The name Kabaw has baffled writers and researchers of Manipur and Myanmar for a long time. There is no such meaning of the name Kabaw found in Manipuri dictionary. After in-depth research and corroborating with renowned Tai/Shan author and researcher Dr. Sai San Aik, 80 years old, of Yangon, Myanmar the name Kabaw is indeed derived from the word Kambosa/Kambawsa which is a Pali name for Shan State i.e. Kambosa=Kubo→Kambawsa=Kabaw. The place names Kambosa/Kambawsa for Cambodia were given by the Brahmans who worked in Royal Courts there. The ancient name of Cambodia is Kampuchea derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Kambuja’ meaning “The land of peace & prosperity”.

The Tai/Shan connection with Cambodia is known from the account of Joseph E. Schwartzberg’s “The History of Cartography”, vol. 2, book two, 1994, in his Southeast Asian Geographical Maps stated the term “Shan” appears to be used here as a generic designation for host of non-Burman peoples, including the Kasi Shan (west of whom lie the Kasis or Manipuris), Lowa Shan, Tarout Shan, Jun Shan (with their capital at Zaenmae, or Chiang Mai), Judara (Ayutthaya) Country (Siam proper), and Lanzen Shan (Laos), East of these are the Country of Judara Shan (Cambodia, which was then tributary to Siam) and the Country of the Kiokachin Shan (Cochin China), within which the Wild Lawa Hills, a perplexing toponym, suggest the Annamite Cordillera.

