The hunt for a conclusive answer to the periodic waves of frictions between different ethnic communities in Manipur must not be abandoned. The current flashpoint, brought about by a claim of gross, persistent and systematic official policy bias in favour of the valley and at the cost of the hills is just one of these, and it is tragic that this has already resulted in the brutal assassination of a courageous voice which called the bluff in these allegations and instead advocated the necessity for peaceful co-existence of all communities, and if there are discrepancies in the administrative structures, to address them rationally rather than communally, to ultimately work towards an equitable resolution by consensus. One of the questions which is often relegated to the blind spot in these unseemly tussles is, what exactly is development? Is it about institutional buildings sitting in anybody’s neighbourhood and the belief such a neighbourhood would automatically benefit more from this? For instance, would the Manipur High Court located at the base of the Langol Hills have benefitted the communities in the area more than others? Would the poverty and unemployment problems in the area have been addressed better than other parts of the state by this fact? As a matter of fact, each time any piece of land was earmarked to be developed as such an institutional premisis, the pattern has been for the locality to protest but khas land being government land, these protests seldom held for long. This can be said of most or all other public institutional infrastructures anywhere. Alternatively, should development be ultimately about administratively addressing everyday human problems – gainful employment, livelihood means etc., in the hierarchy that Abraham Maslow proposed? Have there been any such initiatives, and if so, were there hill-valley discrimination in their execution? These should have been the more relevant questions asked in any bias assessment. In a way, the current flashpoint, and the supreme sacrifice made by a courageous leader, brought some of these discussions to the fore of public space, and in the process had redemptive effect on many fallouts of the curse of communalism in the state. Many of us participated actively in these discussions, and suggested ways out of the unenviable quagmire the state has been trapped in for so long, and our own stand has been for exploring the possibility of a comprehensive autonomy model for both the hills and valley at the ground level, to be united under the larger administrative umbrella of the state at a higher level.

