Once in a while Indian film festival circuits are bowled over when extraordinary stories from the Northeast region make their appearances. Starting from 2016, the region has had a significant run cinematically.

Pradip Kurbah, a filmmaker synonymous with Khasi cinema from Shillong, Meghalaya made headlines with his latest work, ‘Lewduh’ (or Market in Khasi), premiering at 24th Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) 2019, a rare and prestigious feat. The 94 minute film is about the lives of everyday people and their stories, shot entirely in a crowded market, the oldest and largest traditional market in Shillong. The Busan Festival held annually in South Korea is big and for the two times national award winning filmmaker (RI: Homeland of Uncertainty, 2013 and Onaatah, 2016) it is the icing on the cake of his filmmaking career.

Before Kurbah, another big achievement by another filmmaker from Northeast grabbed limelight with her extraordinary film, ‘Village Rockstars’. Mumbai based Assamese filmmaker, Rima Das’s film is about a 10-year-old girl from a small village in Assam who dreams of owning a guitar and forming a rock band. “A young girl and her mother’s woes and misery are not music to the ears but their spirit is,” reads the synopsis of the film. Through masterfully captured sights and sounds of Assam, Das shed light into Dhunu’s world of dreams and responsibilities. While the film takes on the dilemmas of poverty, the tone and theme of the film is never tragic. At a deeper level it becomes a heartening tale of courage and pursuit for happiness. For a film coming out from Northeast region, it broke all records. It did exceptionally well at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 2017 and then went on to become India’s official entry to the Oscars 2019 in the ‘Best Foreign Language Film’ category – a feat unlikely to be broken any time soon. Imagine, a film from Northeast, representing India in the Oscars! Of course it won hordes of other trophies and awards, including the National Award for Best Film for 2017.

A year before Rima Das’s amazing feat, Manipuri filmmaker, Haobam Paban Kumar was the Northeast India’s torch-bearer with his reality drama, ‘Loktak Lairembee’ or Lady of the Lake in 2016. Shot entirely on the scenic fresh water lake of Manipur, the 71 minute film tells the existential crisis of a fishing community living on the Loktak lake in the backdrop of an eviction drive and an elusive on-going armed conflict. Amidst this situation, “a depressed fisherman” accidentally finds a gun and “transforms himself to an assertive man who begins to believe that the gun would solve all his problems.” Not only did ‘Loktak Lairembee’ feature in 21st Busan International Film Festival 2016 in the Asia New Currents category, it was a ticket for Paban to the Berlinale Talent at the Berlin film festival 2017. Beside participating and winning several awards, Paban Kumar’s ‘Loktak Lairembee’ won the Best Film on Environment Conservation/Preservation in the 64th National Film Awards in 2016. This was the first Manipuri feature film that won a national award in a category other than the best Manipuri feature film category.

What is significant is that stories such as Pradip Kurbah’s, Rima Das’s or Haobam Paban Kumar’s are not at all rare. It is fairly easy to stumble upon many more unique untold stories of the region. Unfortunately, the region is marred with unfavourable climate for production.

“Turbulent political climate is the least of the problems,” says Delhi-based Assamese award winning filmmaker and film critic Utpal Borpujari. “It’s quite peaceful now. The issue is lack of funding and public spaces to screen films. Even in a state like Assam, where there is a potentially huge viewer base of Assamese cinema, the number of halls is pathetically low. Add to this the fact that most films get just two shows per hall per day and many get just one show.”

Another worrying issue is the low-quality content of most films produced in the Northeast, particularly from Assam and Manipur, the two states that top production in the region.

“In recent years, barring a few exceptions, mainstream cinema in both states have become caricatures of B-grade Hindi or Telugu movies, which follow a set formula of a few song and dance routines, some fight sequences, over-the-top-acting, held together by a flimsy storyline,” says Borpujari, the director of Ishu, a children film which won the National Award for the Best Assamese Film in 2017 along with six Assam State Film Awards and four at the Prag Cine Awards in the same year.