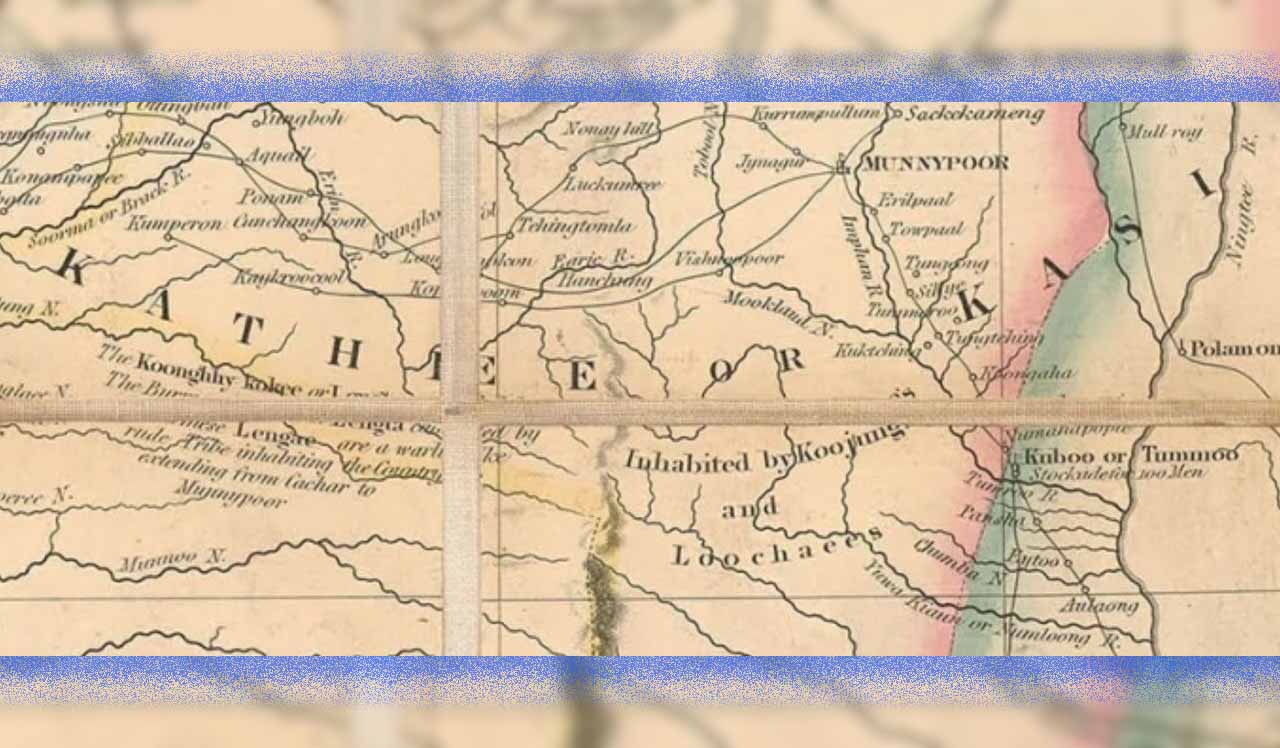

Ningthee River written as Ningtee R. (Chindwin River) is depicted on “A Map of the Burmese Empire” drawn by cartographer James Wyld in 1886, a folding map of Burma based on documents from Surveyor General Office of India, published after the Third Anglo-Burmese war 1885 with drawing of Kathee or Kasi (Manipur written as Munnypoor) on the map. The map also shows Kabaw Valley areas inhabited by the Kathee Shan and the Mrelap Shan (Shanni).

Dr. Sai San Aik states that Shanni origin is Tai/Shan. In the 1921 Census of India (Burma Region) Myitkyina+Kartsa, the total Shan population was 224734 and only 110163 spoke Tai. In the 1931 Census of India the Shan population was 121109 and only 71747 spoke Tai and slowly Tai Leng word was translated to Burmese Shan-Bamar. In need of a (Shan Special Region) totally different word Shanni was used politically which could be about before or after 2005. The Special Regions were offered to Wa/Pa-O. Upper Burma wanted one too but the Central Government was clear if one ethnic if they have got one State/Region i.e. Tai/Shan got Shan State, cannot have a second and for this very reason the Upper Burma Tai-Leng took up seemingly different name Shanni (The Burmese translation of Tai Leng).

At present Shanni roughly have a population of 4 million people living in Sagaing Region and Kachin State of Myanmar and its militant outfit Shanni Nationalities Army (SNA) is allied with Junta to fight Kachin Independent Army (KIA) and KNA (B) with the ultimate objective of getting Shanni Statehood for its inhabitants carved from Kachin State and Sagaing Region.

Major Simon Fraser Hannay in his book “Sketch of the Singphos, or the Kakhyens of Burmah”, 1847, recorded at a very early period the Shans of Yunnan extended their conquests to the country immediately West of that Province and when in future ages Yunnan came under the dominion of the Tartar dynasty of China, Moonkong or Moong Khao Loung, the present Mogaung of Burmah, was the seat of a powerful Shan kingdom, whose dominion extended from the 23° to the 28° of North Latitude and who overran Assam, founding the present Ahom dynasty of the Burrumpooter valley, and likewise established their power and dominion in the country West of the Kyendwen river including the valley of Munneepoor, the inhabitants of which are to this day called Cathay Shans.

Dr. Sai San Aik also stated the Shan people in Myanmar called themselves as Tai, the Ayutthaya of Thailand (derived from Sanskrit name Ayodhya) called themselves as Siam, Jun/Yuan/Zaenmai and the Burmese wrote Siam but pronounced it as Shan because they have no word ending in M. Burmese pronounces Sanskrit (Sa) and (Ra) as (Tha, Ta) & (Ya) and this is the reason why Burmese called Manipuri Meitei people Kathe/Kathe Shan and Tai/Shan called it Kassay/Kassay Shan.

The Khamti Shan knows the Meitei people as “Katai” or “Kathai”. The meaning behind this word is the race that broke away from wider Tai group and in the Tai Journal in new Shan script by Mahamung (Muse) “Tai in the World”, 2005, Meitei ethnic of Manipur is mentioned in the list as one of 83 Tai sub-tribes in the world known as “Tai Moy” or “Kassay”. Meitei ethnic belongs to Southwestern Tai people’s Northern branch. The Tai peoples are scattered in Northeastern States of India i.e. Upper Assam, Namsai and Lohit Districts of Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur Valley. They are also settled in five countries namely Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam and Yunnan Province of China with an approximate population of 100 million people.