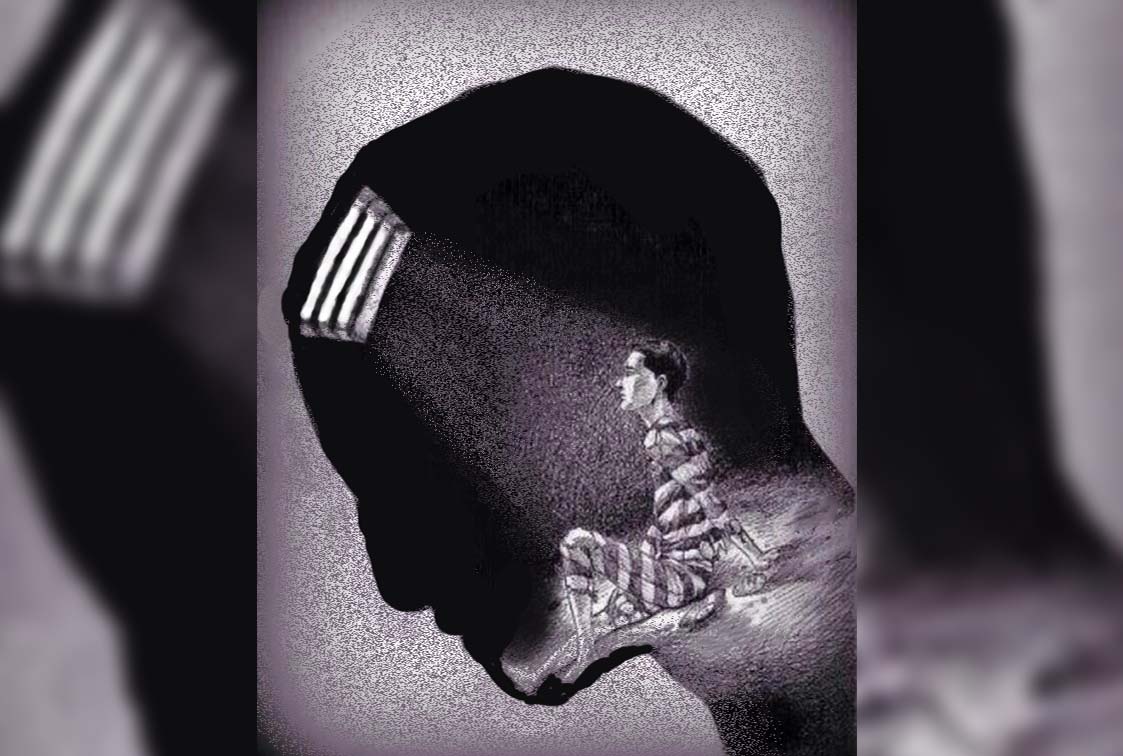

What has also become more than evident in the charges and counter-charges provoked by these latest allegations of gross policy discrimination based on which a push for a separate administration for the hill areas under the banner of a rushed “The Manipur (Hill Area) Autonomous District Council Bill 2021” was made, a matter still pending admission in the Assembly, is what has been acknowledged as a universal reality of a tendency of people to become prisoners of their own perspectives. This also came up in an indirect way in one of the discussions I participated in, organised by a group in New Delhi on the idea of public intellectuals and their importance in constructing the foundries in which social ideas are shaped and given life. One of the points of the discussions was on whether “public intellectuals” and “organic intellectuals” the same? The two are often confused and taken to mean the same, but Antonio Gramsci who coined the latter meant them to be quite different. “Organic intellectuals” are an extension of his notion of “common sense”, and he was suspicious of both as their foundations are rooted in the social environments they were born in. In an ethnically riven society such as Manipur, it is only natural for even “common sense”, and therefore “organic intellectuals” born out of them, to differ in outlooks, sometimes radically. This was seen even in the noisy contests for and against the HAC Bill 2021 case and the charges of endemic policy discrimination against the hills.

For the valley, this perspective prison is about the absoluteness of a history of Manipur they uphold and its supposed infallibility. All policies of the state of Manipur must first see this history as sacrosanct, disregarding in the process the universal truth that history is not something static or frozen and is instead a perpetually progressing phenomenon, therefore the need to refresh and reinvent its domain both in physical as well as psychological terms periodically. On the other hand, for those who live in the hills, any territory that has a higher altitude than the central Imphal Valley, must be considered hill, therefore come under their exclusive proprietorship. Never mind Imphal Valley itself is at an altitude of 780 meters above sea level and that other valleys such as the Leimatak Basin of which Khoupum Valley is a part, is at a lower altitude than Imphal Valley, a topographical fact which made engineers conceive of the idea of a Loktak Downstream Project. By this “common sense” and “organic intellectualism” again, in deciding the belongingness of hill territories, those who live on top must be privileged over those who live at the foot even when the territory in between are completely uninhabited. This modern demarcation of hills and valley in Manipur is a direct inheritance from the British days when revenue and non-revenue lands came to be classified differently as they had done in Assam with the drawing of the Inner Line by the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation of 1873. Otherwise, if commonalities in legends and folklores of all were to be taken as the parameters, community domains were defined very differently and overlapped considerably. From personal experience I know, even as late as the 1970s and 1980s, people as far away as Wangkhei very much considered Nongmaijing hills as also their domain (not exclusive) and went there for firewood and herbs collection daily. It was also the favourite picnic destination for youngsters from the area.

“Organic intellectualism” and its hegemonic grip over traditional pubic spheres is therefore what must be first overcome, and in its place another intellectual tradition that takes into account the unfolding reality in the objective world, and the needs of the times in a rational and humane fashion, must be instituted. Manipur and its communities, and indeed this would apply to the entire Northeast region as well, must free themselves of their respective prisons of hegemonistic perspectives and strive to see the world beyond where a more comprehensive and rational unity, beneficial to all in an equitable way can be hopefully worked out. The state and its communities must be ready to scramble whatever have become redundant of its past, and from it rebuild a present and future in which all can have just and equitable stakes. Let everybody keep in mind what so many scholars and statesmen beginning from Halford Mackinder in the early 20th Century have cautioned, that certain geographies are integral and any attempts to separate what are integral can only lead to violence and mutual misery. In common parlance, this emancipation from the prisons of perspective is also often referred to as “thinking out of the box”.