by others against excluded people.

The unenviable fate of Hajela at the end of the exercise, reviled by those at the receiving end on the basis of suspicion of siding with Assamese nationalists as well as by the latter for being too lenient on those they suspect are illegal infiltrators, reflects the sensitive nature of the job as well as the knife-edge balance he and all others tasked to execute the project have had to keep.