Edward Harper Parker H.M. Consul, Kiungchow, Officiating Adviser on Chinese Affairs in Burma in his book, “Burma with Special Reference to her Relations with China”, 1893, states that Chinese have records of the existence of Manipurese people under the name Kie-sie, this last name being imitation of the word Casse or Cathay, meaning “Manipur-people.” The Chinese annals also mention Shan’s possession of the Manipur kingdom at different times, and for several centuries. The Manipur kingdom was influenced by Tai polity and was part of the Tai confederacy as one of the semi-independent Shan States in the kingdoms of Nanchao, Mong Mao Long and Mogaung.

The Manipuri people addressed the Tai/Shan people as Kubbo/Pong and are found in the writings of Ney Elias in his book “Introductory Sketch of the History of the Shans in Upper Burma and Western Yunnan”, Calcutta, 1876. He recorded the Tai/Shan is known to Manipuris as Kapo (Kubbo)/Pong. The use of word Pong by the Manipuri people meant Mao Shan/Tai Mao and the Manipuri people called themselves as Moitei. The Siamese (Thai) knows Shan people as Yodia Shyan and the Burmese knows Tai/Shan people as Shan/Shyan.

According to renowned archaeologist Dr. Okram Kumar Singh the present-day Meitei population also exhibits the physical characters probably of the cross-breed of the prehistoric population, thereby suggesting the continuity of the prehistoric Stone Age people in a mixed form till the present.

Indigenous Meitei population is a mixed race and Tai/Shan ethnic is known as Chinese Dai (in China), Tai (in Myanmar and Northeast India) and Thai (in Thailand). In the racial composition of homogenous Meitei ethnic, Tai ethnic is one of the ethnic in the gene pools or ethnicity estimates of a Meitei in the scientific DNA test results shown in the most Meitei individuals i.e. AncestryDNA and 23andMe DNA genetic testing for Ancestry currently regarded the two most popular tests of Ancestry DNA in the United States.

The earliest official account of Tai/Shan settlements in Kabaw Valley in BCE is mentioned in Burmese chronicle namely the ‘Yazagyo’ or ‘Kale’ chronicle. G.E.R. Grant Brown, I.C.S., in “Burma Gazetteer Upper Chindwin District”, 1913, recorded Yazagyo chronicle is of unknown origin, embodying this legend, is in the district office. It contains a list of princes in which Indian names give way to Shan as early as 210 B.C., when the kingdom is said to have been united by marriage with that of Mohnyin (Katha district) in the person of Saw Kan Twe, son of Kumonda Raja by the daughter of the Mohnyin prince.

The research journal by Myanmar Historical Commission, Yangon vice-chairman Dr. Sai Aung Tun titled “The Tai Ethnic Migration and Settlements in Myanmar”, 2001, recorded in 600 CE the Tai ethnic migrated to Upper Myanmar, Manipur and Assam during the formation of Shan States in Myanmar and the major wave of Tai ethnic migration from Yunnan happened in the reign of Sao Hsam Long Hpa (Samlungpha) which continued till 1400 CE. The Tai peoples were the cultivators of wet rice known as ‘Na” culture and brought the technology to Southeast Asia from Yunnan.

Maurya is the ancient name of Kabaw Valley recorded in the writings of Lieut.-General Sir Arthur P. Phayre, G.C.M.G., K.C.S.I., and C.B. in his book “History of Burma”, London, 1883 as follows:

Sir Arthur P. Phayre mentioned Indian princes spoke Sanskrit may be most reasonably assumed, although the latest compiled records have come to us in a Pali form. He also stated the route by which the Kshatriya princes arrived is indicated in the traditions as being through Manipur, which lies within the basin of the Irawadi. The northern part of the Kubo valley, which is direct route from Manipur towards Burma, is still called Mauriya or Maurira, said to be the name of the tribe to which King Asoka belonged.