Meghalaya based filmmaker, Wanphrang K Diengdoh feels the cinema of the region is trapped by stereotype. “Filmmakers of the region, in general, are forced to carry or rather enjoy the self-flagellation of creating visual content that is either related to militancy, traditional anthropology, tourism and the general image-making that attempts to make an exotic facade of the area,” says the Khasi filmmaker whose latest film,“Lorni-The Flaneur” departed from the stereotype and explored the identity of cinema from Meghalaya. Diengdoh’s film is about an out-of-work-detective protagonist, played by Adil Hussain, Bollywood star, trying to track down ‘stolen objects’. Shot in the rain-bathed Northeast hill station of Shillong locales with the vibrant street music and a blend of English, Hindi and Khasi as its language, the film weeps into the darkened lanes and alleyways of Shillong.

Another filmmaker from Meghalaya echoes the similar sentiment. “I hate the exoticization of the Northeast. It’s very sad that Northeastern films or filmmakers are clubbed together as if ‘Northeast’ itself is a state,” says Dominic Megam Sangma whose latest Garo fiction film, ‘MA.AMA’ is on the true experiences of his father. Sangma took more than five years to prepare himself to write the script for ‘MA.AMA’, which involved intimate conversation with his father about his past.

This sense of alienation had extended to one of most mainstream production in recent times from the region, ‘III Smoking Barrels’. Directed by Mumbai-based filmmaker, Sanjib Dey, the film ran into trouble with the Censor Board as it features six different dialects from Assam. Incidentally the term ‘multilingual’ wasn’t in the vocabulary of the Central Censor Board. “My film has received the certificate of an English-language film when I’ve barely used a smattering of the language,” says Dey.

While many agree to the patronizing attitude of the mainstream towards films from the Northeast during most State-run festivals, they argue that these have not helped the cause of cinema in the region by impeding originality in creation. National award-winning director, Bhaskar Hazarika feels that film festivals however help channel a certain kind of nuance around Northeast cinema. “Northeast-special film festivals are of great value because filmmakers find avenues to exhibit their work outside the NE,” says Hazarika whose latest work, ‘Aamis’, a love story set in Guwahati, secured funding at Busan’s Asian Project market.

Arunachal Pradesh filmmaker, Sange Dorjee Thongdok says if it weren’t for the film festivals, independent films would confront immense problem in recovering the cost of production. “In this age of digital media, it isn’t very difficult to make a film. Marketing and distribution, however, is a whole different ball game, particularly for independent cinema, which doesn’t get much support anyway. It becomes extremely difficult to recover the cost of making a film if there is no support for distribution or screenings,” said Thongdok, the first filmmaker to film in Sherdukpen dialect. A graduate from Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (Kolkata), ‘River Song’ is Thongdok’s second production about a boy who stubbornly refuses to leave his home as his town is getting submerged in water from a dam being built nearby. Thongdok first film‘Crossing Bridges’ the first film in Sherdukpen, his mother tongue, won the National Award in 2014.