Sir Arthur P. Phayre in his write up “On the History of the Burmah Race: Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London”, Vol. V, New Series, p. 25, 1867, recorded the Burmese called the territory, west of the Chindwin, Kabaw valley, as Mau-reya, Mau-ringa or Mwe-yeng.

Dr. Sai San Aik in his book “Basic History of Multiracial Burma 1980: Indianization and Burmanization”, 2015, recorded the word Maurya is derived from Hindu name and in Pali Maurya is called Mweyin.

Colonel G.E. Gerini in his book, “Researches on Ptolemy’s Geography of Eastern Asia (Further India and Indo-Malay Archipelago”, London, 1909, p. 745), says ‘According to Burmese Royal Chronicle (“Maharajavamsa”) Dhajaraja, a king of the Sakya race, settled at Manipura, about 550 B.C., and later on conquered Tagaung (Old or Upper Pagan)’.

Sir Arthur P. Phayre further recorded Daza Raja ruled both the kingdoms of Mauroya and Tagaung simultaneously and sixteen of his descendants were said to have reigned. After the reign of those sixteen kings in the two kingdoms, conflicts in the reigning family and eventful invasion of the Shans brought about the dissolution of this realm.

Rajagrha, commonly Yazagyo, village exists also in West Burma in the Kale township and Upper Chindwin district. The “Upper Burma Gazetteer” Part II, vol. III, p. 393, speaks of it as having been “the ancient capital of almost forgotten kings, as it was in more recent years of the Sawbwa.” Rajagrha is a name, however, applied to Kassay (Kaseh, i.e. Manipur). The name Yazagyo is itself no doubt a corruption of Rajagriha, the residence of Buddha and capital of the ancient Magadha.

The name Kassay for Manipur is found in the writings of Jacques P. Leider. He recorded the Burmese called Manipur “Kassay” and the Burmese Royal book Lokabyuha-kyam mentioned the name “Manipura” was only adopted when a faction of the Manipuri court openly favoured the changes promoted by the immigrant Bengal Brahmin in 1742 CE.

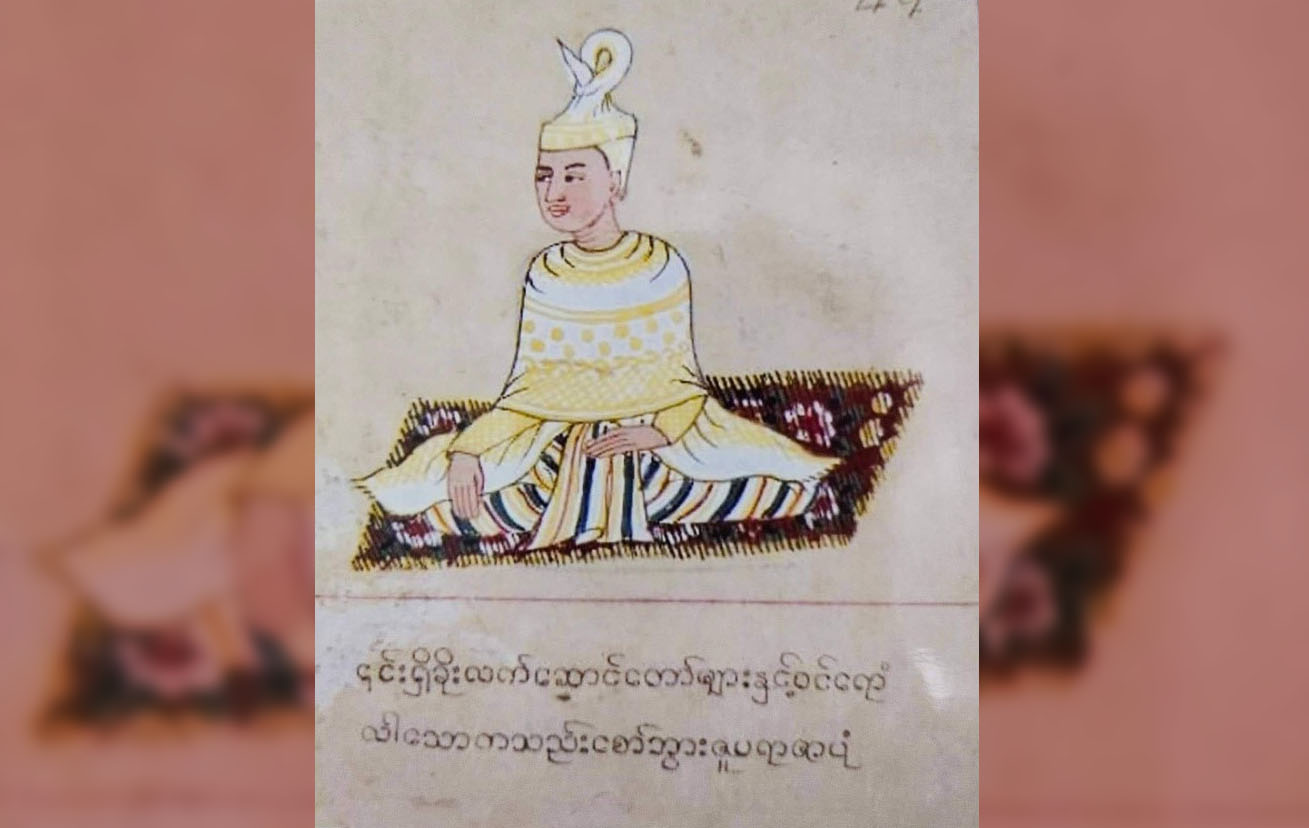

P.E. Maung Tin in “The Glass Palace Chronicle of the Kings of Burma”, 1921, recorded the Sakiyan king Dhaja Raja first founded and reigned in Moriya. The Raja assumed the title of Thado Jambudipa Dhaja Raja. The name Moriya occurs in religious books such as the Commentary on the Dhammapada; in secular works such as Gotamapurana, it is called Moranga, and Mawrin in the Arakan Chronicles; now it is Mwerin.

The mention of Sakya/Maurya race belonging to mongoloid stock is recorded in Roger Bischoff’s book “Buddhism in Myanmar: A Short History”. He writes, “Some degree of migration from India to the region of Tagaung and Mogok in Upper Myanmar had taken place through Assam and later through Manipur. A tradition of Myanmar says that Tagaung was founded by Abhiraja, a prince of the Sakyans (the tribe of the Buddha), who had migrated to upper Myanmar from Nepal in the ninth century BCE. The city was subsequently conquered by the Chinese in approximately 600 BCE, and Pagan and Prome were founded by refugees fleeing southward. In fact, some historians believe that, like the Myanmar, the Sakyans were a Mongolian rather than an Indo-Aryan race, and that the Buddha’s clansmen were derived from Mongolian stock.”

Colonel G.E. Gerini further recorded the Mauryas belonged to Sakyan race. Every subsequent dynasty that reigned in Burma claimed descent from the Mauryas or Mayuras through the princes who founded Tagong and Old Pagan; hence the Burmese kings placed the peacock (Mayura) on their coat-of-arms, and this bird became the national emblem of the country Burma.

The mention of location of Yazagyo or Rajgriha at Kabaw Valley, the ancient capital of Kassay (Manipur) and Chin occupation of Kabaw Valley from Shan is recorded in the book “Buddha’s life in Konbaung period bronzes from Yazagyo”, 2018, jointly authored by Bob Hudson, Pamela Gutman and Win Maung. The authors recorded Yazagyo is located at Kabaw Valley, in a remote area of Northwestern Myanmar/Burma. The valley lies between the Upper Chindwin River and the hills which separate Burma from Manipur. Yazagyo is on a side road from the Myanmar-India Friendship Highway, 35 kms north of Kalaymyo. In the latter half of the 19th century, the Kabaw Valley was becoming depopulated due to attacks by Chin tribesmen. Some villages were destroyed and others were abandoned, their residents moving to larger centers for protection.