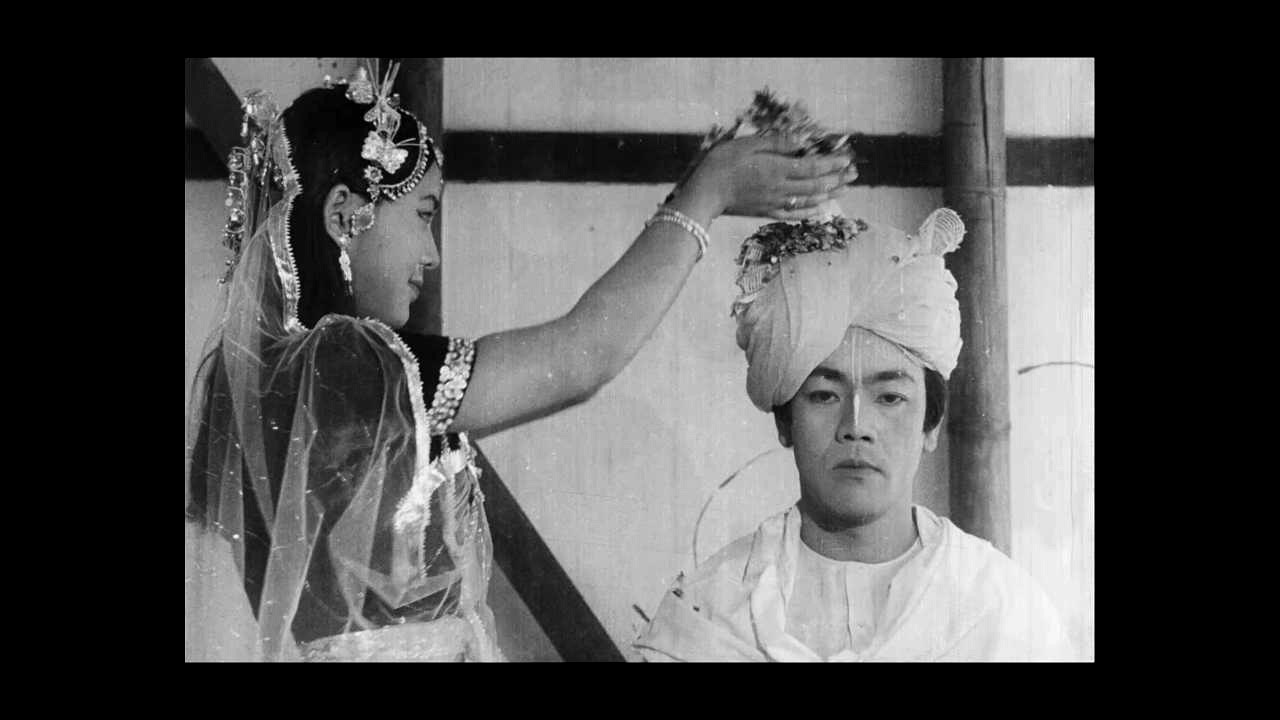

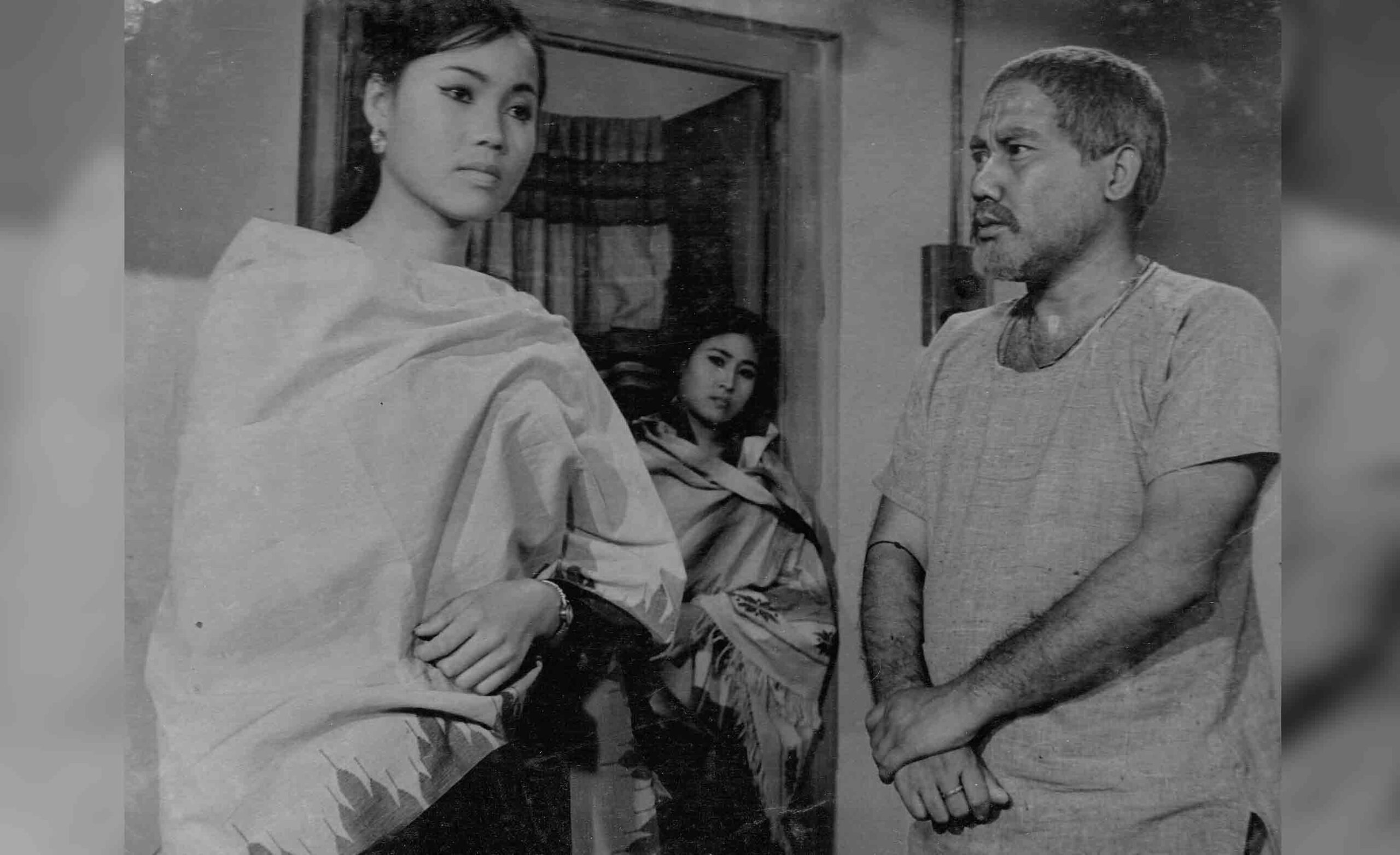

Another issue troubling the film industry in Northeast region is the shortage of movie theatres. Bona Meisnam, a filmmaker from Manipur complained that he can’t watch most of the latest Manipuri films. “After movie theatres shut down one after another following the ban on Bollywood films by a proscribed underground outfit, there is literally no movie halls where one can go and enjoy a film!” said Meisnam who is currently making corporate films. This sentiment of shortage of movie theatre gets louder with the recent successes films from the Northeast in the international festival circuits. Significantly, the first film to be produced in Assam in 1935 called, ‘Joymoti’, directed by noted Assamese writer, poet and filmmaker, Jyoti Prasad Agarwala, had to be released in Kolkata since there were no halls in Assam at that time.

While movie pundits and film critics say the movies are currently going through a “reverse trend” with abandoned movie theatres and the concept of home theatre on the upswing, alternate spaces for cinema have come into the picture with online streaming ventures like ‘Movietonne’.

A streaming site for Assamese films has set an amazing example in terms of reach at a cost of ₹40 per movie. “We looked at platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime and knew that we wanted to provide an online movie streaming platform to display our own regional stories,” says Manas Pratim Kalita, the engineering student who is expanding his platform to cover documentaries and shorts, apart from films from Manipur and Meghalaya.

Another silver lining is ‘Aaideo Talkies’, the travelling cinema initiatives which is disseminating stories from the region. It is an experiment that started around six years ago by a group of young people. The latest model of travelling cinema halls have satellite projection systems, 5.1 sound quality and even air-conditioning, thus enabling the viewer in even a remote location without access to an actual cinema hall to experience a city cinema hall-like experience to some extent. This concept is fuelled with the principle to take cinema to the audience if the audience can’t come to see them for some reason or the other.