John G.R. Forlong in “Encyclopaedia of Religions”, Volume 3, New York, 1906, recorded from the time of Dhaja Raja down to the 11th century successive waves of Indian migration passed into the valley of Irawadi, bringing Sanskrit letters, legends, religions, and civilizations. It is an undeniable fact that Kabaw Valley belonged to the ancestral territory of Manipur (Kassay) from the time of Sakya/Maurya ruler Dhaja Raja 550 BCE.

The relevant accounts of the areas consisting of Kabaw Valley in Myanmar are given below as follows;

Gazetteer G.E.R. Grant Brown in “Burma Gazetteer Upper Chindwin District”, 1913, recorded the greater part of Kabaw Valley consists of Tamu Township, measuring 540 square miles, the remainder being in Thaungthut State with the mountain range to the east, which has been formed into forest reserves. The valley is wide, level, and fertile, but very little cultivated owing to its unhealthiness and to the difficulty of getting paddy to market. The only outlet is the Yu River, which is barely navigable except for a short time in the cold season and dangerous in the rains. By the time the paddy reaches the Chindwin its price is more than doubled. Many of the people still speak Shan as their mother-tongue, but Burmese is understood and in some cases Manipuri also. In certain villages Shan seems never to have been spoken, the language preceding Burmese having been Ingye or Kadu. Nearly all the inhabitants of the township are cultivators. Very little is to be seen of the trade which might be expected to exist with Manipur. Such traders as there are, come from over the frontier, and bring their wares on their backs to the Yu or the Chindwin.

The Kale Township of Kale sub-division on the north is continuous with the Kabaw valley (Tamu Township and Thaungthut State), and Shan is understood by the old people, though not now spoken. In the south it forms part of one long valley with the Yaw country (Gangaw and other townships of Pakokku district), and the villagers as far north as Indian speak the Yaw dialect. Outside Kalemyo nearly all are agriculturists.

Gazetteer J. George Scott in “Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States”, Rangoon, 1900, recorded the population of the Ka-le township consists of Shans to the north, Shans and Burmans in the centre, and a mixture of Yaws and Shans to the south. Originally the whole country was inhabited by Shans of the same race as the Shans of Hkamti and Hsawng Hsup (Thaungthwut). Of late years, however, the Burman element has been introduced by immigration from Burma via the Chindwin River and Ka-le-wa, and a strong contingent of Yaws from Yawdwin, Pauk, and Gangaw settled in the valley on the accession of Po Kan U, the first Sawbwa, to power. To such an extent have outside influences (notably Burmese) prevailed of late years that the Shan is no longer a predominant nationality in the valley, and their language is also fast losing ground, except in the extreme northy of the valley near Yaza-gyo, which from its secluded position is least exposed to contact with the outer world.

The following accounts of G.E.R. Grant Brown given below is of utmost importance to know the areas consisting of Kabaw Valley. He recorded the town-ships of the Kubo valley subdivision were called Witok and Tamu. In 1891 the Kale State became the Kale township, and formed with the Kabaw valley the Kale-Kabaw subdivision. In 1897 the Kabaw (now Tamu) township was transferred from Kale to Kindat, and the Balet township from Kindat to Kale. In 1905 the name of the northern subdivision was changed from Legayaing to Homalin, and Kabaw to Tamu township.

To the north of Kale is Thaungthut State, A Shan State lying between Manipur and the Chindwin. Northwards the boundaries have not been defined. The Nampanga River has sometimes been regarded as the northern boundary. The Shans and Burmese are plain-dwellers, and rarely give names even of the mountains which they see every day. Accordingly, there is no name in Burma for this range, but the Manipuris call it the Angaw Ching, or Angaw Mountains. To the west of this range is the upper part of the Kabaw valley, broad and fertile but sparsely populated and bearing a terrible reputation for fever among the dwellers in the mountains of Manipur, though it does not appear to be more unhealthy than most of the Homalin subdivision.

Thaungthut also claims to have had rulers since the time of Buddha, but its history is even more legendary. Up to the reign of Anawrata (1010–1052 A.D.) it is said to have been an independent kingdom with its capital at Gawmonna, near the site marked on the map in 24°31´N. 95°34´E., as “Thap or Old Samjok,” Samjok being the Manipuri form of Thaungthut. Anawrata is said to have appointed a Burmese Governor with the title of Thokyibwa. During the reign of Tarokpyemin in the thirteenth century, when the Burmese kingdom lost many of its outposts, it was subdued by the Manipuris, and it seems to have paid tribute to Manipur until the conquest of that State by Alaungpaya (1753–1760).

The G.E.R. Grant Brown account gave clinching historical evidence to Manipur’s occupation of Thaungthut (Samjok) in the 13th century until Alaungpaya, the founder of Konbaung Dynasty wrested control of Thaungthut from Manipur in the second half of the 18th century.

According to Captain Grant with reference to his letter dated 5th February 1827, Gumbheer Singh’s Levy to Tucker, Commissioner, Sylhet, Correspondence Letters between Fort William and Governor General on the North East Frontier, 1827, R-1/S-B/140, MSA the Samjok Rajah and the Kule Rajah were inhabitants and descendants of the ancient Rajah of Manipur. The mother of the Kule Rajah was a native of Manipur.

Myanmar scholar Thin Thin Aye in her article titled, “The Significant Feature of the North-West Myanmar in the Konbaung Period”, recorded the territories located in the north-west Myanmar were in a state of unrest owing to the invasions of Kathe (Manipur). These territories were far away from the capital and were not easy to reach and the King’s administration was not felt. Kathe invaded Sagaing due to the lack of security in the far-flung territories of the kingdom. This was one of the major facts that Nyaungyan dynasty (restored Toungoo dynasty) was destroyed. In the reign of Mahadhamayazadipati in the Nyaungyan dynasty Manipuris had influenced over Kalay, Thaungdut, Tamu, Khampat in the north-west Myanmar. The jurisdictions of Thaungdut, Tamu and Kalay occasionally fell under Manipur control and sometimes under Myanmar control. Due to Manipur-Kathe invasions north-west Myanmar became restive.

Alaungmintaya marched to Manipur on 12 November 1758 and took over the country completely. That was the first conquests of Manipur by Myanmar in the Konbaung period. During his military march to Manipur, Alaungmintaya occupied Imphal at the north-west Myanmar. So also, Kabaw valley region was occupied. To defend the invading Kathe, Alaungmintaya placed at Tamu a sentry post under Setyaungbelu with over 500 gunners, and one at Thaungdut under Shwetaungoudain with over 500 gunners, as border guards. It was presumed that when Setyaungbelu passed away he became a nat. There is still a shrine of a nat at Tamu. At Tamu and Thaungdut were established permanent stockades. An inscription was set up.

After the first Anglo-Myanmar War concerning demarcation problems among the states cropped up. Myanmar officers wanted to get back the Kabaw valley which was once a territory of Myanmar. It was a narrow strip of land situated between Chindwin River and Manipur in the north-west Myanmar. By 1824, it was under the Myanmar. But English returned it to the Manipur Sawbwa when Myanmar was defeated in the First Anglo-Myanmar War. The Kabaw question was not entered in the Yandaboo Treaty. In 1830 the India Government decided that the valley should not be returned to Myanmar. Sagaing Min was very angry. But Major Henry Burney recommended its return. It is found that the north-west regions were peaceful after the Kabaw valley problem was solved.

The Konbaung period, Kalay, Khambat, Tamu, Thaungdut, Teinnyin, Razagyo at the north-west regions were peaceful and prosperous if Manipuris did not attack. The areas of north-west had been a political centre under the Myanmar kings and also a place of socio-economic importance and the spread of culture and Buddhism. During the Konbaung period Khambat and Thaungdut had been centre of the region for local administration. Moreover, these regions were important route for the Myanmar kings to march to their subordinate areas of Assam and Manipur.

Gazetteer G.E.R. Grant Brown had referred the version of Sir Alexander Mackenzie in their books who stated as such, “The Government of India considered it but just and proper that all the places and territory in the ancient country of Manipur, which were in possession of Gumbheer Sing at the date of the signing of the Treaty of Yandaboo, should belong to that Chief. The Sumjok and Kumbat divisions of the Kubo Valley, as far east as the Ningthee or Kyendwen River, were accordingly given to Manipur, and the Ningthee river formed the boundary between the two countries.”

The First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26) resulted in the bankruptcy of Bengal agency houses and cost the British East India Company its remaining privileges, including the monopoly of trade to China. The British Supreme Government had used Manipur’s Kabaw Valley, which was the inherently economic lifeline of Manipur along her ancestral boundary Chindwin (Ningthee) River as a bait for the sake of recovery of 1 million pounds sterling war indemnity in four installments. Tenasserim though desired by Burma was not handed over and the British after receiving the last war indemnity installment in 1833, treacherously transferred Kabaw Valley to Burma on 9 January 1834, the day Maharaja Gambhir Singh died of heart attack on hearing the sad news of Kabaw Valley transfer to Burma. For the loss of Kabaw Valley, the British Supreme Government paid 6,000 sicca rupees as an annual compensation every year to Manipur. The value of 16 sicca rupees in 1834 was equivalent to one gold mohur.

It is an open fact that kings of Manipur had approached the British Supreme Government so as to make retrocession of Kabaw Valley to Manipur when Upper Burma was conquered during the third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, but the British had ignored. At that time there was a proposal circulated in the Government of India whether the Kabaw Valley could be retroceded to Manipur.

During the reign of Maharaja Churachand Singh in 1932, the Manipur State Darbar submitted a representation of the Manipur State to the States Enquiry Committee for the retrocession of Kabaw Valley to Manipur, but it was ignored. A letter is retrieved from the sources of National Archive of India, written by Maharaja Bodh Chandra Singh, dated 2 August 1947, thirteen days before India got her independence from Britain, in the letter addressed to the then Viceroy and Governor General of India Maharaja Bodh Chandra Singh demanded retrocession of Kubo Valley to the Manipur State from Burma after the lapse of paramountcy.

After independence, during the period of constitutional monarchy of Manipur, M.K. Priya Brata Singh, the Chief Minister tried to correspond with the British Government on the issue. The Ministry of States of the Government of India under Home Minister, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel advised the state government not to pursue the matter; and the letter was returned. In fact, the British put the Kabaw Valley issue to notoriety and the complexity of the issue lingers till today for both Manipur (India) and Myanmar.

The retrocession of Kabaw Valley to Manipur State is an international issue and the Government of India should open the 190 years old colonial era Kabaw Valley transfer case and sincerely act and fulfil the return of Kabaw Valley to Manipur from Myanmar. It has been a long-cherished dream of every patriotic Manipuri citizen and it requires firm involvement of respective governments of India, Myanmar and Great Britain, as the later then British Supreme Government was responsible for the illegitimate transfer to Burma (now Myanmar) in 1834.

The writer is an independent researcher and author of “Vedic Imprint in Southeast Asia: With Special Reference to Manipur” and joint author of “The Political Monument: Footfalls of Manipuri History”. He is an MBA from Sydney, Australia and worked in Myanmar from (2013-16) in hydro and renewable energy space.